|

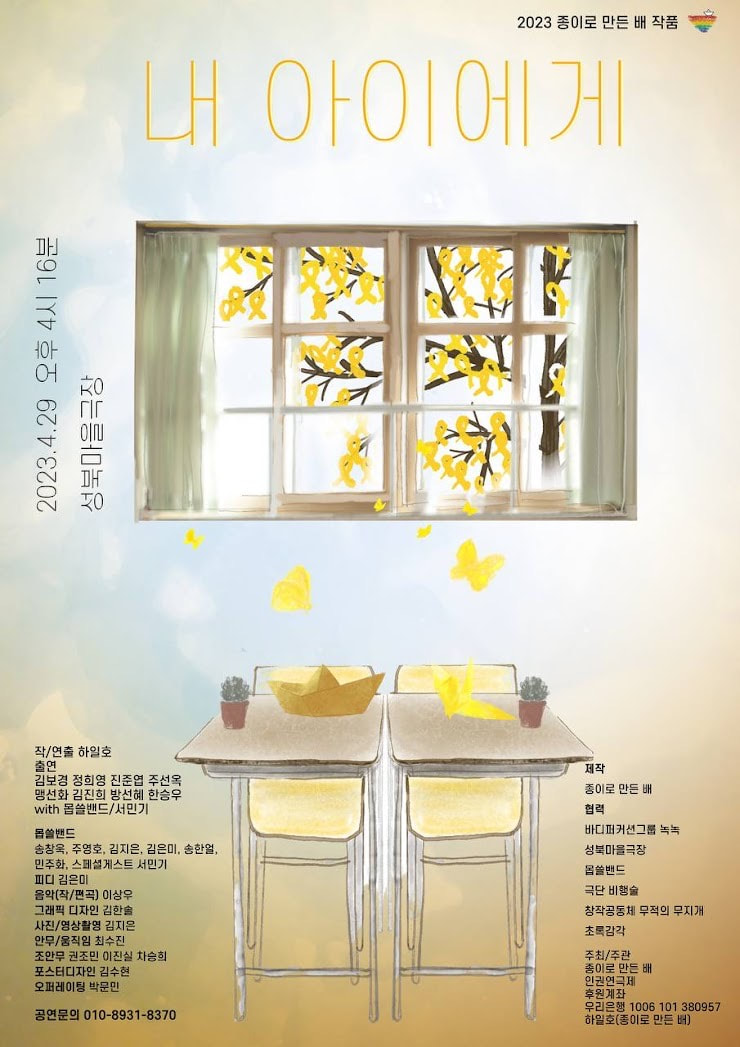

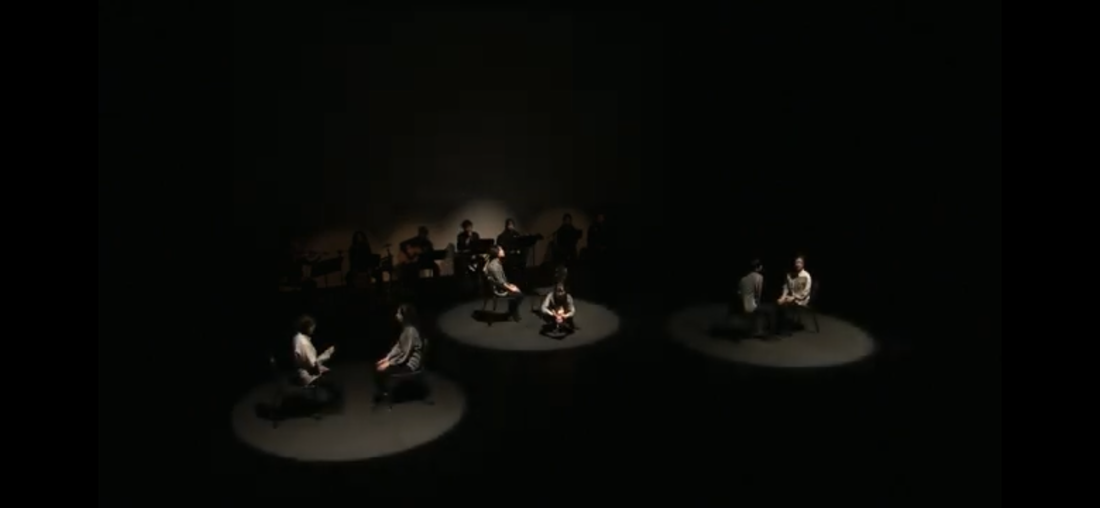

On the 15 and 16 April the theatre company “A Boat Made of Paper” toured “Calling You” in Ansan, South Korea. You can watch the full performance here. This is one of two productions that tour every year (the other being “To My Child”). It has been an annual excursion for those in the know in the years following the Sewol Disaster in 2014. More people should be ‘in the know’ however. Because even though it was a professional production Calling You was free. The theatre company asked for donations only. Deliberately situated in the city where most of the Sewol casualties came from it would seem churlish to do anything else. There was a clear goal of keeping the memory of the Sewol disaster alive but also creating meaningful linkages of solidarity to any places in the world were government neglect and corruption ride roughshod over human rights. The ‘calling you’ of the title then was directed at the audience as much as it was imitated in the cries of parents for their missing loved ones in the play itself. There was a sense of anger in a performance that measured the brutality of the uncaring state from the Korean War onwards. The needless deaths of casual workers in Seoul, and even massacres by South Korean troops in Vietnam, were positioned as one and the same. It was a ‘call to action’ as much as it was a ‘call to remember’. Memorialisation pitched as an ongoing process of curiosity and care running parallel with the grief and empathy more readily associated with it. There is much to say about the performance itself, but as mentioned above it was the broad character of the message that stood out. Calling You oscillated between intense portrayals of private grief and more considered attempts to communicate the complexity of this mourning to the audience spatially. The standout scene in this respect was ‘smell’. Here - backed by a talented band of musicians – the stage was arranged into tripartite spotlights each containing a parent of the victims staring at an empty chair and moving ever so slightly to the music in a minimal dance focused on the hands. As the lights went out the absences in front of these parents was suddenly filled with the form of their missing loved one. In one case this was a daughter who dances around her father with a little doll in her hands. Whilst in the others it was loved ones tentatively groping the air in gestures reconfirming absence rather than the hoped for connection. When the lights went out again left behind are only the traces or ‘smells’ of their children they began with. In the case of the doll this is something that is held to the chest of the actor and sniffed as the music fades out. For those in the theatre as well as tears the organization of the stage created a necessary sense of perspective. This spatial arrangement reinforced the sense of over 300 people who died on that ship and the shockwaves that still resonate on the streets of Ansan in 2023. Contemplating the grief of these three families in real time is difficult enough but multiplied by 100 it suddenly seemed impossible. This is a dramatic technique that speaks of the physical limits of empathy as much as it draws attention to the sense of injustice still burning in the hearts of those committed to understanding these events. This seemed pertinent. Only a week previously I had been invited to help maintain one of the Sewol memorials with a small group of activists. It was sad, but inevitable, to see an event that was once attended by many people in previous years, reduced to maybe seven of us included one mother and father directly affected by the tragedy. The weather-beaten memorial – even though it is not the only one in existence – now attests to a cultural memory paradoxically ‘draining itself’ in the words of WG Sebald of the stories that should sustain it. ‘Everything is constantly lapsing into oblivion’, wrote the author, ‘with every extinguished life’. The Sewol tragedy has not yet reached this level but the entropy that afflicts events like this threatens to shroud it in the nihilistic ‘so what’ and dismissive ‘move on’ that is a constituent part of the culture of immediacy and reaction that defines the present moment. What Calling You teaches us is that in every place and time it is our duty to develop communities of attention and care that of necessity go beyond this.

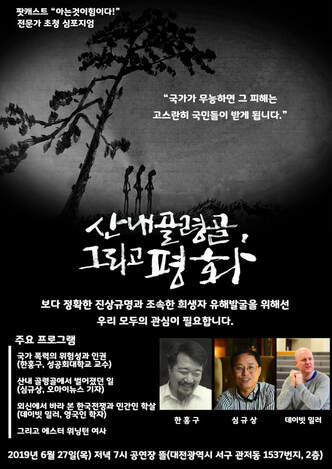

This is the trailer for a new KBS documentary premiering next week in South Korea. As an account of the massacre it focuses on Daejeon and the key stories that need to be considered when accessing the truth of what Winnington witnessed.

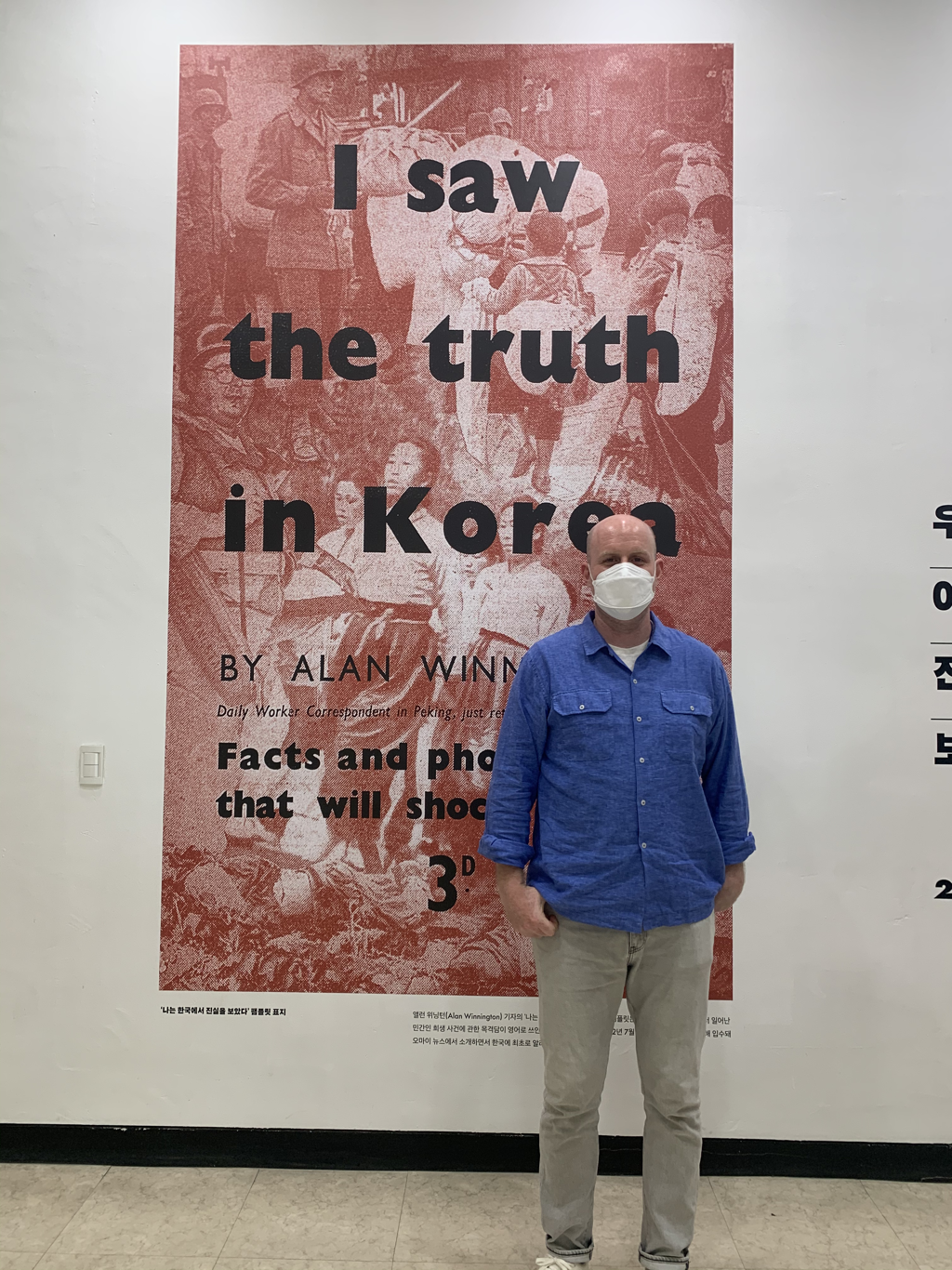

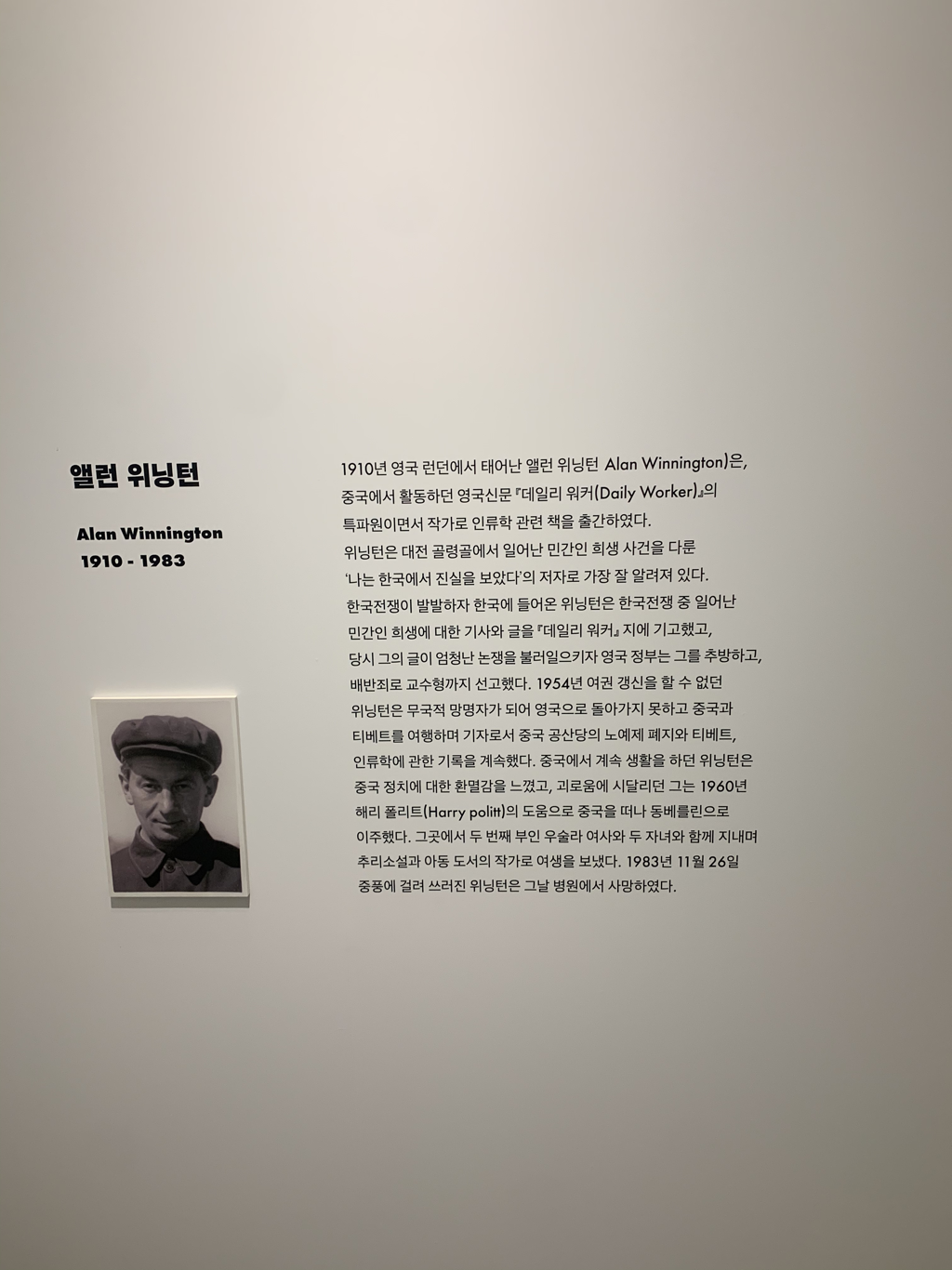

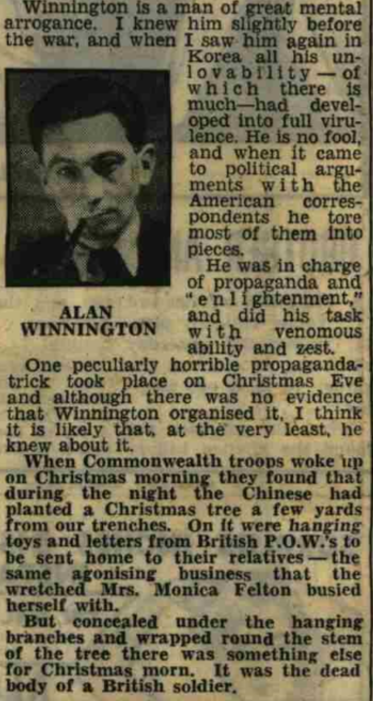

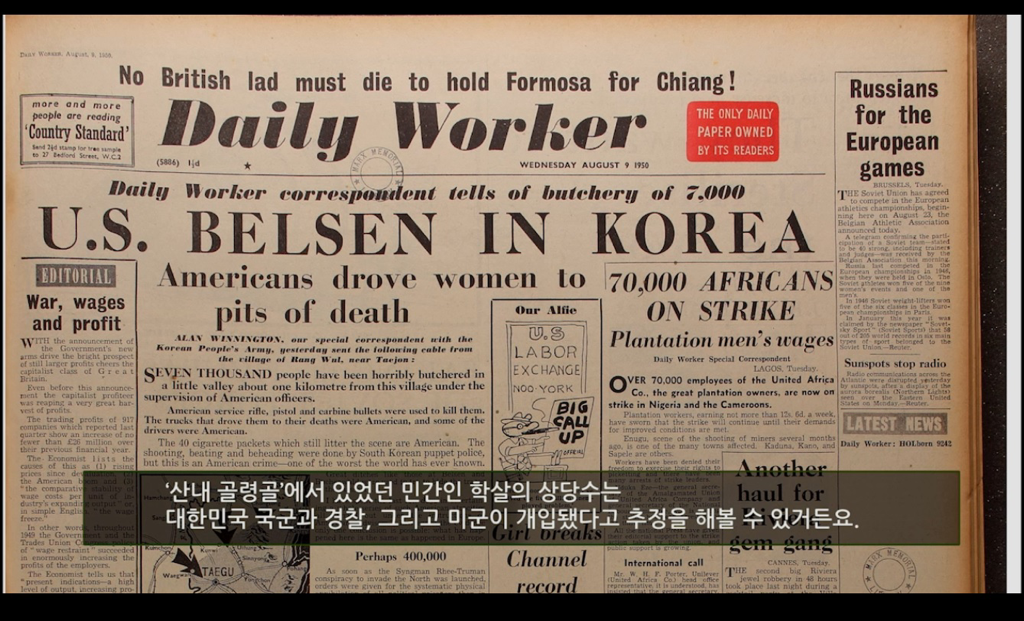

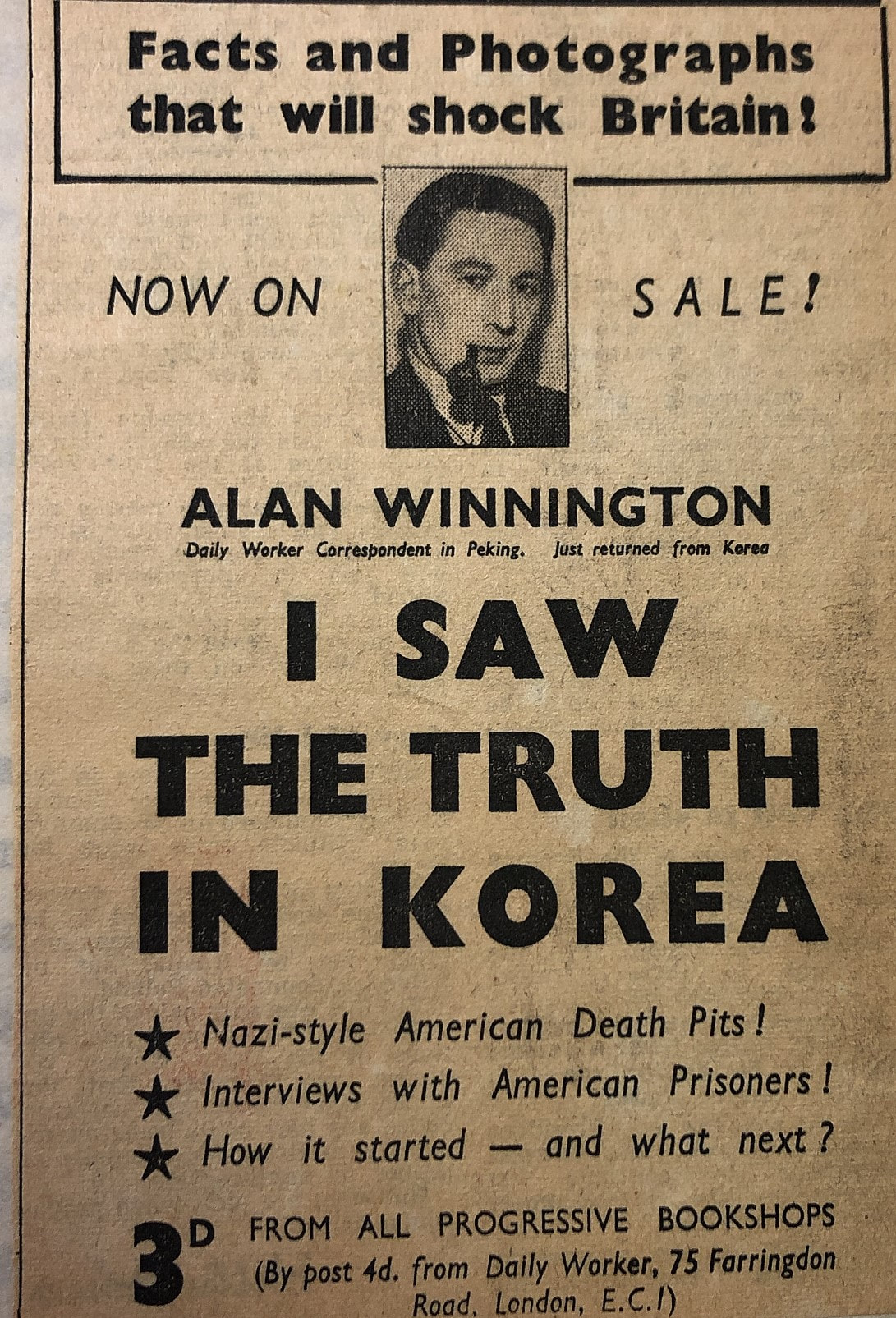

There is also a series of Newstapa documentaries focussing on these massacres at some point this year. Rather than just focussing on Daejeon these look at massacres throughout South Korea committed at the same time. I will definitely link to those in the future. One of these - in Gongju - is something I have been looking at in detail relatively recently. “Facts cannot be hidden forever... all we have to do is our share of getting the truth known” The above quote is taken from a letter from Winnington to the POW Andrew Condron in 1952. It still stands. So much is left over from the Korean War that is little understood or appreciated. This is why I wanted to be involved so much in this exhibition of Winnington’s photographs that opened today in Daejeon. It wouldn’t have been possible without the local council, and the amazing knowledge of local activists Shim Gyu Sang and Im Jaegeun. I could only contribute to the Winnington aspects of everything there. This was “my share”. I will continue to contribute for the same reasons wherever possible. Both because it is so necessary for a lasting peace in Korea. But also because Winnington himself is so misunderstood. Everyday there is new information that astounds me - and every day I am shocked by the consequences of what he witnessed. This excerpt from a “Cassandra” article in the Daily Mirror in 1955 is indicative when we consider the lies and misinformation that was spread around at the time. Not an attempt to “get the truth known” but to obscure it further. This is one of the main reasons we can only “s[ee] the truth” today. The exhibition will be open for ten days in Daejeon this week. At the 전통나래관 behind Daejeon Station (if anyone is reading this in Korea) I have been trying to write about the significance of Alan Winnington’s photographs for quite a while now. But due to copyright concerns and an evolving situation on the ground this hasn’t been possible.

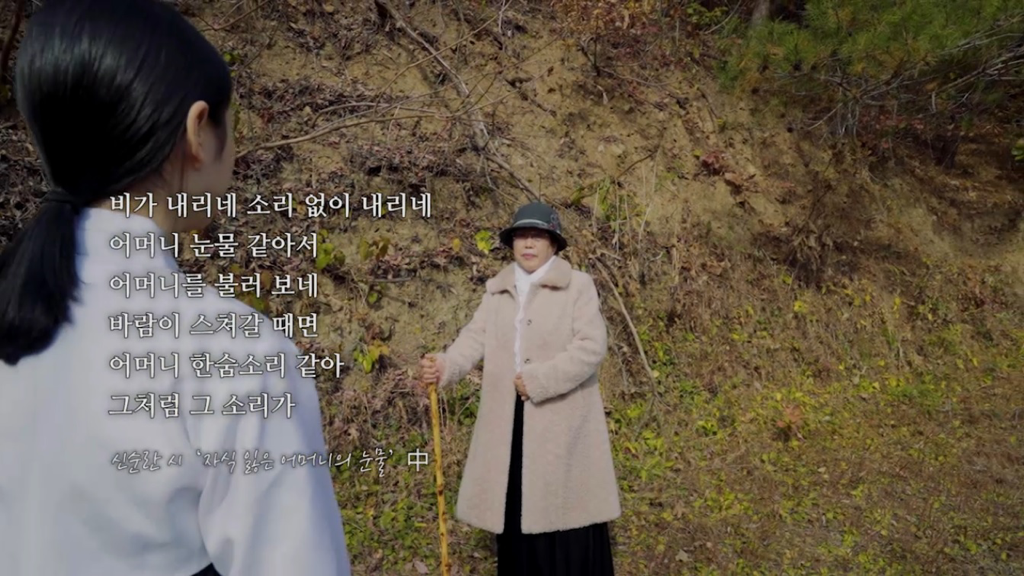

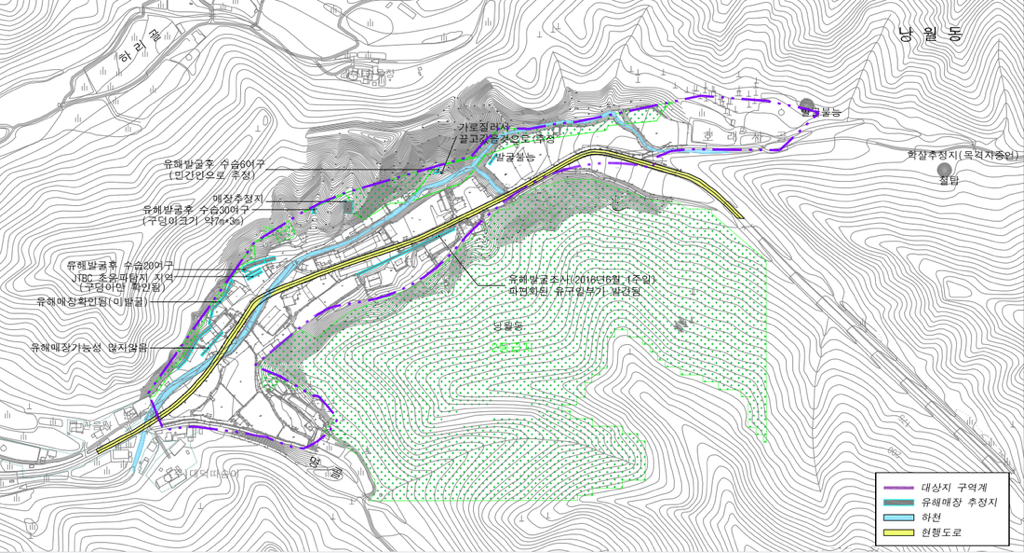

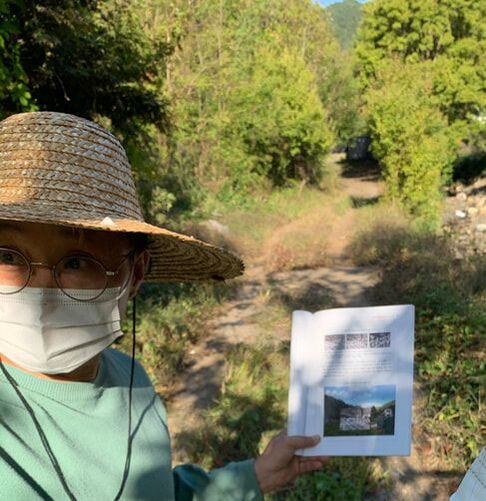

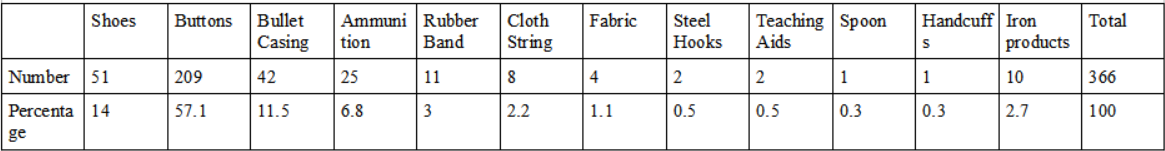

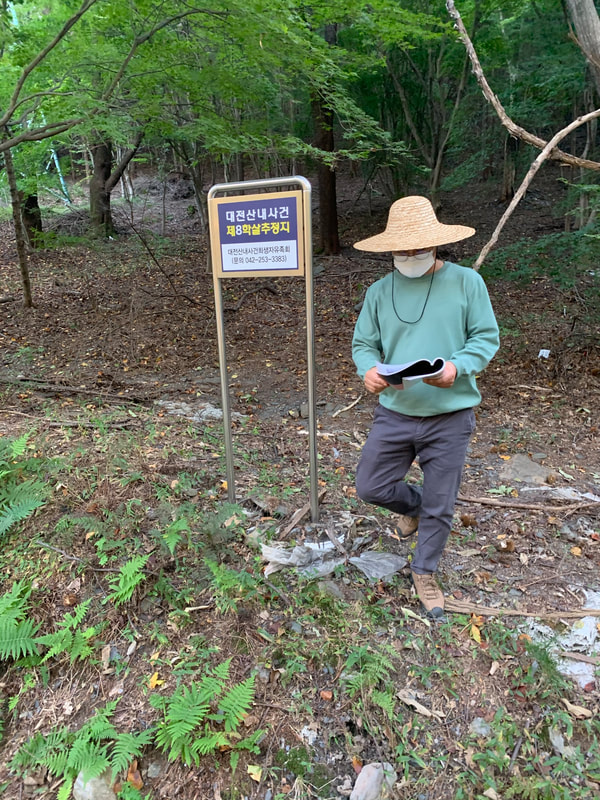

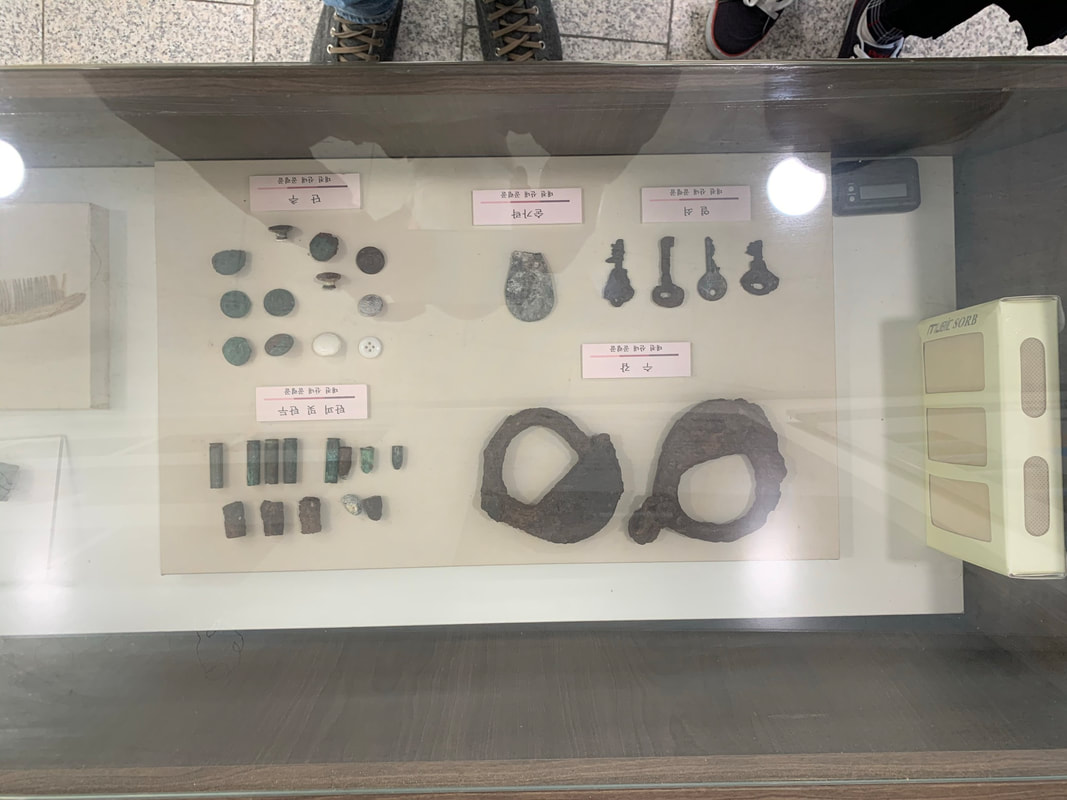

Thanks to History Workshop Online I was finally able to. https://www.historyworkshop.org.uk/radical-objects-alan-winningtons-camera-documenting-the-daejeon-massacre/ However please note that the archive is still uncatalogued at Sheffield. It will be open at some point this year (Covid allowing) No matter how hard he trieS, it’s impossible to forget. The trailer for the new film we have been working on about the Daejeon Massacre is now available. The title is 무저갱 (Mu jeo gaeng), and it follows the stories of the bereaved families as well as the excavations and my research on Winnington. The film bases itself on the story of a poem written by an orphan of the Korean War, and its journey into being made into a song by a composer and the poet’s granddaughter, In-between is the story of massacre itself, hauntingly rendered by an award winning South Korean animator. This week I am involved in the filming of a KBS documentary that will premiere during June in South Korea on the anniversary of the Korean War. I will also put up more details regarding this at a later date. Below is the trailer and a few screenshots from Abyss in the meantime. I’m hoping I can arrange a few screenings in the UK later this year. Let me know if you are interested on the contact page. In what follows I will recount a journey I made to the valley in Daejeon with the local journalist Shim Gyu Sang. I am making these posts to fill in the gaps for people who might be interested in the story of Alan Winnington, but also in the narrative that surrounds the Korean War in a much wider sense. Both are important because they are largely “inchoate” accounts that have accrued much complexity and misunderstandings over time. It makes sense to choose this particular word, because it is not that they are just “unfinished” but “unfufilled”. By which I mean these accounts lack context and closure. These posts are part of a collective attempt to truly understand what happened in the war and its aftermath. As a result they require attention to detail, and - as I've discovered recently - a spatial awareness that can evoke a sense of scale and experience. Similar things are true of Alan's “posthumous” autobiography published three years after his death. Both are narratives to which new information and context is constantly being added, and both are victim to prejudice and ignorance where the human element is rarely perceived in its full complexity. This is not about ideology, even if politics is inextricably bound up in what must be told. Instead these are stories about cruel cycles of history that care very little for political affiliation. As always it is people themselves who are disappeared in these partial attempts at retelling. So, again, I want to point to the “inchoate” status of these stories and events. At the moment it might be said that we are carefully assembling a mosaic, one of the most important parts of which is the oral histories that have been suppressed for so long. This comes with all the trauma these events still uncover, but also a curiosity at new discoveries. In the next few years I hope that this place, and the wider history surrounding it, genuinely promotes discussion. We have made much progress since looking into this in detail this year (most of which I will have to explain in the future), but every day brings new information it is hard to keep up with. At that level be aware that some of the things below may well be superseded in the future. We are continuing the excavations well into 2022 so this will inevitably be the case. In order to make this post I was taken on a tour of the site by Mr Shim in October. He is a genuinely inspiring person having written on this issue for over twenty years now. He has actually been following it for much longer, even when it wasn't safe to talk about it properly. Mr Shim is now an inextricable part of the discovery and reporting. His story is bound up with any goings on here along with those of another local journalist and academic Im Jaeguen. The enthusiasm and detail that Mr Shim provided me with during the exploration of the site was utterly boundless. His hospitality, and curiosity, are something I hope I can replicate albeit under much more favourable conditions. My mosquito scarred scalp and sunburnt body in October attested to the level of attention and effort that is still required to explore this site in full. I still smile when I think of Mr Shim squatting away snakes from site number three with a stick he had broken off a nearby tree. I hope that what is detailed below encourages more people to embark on a similar journey. Even if it is only with the information I have provided. The following, then, is a synopsis of the eight sites in the Daejeon Valley as they stand today. It must be remembered that these are only the ones that we know about. This does not mean that there aren't others. One of the most incredible things about dealing with Alan's primary sources is that the smallest detail can have huge implications for things on the ground in South Korea. Having seen primary sources by Winnington recently, as well as examining in detail his original reports, it is clear that much more could exist at this place that is simply unknown. All of the witnesses who lived here during the war have now passed on, and even Shim Gyu Sang had trouble getting them to explain their stories ten years ago. The only way it was possible – so he tells me – was to buy them makkolli and dinner and then drive them to the site where they would point through a closed car window at the mountain in the distance. This was out of a genuine, and completely understandable, fear of retribution by the authorities. I have included pictures of Mr Shim on our journey in the explanations. I should also mention that he soused me liberally in makkolli beforehand as well. Site One: Emmanuel ChurchThis is the site in Daejeon at which they are currently digging, although it will be extended to other areas in the future. Some recent discoveries confirm that people as young as fifteen were killed there, but also that (as Winnington stated in his original newspaper reports, and as has been confirmed since by witness testimony) many of them were women too. Both these facts are often omitted from official accounts, and it is important to restate them as often as possible. The distinctive aspect of site number one is the Emmanuel Church that exists on the site itself. Rather than being a longstanding construction it was actually built in 2001 illegally on land that should have been protected . This was simply an oversight by the local administration at the time, but it led to a protracted battle with the church that has only just ended through the compulsory purchase of the land. A lot of remains were discovered by the Bereaved Family Association as they stood by and watched outraged as the foundations were dug at the time. Shim Gyu Sang collected these in an old kimchi pot and buried them under the memorial stone that existed on site. At the moment of writing Park Sunju and his team have discovered 200 complete skeletons here, and this is only the very beginning of the process. In 2015 a test pit was completed where 20 bodies were found. After this excavation a raised earthwork was constructed on site in the shape that the pit is believed to follow, both as a memorial but also to point to the urgency of future diggings. It is at this place the final set of excavations will be ending this month. I am not sure it has been deemed wise to dig below the Emmanuel Church at the moment, but it is certainly being discussed as a possibility. Site Two: The Longest TombThis site is the one that gives the valley the name of The Longest Tomb in local mythology. In the two photos attached – I simply circled the camera from left to right where i was standing at the time – you can see the supposed extent (200 yards long according to Winnington) of the trench as it runs parallel with the new road built in the Sixties. It was thought to run from the pylon in the far distance to the house with the blue roof on the other side. New data, however, has shown us that this might not actually be the case. It seems that the residents of the valley confused the new road with the old one that existed at the time. I can't say much more about this at the moment, but the new excavations should be able to find the exact place of this trench due to the discovery of important photographic evidence This is the place where it was also assumed the construction company discovered a lot of remains when they were digging the road. Actually, Shim Gyu Sang traced this company a few years ago and they denied all knowledge of what went on at the time. It's only speculation, but it is most likely that rather than being “government interference” it was more to do with avoiding paperwork and delays to the project than anything else. But whatever happens, this place is a key area for excavations because of the size of the pit. Now that it has been located expect much more news in the future. Site Three: Truth and Reconciliation Commission ExcavationSite three is supposed to be the place where people in the collage made by Shim Gyu Sang earlier were killed after the two main massacre sites were filled in. This suggests that their killing was something of an afterthought, and they may have come from outside of Daejeon or were people who were captured further away. Because of the small size of this place it is quite unique. Apart from the identity of the people killed here lots of information has been found out. In fact, in the councils own list of excavations in the valley it is the only site that is labelled “done”. These days it is extremely inaccessible and is the place that Mr Shim used his stick to remove unwanted snakes and spiders. As can be seen from Mr Shim's demonstration below the way in which these people were killed was extremely methodical: All 29 of prisoners were forced to sit in an interlocking position in a trench and then buried were they fell. At the time of excavation in 2007 handcuffs, keys and various other things were found. You can see them in this post I made previously on the Sejeong Mausoleum. During this excavation enough items were found to prove that the people killed were prisoners as can be seen from the table I have included below:

This is the most inaccessible of the sites and in 2007 it was impossible to discover anything. The site is located on a forest trail in the mountain, and witness testimonies say that people were taken to this place from the second massacre site to be killed. There was nothing found by investigators in 2007, but it is said that there is indeed a small burial site by the stream where another excavation will take place in the future. At this place 5 people were found in an excavation in 2007, but Shim Gyu Sang is certain that there must be more. These people weren't prisoners as could be easily discerned at site 3 for example and what happened here seems to be most likely down to a personal or political grudge. Four of the people found here appear to be ordinary people but there is a curious aspect to one of the burials in as far as he is a high status person with leather bottomed shoes and expensive watch somewhere in his Forties buried much further away from the others. Also this person was not killed with an M1 cartridge like the other four, but a pistol instead. The main problem with excavations in this area had to do with the soil quality itself, which was full of slab stones and clay and extremely precarious to dig through. Site 6: FloodSite number six is also by the roadside in the valley close to a stream. In 2015 there was a huge storm, however, and local people say that many of the remains were washed away downstream into the city centre. There has never been an excavation at this place, but a skull was found in a Raccoon's nest in 2002 during the filming of a documentary about the Jeju Massacre. Site 7: Farm LandThis massacre site has never been excavated. It exists at the bottom of the mountain, on farm land, where the owners have been told never to disturb the ground. There will definitely be excavations here in the future, but whether or not the land owners have kept their promise has yet to be discovered. As we were standing here talking about the land owners, and the long fight against apathy here, Mr Shim turned to me and gave his riposte to those who shrug their shoulders and proclaim they “don't care”. 'This happened to innocent people', he railed as heavy trucks charged past us on the extremely narrow road, “it could just as easily be your family, or yourself'. To Mr Shim this isn't just the apathy of the landowners either. 'This war was ratified by the UN', he told me, 'it was a global event. We have to tell the world” Site 8: Pylon As Mr Shim took me to this place two hikers passed us and asked what was going on. Mr Shim told them that we were reporting on the valley, and one of them (a man in his Seventies) told us that we shouldn't call these people "ppalgenies" (the slang word for "communist" , literally meaning "red") as they were just ordinary people. That was indicative to me of a sea change in public opinion in South Korea over the last ten years or so, and it would be rare to hear such a thing in the past.

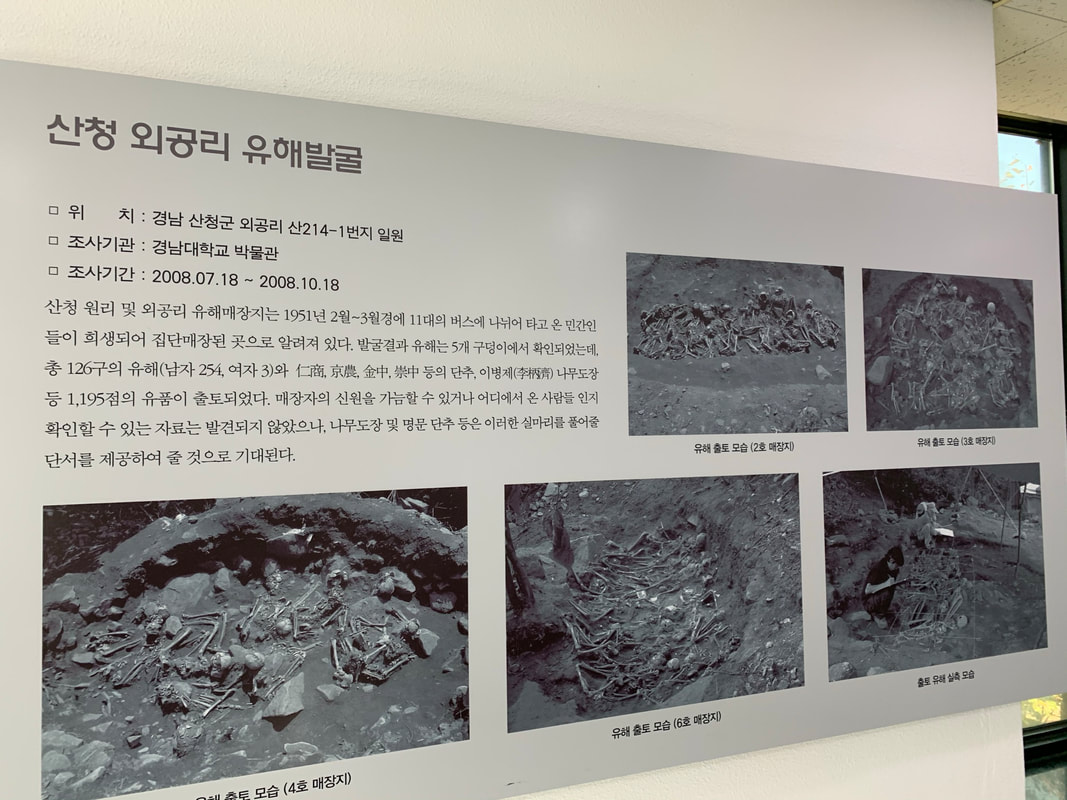

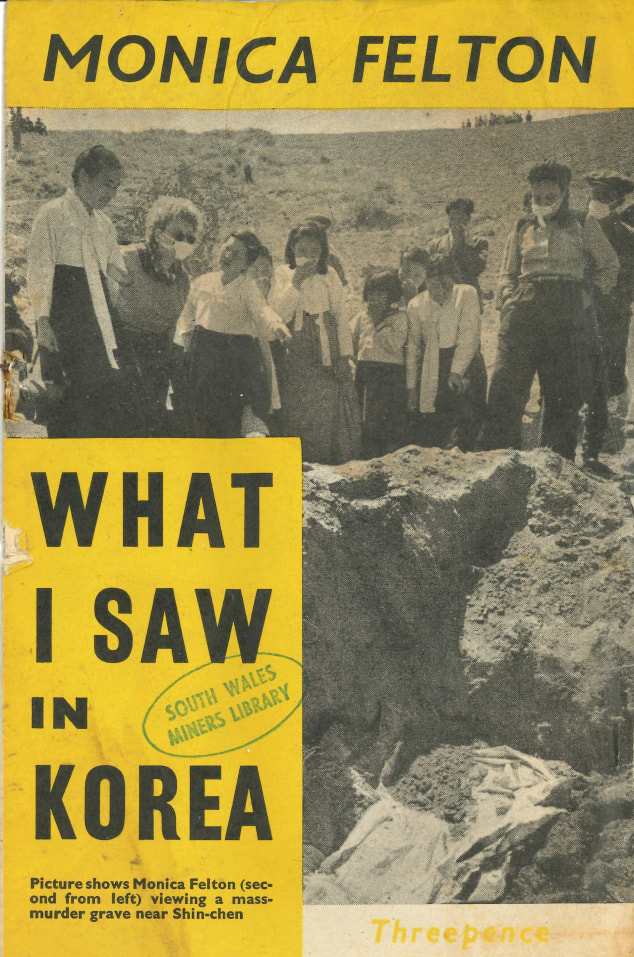

At the time the killings were witnessed by Park Song Ha from Okcheon who hid behind a tree as truckloads of prisoners were killed here when he was 15 years old. They attempted to dig here in 2007 among the trees behind an electric pylon because of another witness account, but Park Song Ha said that this was the wrong place. The bodies are buried, he tells us, underneath the actual pylon, about 10 meters to the left of where the digging commenced in 2007. When he saw them install the pylon years ago he shuddered, suddenly remembering what he had witnessed all those years ago. There is much to be written about what happened here, especially in terms of what the families suffered at this time. This place has been the subject of a poem by the local poet Jeon Sukja who's own father was killed in the valley. On the outskirts of Sejeong City this morning I accompanied Park Sunjoo to the Mausoleum where remains from the Daejeon Massacre are currently stored. This isn't just a resting place for those so cruelly murdered at this time, but also a storage facility that allows future testing of the bones. The reason for our visit today was precisely for that reason. As I arrived samples of the bones were being split into bags for a trip to Seoul where they can hopefully be identified at a later date. Once this process has been completed the families will be notified of the results, and if they want to bury the remains after all this time they will have the opportunity. When we eventually open the Peace Park in Daejeon the remains currently being excavated will also be stored on site. Hearing about all this DNA testing and how this complicated process is designed to end made me think of all of the remains that will never be identified throughout the Korean Peninsula. There will be many places like this in the North, but usually families were able to identify and bury the dead after a short period of time had passed. I would recommend people read Monica Felton's pamphlet for evidence of this. In the South, however, there was only ever an extremely small window for burials before the territory was back in control of the the American and South Korean militaries. I remember accounts of people who travelled to the site in Daejeon to recover the bodies of their loved ones at the time, only to find it impossible because of their condition. Often these people never returned to the mountain valley. It existed instead as a forbidden place at the edge of the city, a site of confluence where opposing narratives led only to a mutually agreed (or “enforced”) silence. This was a place spoken of in hushed terms by both the victors and the victims. Pain, guilt, or even ignorance, leading to a strange and terrifying omerta across the spectrum. When we were testing for DNA at the mausoleum today Professor Park showed me all of the other places that he had so far excavated for remains. One of these was the place in Gongju that originally drew my attention to this history, but there were also many others of which I had no knowledge at all. To end this post it might be worth drawing attention to one of these in particular. The ramifications of what happened at this place are instructive for many sites in South Korea, where unlike in Daejeon evidence is extremely thin on the ground. The picture above shows an excavation in a place called Oegong-ri, quite a remote area even today. The specificity of this place comes from the massacre that took place here in 1951. Nobody seems to know why these people were killed, or even where there came from. There were buttons found at the time from "Incheon Commercial School" amongst others (suggesting that many of the victims were children), but they were certainly not local people and no one seems to have come forward to claim they knew exactly who they were. All that is known is that maybe 11 buses came to this place at that time and the killing commenced soon after. Six pits were excavated in 2008.

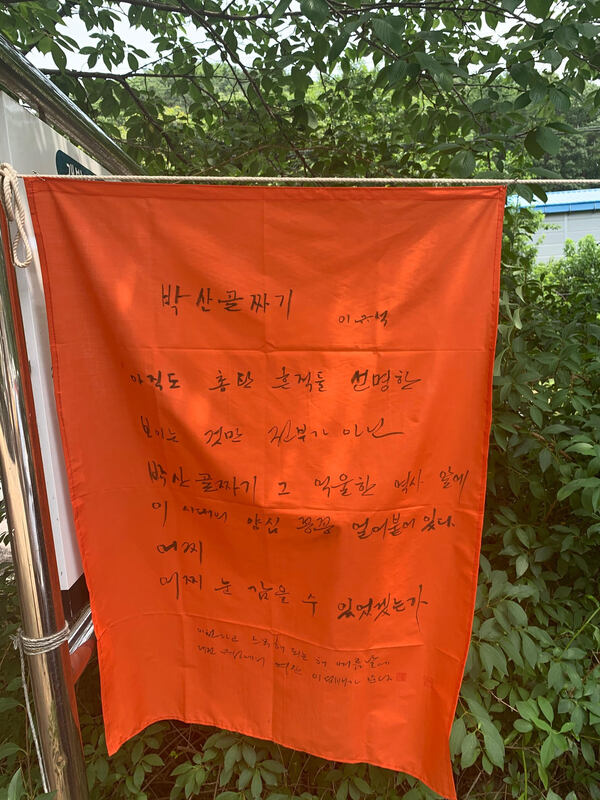

It is these kind of places that define the Korean War I think. We must focus not just on the families that received some kind of closure, but all of the people who suffered through knowing absolutely nothing about what happened to their good friends and relatives. Even the act of searching became a crime in itself, especially if the name of the person they were seeking had once been on a blacklist. The future Peace Park in Daejeon draws attention well to these unknown stories. It could bring speech and light to a place previously identified with silence and darkness. I hope in design terms that consists of a space that encourages conversation about the multiple ways in which people suffered at this time. Not just what is known as historical fact, but what could be unknown still. Which means cultivating a curiosity about the past and the future. Imagining the things that human beings have been, and could be, capable of again. One thing that has always struck me about this valley in Daejeon is the way the story always finds itself either expressed in, or involved with, poetry in both its private and public manifestations. As someone who has spent the last twenty years thinking of poetry as one way to foster an engagement -or different attention - to the world surrounding us I find this encouraging. It is something that I recognize perhaps, among so many experiences that I can only fail to come to terms with otherwise.

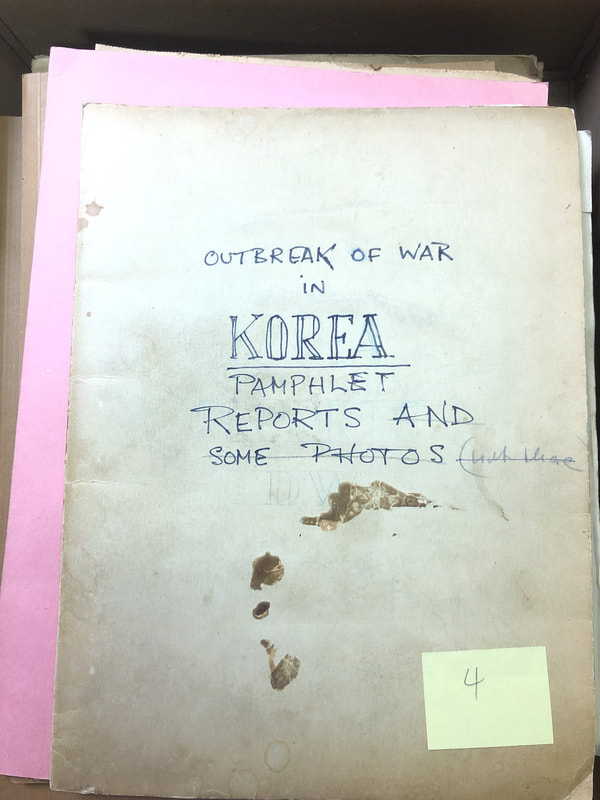

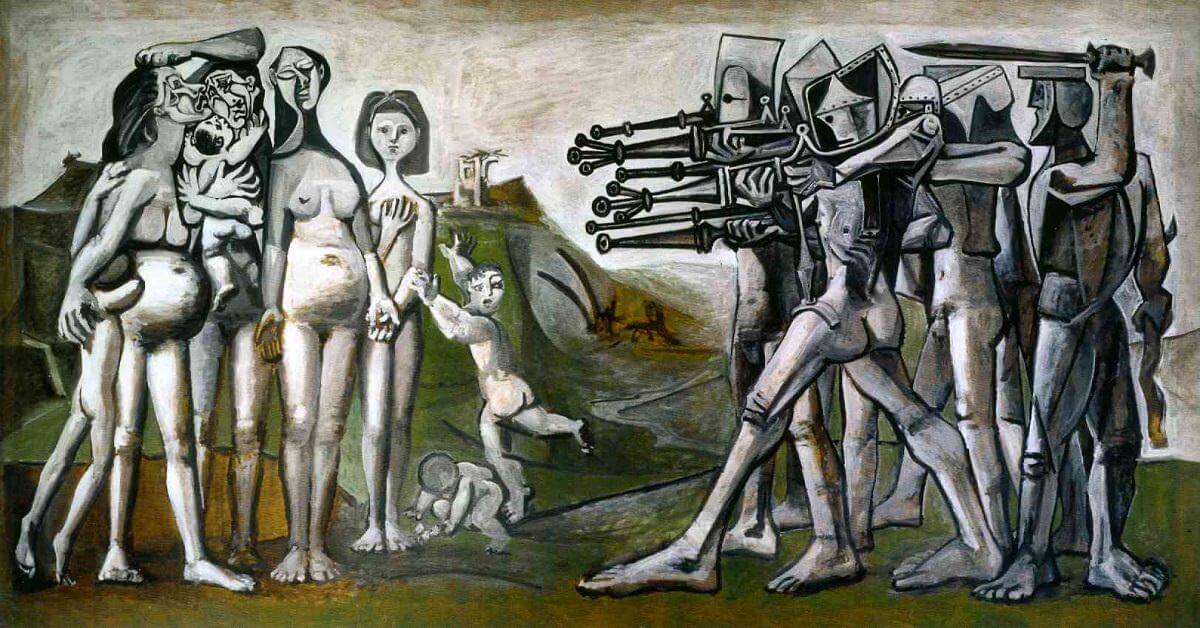

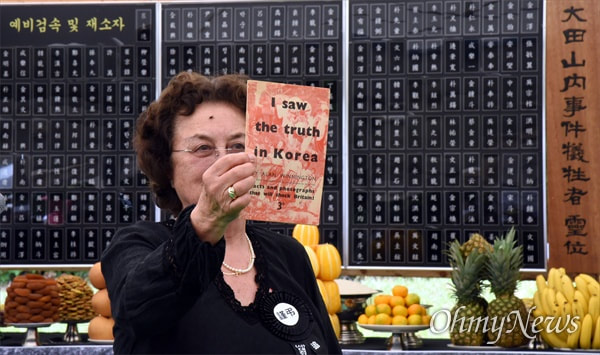

There is much to be written - and there will be shortly on this site - about the poet Jeon Sukja for whom poetry is a form of catharsis, or an extremely private and confessional way of dealing with what happened to her Father. Her story reveals one of these "untranslatable" experiences, and to see it written down and performed (always saturated with the pain of these memories) provides us with a unique and moving record of what continued to happen at this place long after fighting in the Korean War came to an end. But there are also many public expressions of poetry here initiated by the Daejeon Writers Group who I was extremely privileged to accompany to a conference on the Jeju 4.3 incident a couple of years ago. At this time of year the whole valley is usually covered in poetry banners in different colours, expressing what this history means to these writers and how it connects to other more recent historical events in South Korea. At Saturday's memorial I met the poet Park Soyoung for the second time who gave me a reading of her poem. I took my picture with her and talked about future collaborations with poets in the UK because of the Winnington connection. I hope that something meaningful can be arranged in the future.  Last years symposium on the Daejeon Massacre. Last years symposium on the Daejeon Massacre. Over the next couple of years I will be working for the local government in Daejeon in order to research the Daejeon Massacre before the building of a Peace Park here in 2024. Given the current state of the global pandemic this is proving more difficult than expected, but the goal is to have an International Conference in Daejeon at the end of this year, as well as a variety of other events that I aim to remind people of sporadically. Please get in touch if you would like to contact me about Winnington or the site in Daejeon where new information is emerging on an almost daily basis. The following posts are my first attempt to explain the work I have become involved in in South Korea. This is a project I have been part of for over three years now, but it is only at this point that I feel confident enough to speak of it as someone who knows “the facts”. As the constantly-reoccurring Tory government in the UK makes the possibility of an eventual home-coming increasingly unlikely it is about time I threw my full energy and commitment towards exploring and uncovering the reality of what happened here. Over the last few years my hometown has been Daejeon, South Korea. Whilst living here I have become heavily involved in truth-seeking work at a place where it is said 7,000 people were murdered by their own government with American supervision at the beginning of the Korean War in 1950. I will explain more about this in my next post, but for now it should be understood that this is an absolutely devastating event in Korean history that it is almost impossible to explain the gravity of to those on the outside. There are few historical parallels that can be adequately talked about in the west outside of World War Two anyway. The historian Bruce Cumings has rightly pointed to how little is known about this massacre when compared to something like Screbrinica in Bosnia. But as someone living in the vicinity it has been my goal over the past three years to find out everything I can. This is because I am adamant that it concerns not just Korea but the entire world. These tragedies result from the same mendacity by politicians, from the same warmongering and apathy, wherever they take place. That is why the more that is found out here - and we still know very little - the more I am drawn into the difficult process of discovering the truth. Let’s start with what facts there are. These are curious for me because they are at once local and global in affect. What happened here was witnessed by the English journalist Alan Winnington in his pamphlet “I Saw The Truth in Korea”. The shock waves accompanying this history extend way beyond what is immediately visible at this one place.In our recent film on this subject at Ahim Media this is clearly visible. It is a story with no closure, an attempt at truth telling shrouded in propaganda from both sides. This is because Alan’s account was dismissed as an untrustworthy source. He was exiled from the UK for fourteen years and accused of “treason”. His sincere attempt at journalism struck from the record he lived the rest of his life in East Berlin. But his pamphlet has remained for the last seventy years successfully interred in antique left wing bookshops. It’s value not in the words on the page, but a kind of ‘Communist kitsch” torn from context and unaware of the pain still existing half way across the world. But this is no longer the case. Alan has has now been front page news in South Korea thanks to the joint efforts of our organization Ahim and the journalist Im Hyoin. What is important to understand is that Alan’s report is merely the tip of the iceberg. Monica Felton - councillor for West Pancras in London and a tireless campaigner for feminism and peace during the war - was another person on the left who tried to report on massacres at Sincheon in the North. This is the place that inspired Picasso to paint an extremely powerful picture around the same time (maybe he'd been reading Alan and Monica’s reports)! But she was also investigated by the UK authorities, expelled from the Labour Party and fired from the council, with phony charges of “treason” applied to her reporting much as it was with Winnington. Her pamphlet and book “Why I Went” is similar to Alan’s. Available in the same bookshops, divorced from the reality that has always existed on the ground in Korea. For various reasons this censorship was particularly noticeable in the UK and much of it is covered in great detail within Ian McLaine's text "A Korean Conflict: The Tensions Between Britain and America" (2016). What is clear is that Winnington’s pamphlet was something that worried the state so much even mildly critical accounts of what was happening began to be censored in its wake. Apart from Monica Felton's later pamphlet, one of these instances concerns the famous UK journalist James Cameron, who wrote articles on the outbreak of war in Korea for the Picture Post. In a special edition Cameron and a photographer called Bert Hardy attempted to publish an article called “An Appeal to the UN” with images and text carefully arranged to favour neither side in the conflict. There were pictures of prisoners in Busan being treated terribly, but there were also pictures like this one of American troops in the North made to parade around dressed like Hitler with Stars and Stripes trailing behind them. In his autobiography Cameron talks about the care with which he had written and edited this article before it was published, as well as the ways in which he tried to strip it of all emotion and just present the ‘facts’: “Finally we agreed on a layout which in the circumstances was the most tactful and unsensational possible. We used only those pictures of the prisoners which would establish their dire condition without unnecessary shock; my article was written and re-written over and over again until it became almost bleak in its austerity” The Times and The Telegraph newspaper in England had already written similar articles on the Korean War at this time. Even the conservative papers in the UK were critical of the brutality with which prisoners were being treated. ‘My article amounted to a vigorous plea that if our ally Dr Synghman Rhee saw fit to use methods of totalitarian oppression and cruelty’, Cameron explains in his autobiography, ‘it should not be done under a UN flag”. This issue of the Picture Post was never printed. The press was turned off before it could reach the public. It’s editor – Tom Hopkinson – had to leave the magazine after its Conservative owner Sir Edward Hulton feared he would be breaking the law. These pictures and opinion pieces were never actually published at all. Even though they are often used in discussions of the Korean War they are torn from any context and people seem largely unaware of their origin. The only reason they even exist today is once again because of the Daily Worker who leaked some of the pictures and published them under the headline “KOREA EXPOSURE SUPPRESSED – PICTURE POST EDITOR SACKED”. The Picture Post was eventually taken out of circulation in England completely. It became a shadow of its former self, desperate to avoid any hint if opprobrium from the state. These images on the road to Gongju were also included in the suppressed version: The picture above was one of a series quickly snapped by an Australian photographer as he passed by the scene at the beginning of the war. It's power rests in how it captures a moment that otherwise would be lost in time. Photographs like these speak a truth that needs no accompanying words and it is easy to see why the decision was made never to print them. In 2008 The Truth and Reconciliation Commission of South Korea used the photo above and witness accounts to find the exact place in which these people were so cruelly slaughtered. In South Korea there are likely many places like this that have since disappeared under apartment blocks, or simply have no living witnesses able to reconstruct the story of what went on. This doesn't even take into account the terror with which any surviving family members were subjected to under successive dictatorships. For a bold and compassionate look at this see Hwang Sukyoung's text "Korea's Grevious War" (2016). It is important to know that these events did not exist in isolation and were deliberately suppressed. They were part of a series of state sanctioned killings - often referred to as the Bodo League Massacres - that took place all over Korea at the beginning of the war. These massacres peaked thanks to the brutality of the first South Korean President Synghman Rhee, but continued in a wave of revenge killings and cycles of violence until the end of the war. The Korean War may have ended in a stalemate, but the civilian toll suggests the complete opposite of a draw. From the killing of suspected communist prisoners at the beginning of the war, to the awful treatment of North Koreans after the Incheon Landings, the eventual death toll of civilians is 2,730,000 even when relying on the most conservative estimates. This includes deliberate strafing of refugee columns by aircraft, the endless bombing of cities, as well as the senseless massacres already covered above. That is why I was so glad to find an archive of Alan Winnington’s notes and journals at Sheffield University earlier this year with the help of his eldest son Joe. Thanks to the mayor of Daejeon - Hwang In Ho’s - letter, we were able to visit and find some incredible primary sources about what happened at this time. The archive is still uncatalogued, so it was incredibly generous of the person in charge (Chris Loftus) to allow us access. The Winnington archive - from my own experience - will be able to provide much needed information that either refutes or backs up both first hand accounts and official versions of the narrative around these civilian deaths. Further to this on the seventieth anniversary of the Korean War critically evaluating these sources has the potential to genuinely contribute to research that will inform the curation of information and exhibitions in a peace park that will be built on the site that Winnington visited in 2023. This is why the search for truth is so necessary, even when on the ground in Daejeon it seems long overdue. The word repeated by those in charge of the museum project is an English one: "healing". All information can only add to this important goal. I will be visiting Sheffield regularly in the future and hope even more of interest can be discovered. Read these three articles by the journalist Im Hyoin (In Korean) if you want to get a sense of our trip, including an excursion to Cable Street and Marx’s Grave at Highgate (both places associated with the beginning and end of the political journey of Winnington himself): http://www.joongdo.co.kr/main/view.php?key=20191118010007506&fbclid=IwAR3ApkfAXayJWEXOwRbu7LWLXObHWzSHrltprWBjkKSbpY-aSapRVmJTWro http://www.joongdo.co.kr/main/view.php?key=20191119010008052&fbclid=IwAR16wtt_K-uY2uwrtEoNv4Qh5g42LKD97KGjGluYLKfs7o9bp0fHdvZjQWo http://www.joongdo.co.kr/main/view.php?key=20191124010010053&fbclid=IwAR09z6ZwdWFEM_nT2FuDiNsg1mGaDaatGZkyYKQuA3pihqTCZhRcGs6qIAQ In 2019 our production company Ahim Media (with the help of the donations from Daejeon citizens) invited the widow of Alan Winnington (Esther Samson) to South Korea. In all of the posts that follow I think nothing speaks with more wisdom, conviction and clarity than the words of Esther herself who gave a short speech at the memorial where she held aloft Alan’s pamphlet (the subject of my next post) in a gesture of defiance that moved me greatly. It is to the Bereaved Families Association of Daejeon, Esther, her son Joe, and Alan's grandsons Thomas and Jonathon to whom I dedicate these series of posts on Korea. As time passes I am confident we will find out much more together. A MEMORY OF ALAN WINNINGTON

I first met Alan in Beijing in 1949 when he was a foreign correspondent covering the civil war in China for his English Newspaper. I was his interpreter and assistant. When the Korean war broke out in June 1950 he was sent by his paper to cover a war that he thought would be over in weeks. He stayed until in the end of the war in 1953 and on one of his rare visits back to recuperate from the dreadful conditions in Korea, we married. He witnessed unspeakable horrors - indiscriminate bombing of innocent civilians, and the use of napalm dropped on the population. Alan described a five year old boy, his face and body horribly burnt, with no eyelids and his weeping mother saying “who will marry him”? not realizing her son would not survive. It affected Alan for the rest of his life and he could never get over the pain and misery he saw because of the war. But the most horrifying description was when he visited the mass grave in Rangwul near Daejeon of thousands of intellectuals slaughtered by the authorities with bodies barely covered with soil. He wrote a pamphlet likening it to the Nazi slaughter in the concentration camps. His report of what he witnessed was suppressed by the warring parties and Alan was branded a traitor by the British Government, his passport confiscated and if he returned to Britain he would of faced charges of treason. Not a single British or American journalist paid a visit to Rangwul to investigate and Alan was exiled from his country for twenty years for exposing the truth. He died in 1983 too late to realize his sacrifices for exposing the crimes against humanity had not been in vain and acknowledged by those thousands of intellectuals massacred by the warmongers. Esther 27/06/2019 |

Categories

All

Archives

April 2023

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed