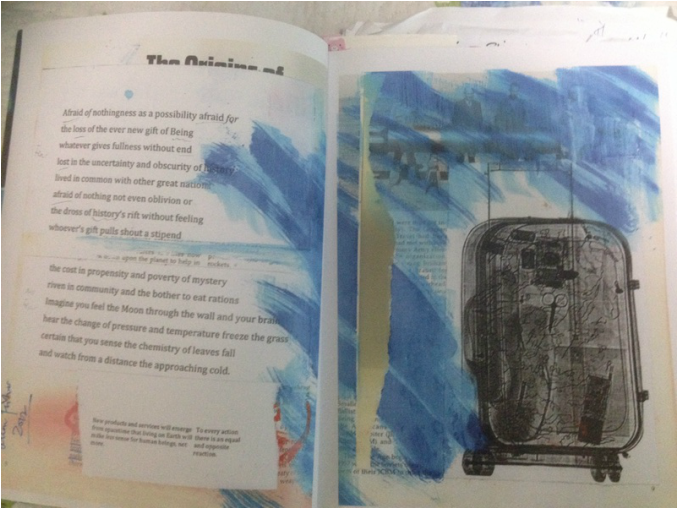

The "Human Anticipation" section of SPUTTOR The "Human Anticipation" section of SPUTTOR Read SPUTTOR (2) here SPUTTOR is a book. This may seem an obvious statement, but I want to reassert this central fact. Unlike Gravity (2005) or Proposals (2010), SPUTTOR retains aspects of Wilson’s text typical of narrative and expository forms. In that sense, to read SPUTTOR – taking it purely at face value – means to have a point of origin and a destination.[1] On page eight and nine of the text – as part of a section marked “human anticipation” – there is the image of a suitcase. For me, this also positions SPUTTOR as a journey. Like all journeys it begins with a sense of ‘anticipation’. But like all journeys there is a basic path or route set out from the very beginning. On this journey maybe a particular feature of the landscape will distract us. Maybe we will stop for a pint in that cozy looking pub. The basic trajectory of the route, however, remains set from the very beginning. Our ‘expectations’ pertain to the qualities of a preordained map. It is no accident, then, that poetry in its most recognizable sense emerges at this point in Fisher’s text. As mentioned previously, there are ‘forewords’, and ‘contents’ pages, as if Fisher’s intention is to produce a kind of ur-text humming constantly in the background. Wilson’s text is never forgotten, it burns its way through nearly every aspect of Fisher’s production. The ‘contents’ – as originally quoted in my first post – mark a journey beginning in ‘anticipation’ and ending in ‘loss’. This can be seen as the original narrative route explored in Wilson’s text, or even an echo of the dystopian path followed by Shelley’s ‘last man’. But, really, they are ‘anchors’, ways into a text that doesn’t really have the formal arrangement we expect. What matters is that these conventional aspects of Wilson’s Space Shuttle Story remain. ‘Prophecies’ are scattered by Fisher outside the entrance to his cave. ‘Take your time’, the poet demands in the guise of Sybil, ‘reassemble the leaves’. SPUTTOR, in this respect, doesn’t take us down a ‘canalized’ path. Fisher is playing with our expectations of what constitutes ‘literature’, he is presenting logically ordered material when in reality the content is the very opposite. Looking at pages eight and nine, for example, it is possible to see precisely how Fisher ‘teases’ our expectations as readers. The expectations imposed on Fisher’s own work via Wilson, are subject to further impositions from the conventions associated with the poet’s back catalogue. On these pages, for example, those familiar with Fisher’s work could be forgiven for thinking that what is being presented is the poetry, image and commentary format of Proposals (2010)[2]. Occupying the left hand page there are fragments of poetry, whilst on the right there is that image of a suitcase I mentioned previously. As in other works – although, noticeably, on the left hand page as opposed to the right – there is what can be assumed to be a prose commentary similar to Fisher’s last major text. It is as if the writer is providing ‘anchors’ to readers of his previous work that gesture towards how a reading of SPUTTOR might proceed. But it isn’t Fisher’s intention to present us with ‘more of the same’. This seems to be another way of, as Robert Sheppard has put it, ‘undermining’ the ‘logic and coherence’ of his core readership. Assuming that Fisher is still read intensively by those ‘400’ people he 'optimistically' mentioned to Clarke, it would be to deny the entire premise of his work if the same routes were offered towards grasping the material. This would be ‘perception’, as Fisher explained in the Forewords section, ‘without contingent comprehension’. The text primarily presents itself as a ‘damaged’ version of a previous text. Different aesthetic techniques are operating here, and the possibilities for interpretation are engendered in the play off between the form and message of Wilson’s original as well as the conventions of the poet’s own work. In my next post I will stay on pages eight and nine and examine Fisher’s text in terms of this ‘journey’ and ‘message’. [1] There is a lot to be said here on how ‘traps’ operate in Fisher’s work, something that I will explore in detail in future work. One thing that I love about SPUTTOR is how it invites readings by those unfamiliar with Fisher’s back catalogue. I would like these blog posts to be similarly ‘accessible’. [2] For more on this read Robert Sheppard’s excellent commentary on his blog here. Read SPUTTOR (1) here

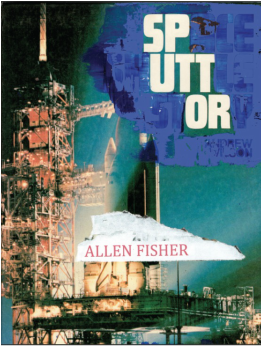

Even the page numbers of SPUTTOR mimic Wilson’s original. The book begins on page six and has a well-thumbed patina belying its origins at Hereford and Worcester Public Libraries. Wilson’s text is entirely accessible – part of a common cultural heritage – and remains as a linguistic trace echoing throughout the piece. The formal qualities of the original are 'damaged' enough to remain as a skeleton still informing the text. The foreword is a juxtaposition of miscellaneous fragments rather than the ruminations of an author. To Fisher, 'damage' suggests not only violence, but 'transformation' or the opportunities for 'another situation' (71). Wilson’s original ‘foreword’ is present, but this is subject to the intrusion of four other texts, which serve to question the original monograph in a variety of ways. There are actually two fragments by Wilson that make up Fisher’s introduction. The first screams jubilantly of a ‘bumper year for space achievements’, whilst the second has a more sombre tone. ‘This book tells the story of the Space Shuttle’, reads the second part, ‘tracing its history from before the Second World War up to the times of the disaster’. The timeline Wilson proposes – and the foregrounding of ‘disaster’ – means that the teleological account of the space mission must incorporate reports of its own failure. Not only is the mission identified as an unsuccessful project, but as an integral production of war. Technological advancement in modernity, and its relation to state power, are therefore persistent narratives operating in the background. The ‘achievements’ of the space mission are sullied by the inescapable knowledge of the conditions that spawned it. ‘The destruction of Challenger’, confirms Wilson, ‘has set the American Space Program back on its heels’. The original text presents two conflicting narratives that are wonderfully exploited by Fisher in his own version. The texts that cut across, and physically ‘damage’, Wilson’s original amount to the reorientation of an entire set of cultural values. The ‘new age’ roots of Place are reaffirmed in a quote from a website focusing on the ‘vibrational energies’ of the musician Daphne Oram, whilst a quotation from The Invisible Committee (2007) confirms a focus on a nomadic sensibility that has been a theme throughout his career. For the purposes of my own route into Fisher's poem, however, the most striking text comes at the bottom of the page. Here Fisher repeats a section from Mary Shelley’s The Last Man(1826). The original idea of a 'space mission', or 'getting off the earth', is transformed in this instance by the thematic concerns of Mary Shelley’s dystopian novel. This state-funded journey appears contextually as the beginning of the end. Unbeknownst to himself Wilson’s text is prophetic, it augments the originating point of decline. Wilson is Shelley’s ‘monarch of the waste’, a harbinger of catastrophe projected into the not too distant future (587). But there is a further resonance to this chosen passage that goes way beyond the emergent themes of ‘dystopia’ operating via Shelley’s text. The quotation itself draws on mythology – the ‘scant pages’ that the writer found in Sibyl’s cave – as if it gestures towards an approach to the reading process that is needed to encounter SPUTTOR itself. According to Virgil the Cumean Sybil wrote prophecies on Oak leaves assembled in order outside her cave. If the wind, or any other circumstances, happened to rearrange these prophecies then this infamous hermit would refuse to reassemble them. These ‘thin scant pages’ are precisely what Fisher presents us with in his latest ‘facture’. The ‘hasty selection’ of evidence by Shelley herself in the passage, is almost representative of the methodical process of selection involved in the reading of the poetry. Disasters, and fragments, are ultimately key to Fisher’s own ‘damaged’ material. It is up to the reader of these poems to reassemble the leaves. This brings to mind Fisher's 'optimistic' comments to Adrian Clarke that his poetry could expect an audience of '400' rather than '4000' (60). Shelley's reference to 'one of us' only understanding the prophecies, is almost analogous to the expectations Fisher has over the comprehension of his own readership. This is certainly not to suggest Fisher 'alienates' his audience, but rather that there is the need for the acculturation of a certain sensibility in an approach to reading his texts. In that sense, the foreword operates as a form of 'introduction'. This is not to 'introduce' the content as such, but to provide 'anchors' or let the audience know 'what [they]'re in for' as the poet has explained in the context of his live performances (79). This is part of a 'necessary difficulty' rather than an attempt to explain what the following text will be 'about'. The Cumean Sybil is an evocative parallel when considering such an attentive process. 'Anchors' are certainly present, but the onus is always on the 'inventive perception' of the audience. It is this knowledge that brings us to the final fragment of the forewords section in SPUTTOR. In a register that sounds strangely recognizable, a further statement is included that builds even more on this attitude to reading in the poem: "Our feelings of inconsistency or incoherence is simply the consequence of the foolish belief in the permanence of the self and of the little care we give to what makes us what we are. Reliance on perception without contingent comprehension perpetuates the state machine". The origins of this quote are impossible to identify, but a familiarity with Fisher’s prose points in the direction of his own works. By foolishly reading, by taking in what is only immediately presented, comprehension merely 'perpetuates the state machine'. The text never simply exists 'as is', but is dependent on factors beyond any effective attempts to control the material. By presenting Wilson's text in this way the narrative that occupies the original text is conceived as something much more complicated. The prospective audience is put through their paces early on in SPUTTOR, and the ground is set for a reading that revolutionizes the process of reading itself. This is an aesthetic entirely opposed to the ‘spoon feeding’ of audiences. As originally pitched in PROCYNCEL – Fisher’s earliest text – the poet and painter ‘emerges’ as a ‘member’ ‘of a progressive and progressively reactionary society willed to submission by a public that still considers instantaneous feeding, entertainment, art and satisfaction the truest road to their own particular heaven’ (7). Such an approach – which is only loosely considered by myself here (having left out the intersections of two other sources) – privileges a variety of possibilities over any single interpretation. Suffice to say, the traces of prophecy Fisher provides us with do not coalesce into a single vision, but are left open for interpretation through an engagement with the text. Allen Fisher's SPUTTOR arrived here last week. As poem, and image object, it is truly astounding. The quality of production makes Veer the perfect platform for its distribution. The entire piece is deftly inscribed and pasted over Andrew Wilson's Space Shuttle Story (1986), which was originally produced in celebration of the ill-fated Challenger space mission, or rather the history of technological advances that made it possible. This was a text that in its own words "trac[ed] the history of the Space Shuttle Program from the early days of rocketry to the destruction of the challenger in 1986". This makes it a strange book in reasoning and conception, as if there is an alternative narrative perpetually simmering in the background. As text and image, the original book traced a process that ended in failure. It has to be assumed that Space Shuttle Story was initially conceived as a celebration of the space race, with the disaster itself something of an afterthought. The idea of 'getting off the planet' and 'space orbits' - which Fisher defined as the main themes of the original text in an issue of Sugarmule - become something much more provocative and rich as a consequence. Language that was once complicit in the infrastructure of the state becomes a living entity subject to a variety of 'transformations'. The beauty of Fisher's work comes in how it reorients, and interferes, with that original text (or how he 'defamiliarizes' its content, to use a term more suited to his other recently reissued text from Veer). The sonorous adulation that defined that mission - coming as it did at the cold wars peak (all 'Red Dawn' and Reaganomics) - is rendered entirely suspect not just by Fisher's poetics but the tragedy that ended the mission itself. SPUTTOR is both SPUTnik and the hope of UTTerance: a stORy inclined to reveal and build on the original monologic narrative by means of the reader's participation and imagination. Alternative possibilities are allowed to emerge from within the tragedy of the dream. The text wonderfully merges the language of progress that defined that mission - as political project and eventual disaster - with alternative histories constantly weaving in and out of the mainframe. Like all of Fisher's work since the seventies the text examines 'where we are', in ways that would be impossible without poetry itself. These are poetic imaginings for a new age, that take into account not only political reality, but the immensity of our human condition. 'There are so many theories', as Anselm Kiefer would put it, '[but] all they describe is our lack of knowledge'. Fisher's text will be a focus of mine over the next few weeks as I try my best to come to terms with it via a series of investigations of both text, image and their intersections. I will begin this shortly with a look at the opening pages. This is an ongoing project, so a bibliography will be provided in my final post. For now I will simply reproduce the 'contents', which go some way to giving an initial glimpse of what is at stake: Human anticpation Human conditions Human health Human colloquium Human legacy 1 Human legacy 2 Human enterprise Human perception 1 Human perception 2 Human predation Human contradiction 1 & 2 Human contradiction 3 Human prospect Human substance Human cosmos Human understanding Human warmth Human loss Read SPUTTOR (2) here |

Categories

All

Archives

April 2023

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed