|

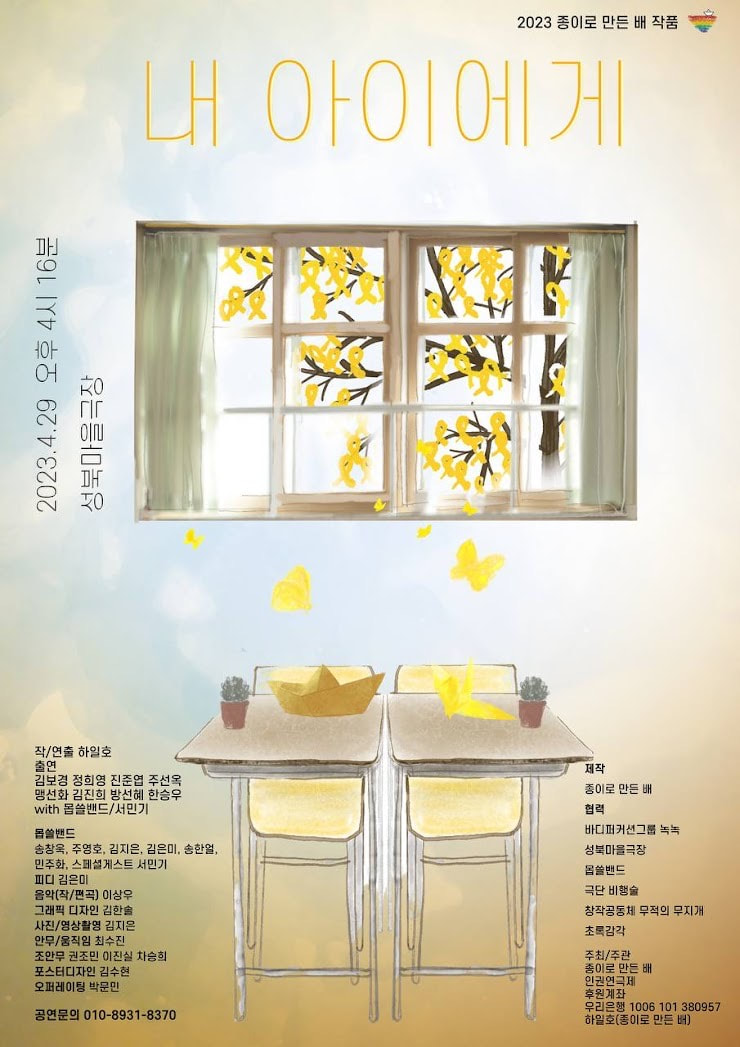

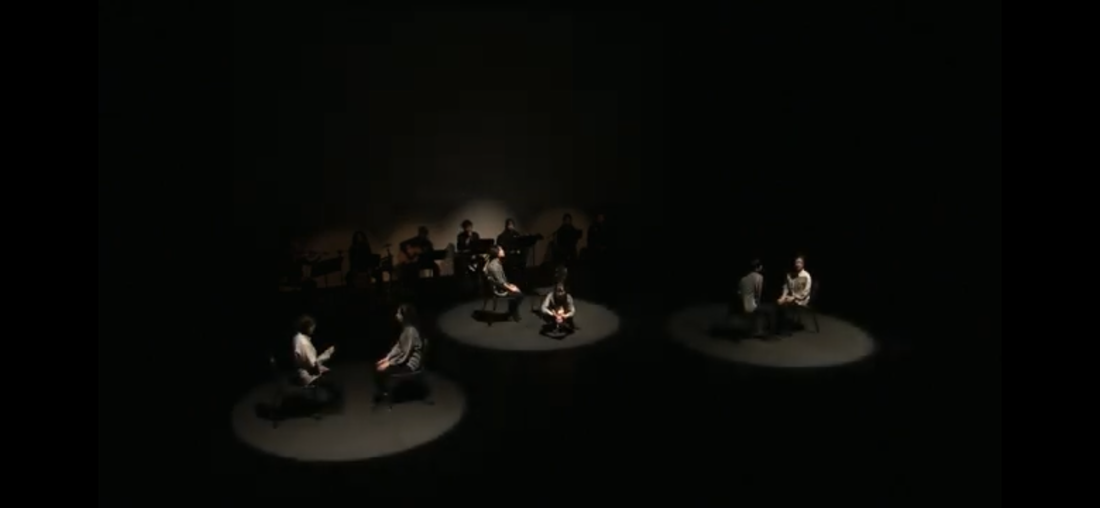

On the 15 and 16 April the theatre company “A Boat Made of Paper” toured “Calling You” in Ansan, South Korea. You can watch the full performance here. This is one of two productions that tour every year (the other being “To My Child”). It has been an annual excursion for those in the know in the years following the Sewol Disaster in 2014. More people should be ‘in the know’ however. Because even though it was a professional production Calling You was free. The theatre company asked for donations only. Deliberately situated in the city where most of the Sewol casualties came from it would seem churlish to do anything else. There was a clear goal of keeping the memory of the Sewol disaster alive but also creating meaningful linkages of solidarity to any places in the world were government neglect and corruption ride roughshod over human rights. The ‘calling you’ of the title then was directed at the audience as much as it was imitated in the cries of parents for their missing loved ones in the play itself. There was a sense of anger in a performance that measured the brutality of the uncaring state from the Korean War onwards. The needless deaths of casual workers in Seoul, and even massacres by South Korean troops in Vietnam, were positioned as one and the same. It was a ‘call to action’ as much as it was a ‘call to remember’. Memorialisation pitched as an ongoing process of curiosity and care running parallel with the grief and empathy more readily associated with it. There is much to say about the performance itself, but as mentioned above it was the broad character of the message that stood out. Calling You oscillated between intense portrayals of private grief and more considered attempts to communicate the complexity of this mourning to the audience spatially. The standout scene in this respect was ‘smell’. Here - backed by a talented band of musicians – the stage was arranged into tripartite spotlights each containing a parent of the victims staring at an empty chair and moving ever so slightly to the music in a minimal dance focused on the hands. As the lights went out the absences in front of these parents was suddenly filled with the form of their missing loved one. In one case this was a daughter who dances around her father with a little doll in her hands. Whilst in the others it was loved ones tentatively groping the air in gestures reconfirming absence rather than the hoped for connection. When the lights went out again left behind are only the traces or ‘smells’ of their children they began with. In the case of the doll this is something that is held to the chest of the actor and sniffed as the music fades out. For those in the theatre as well as tears the organization of the stage created a necessary sense of perspective. This spatial arrangement reinforced the sense of over 300 people who died on that ship and the shockwaves that still resonate on the streets of Ansan in 2023. Contemplating the grief of these three families in real time is difficult enough but multiplied by 100 it suddenly seemed impossible. This is a dramatic technique that speaks of the physical limits of empathy as much as it draws attention to the sense of injustice still burning in the hearts of those committed to understanding these events. This seemed pertinent. Only a week previously I had been invited to help maintain one of the Sewol memorials with a small group of activists. It was sad, but inevitable, to see an event that was once attended by many people in previous years, reduced to maybe seven of us included one mother and father directly affected by the tragedy. The weather-beaten memorial – even though it is not the only one in existence – now attests to a cultural memory paradoxically ‘draining itself’ in the words of WG Sebald of the stories that should sustain it. ‘Everything is constantly lapsing into oblivion’, wrote the author, ‘with every extinguished life’. The Sewol tragedy has not yet reached this level but the entropy that afflicts events like this threatens to shroud it in the nihilistic ‘so what’ and dismissive ‘move on’ that is a constituent part of the culture of immediacy and reaction that defines the present moment. What Calling You teaches us is that in every place and time it is our duty to develop communities of attention and care that of necessity go beyond this.

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

Categories

All

Archives

April 2023

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed