|

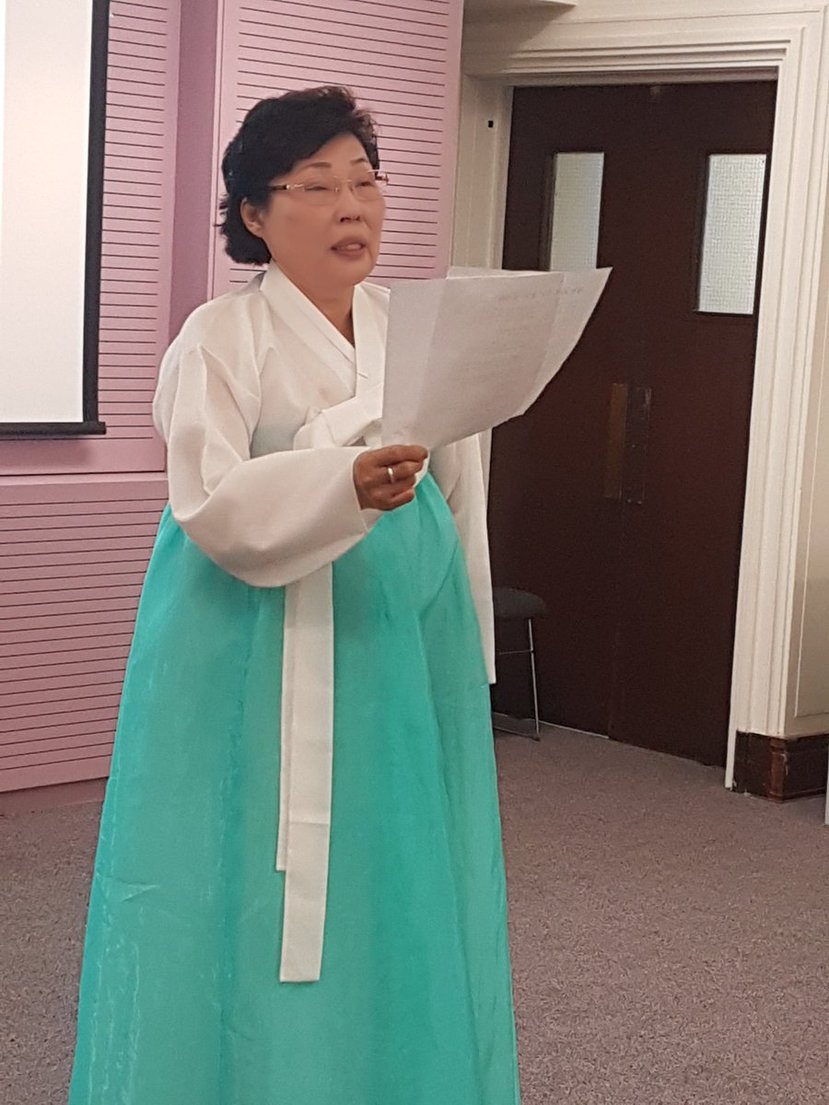

In the first half of 2018 I was privileged to be involved in The Longest Tomb, the first documentary on a politicide in Daejeon aided and abetted by the US military in 1950. We took the film to SOAS with Mr Lee and Ms Jeon at the end of May this year. Ms Jeon read two poems, which I then explained to the audience. There was also a lively discussion at the end of the event. I truly hope I can find a copy of Ms Jeon's reading to put on this site. I will add a link to this post if one emerges. In the meantime please watch the above film, another version of which we hope to premiere in the US (Washington DC) in 2019.  Ms Jeon reads from her poem "A Wood Pigeon On The Pylon" Ms Jeon reads from her poem "A Wood Pigeon On The Pylon" There is one review of the event on Tongil news in Korea (In Korean, obviously). Click the following link: http://www.tongilnews.com/news/articleView.html?idxno=125044 There is also a similar review of the Korean premiere here: http://www.joongdo.co.kr/main/view.php?key=20180519010007868  ‘Since therefore I also am how do I entreat thee to come into me, who could not be, unless thou were first in me” - St Augustine Confessions Book 1 In recent years two words have been foregrounded in Scott Thurston’s work: ‘knowledge’ and ‘reassembly’. ‘Reassembly’ was an intrinsic part of Reverses Heart’s Reassembly (2011), whereas ‘knowledge’ has always been pitched as something reliant on ‘an encounter’ with the other person (29)[1]. This isn’t ‘Knowledge as power’ (like in the ubiquitous proverb) then. As Steve Boyland notes in the blurb for Figure Detached, Figure Impermanent (2014) this volume works loosely in the kind of quest that engaged St Augustine and Dante. If I was to generate my own blurb for this pamphlet perhaps ‘a quest for knowledge with a difference’ would be appropriate. Whereas in St Augustine and Dante the ego was inextricably linked to this quest, in Thurstons pamphlet it is viewed with suspicion. ‘In the gap between me and I’, wrote Thurston in Reverses Hearts Reassembly, ‘you draw nearer’. The trope drawn upon in Thurston’s last major text was dance (initially Gabriel Roth’s Five Rhythms), seen as a metonymic process for how a transaction like this operates. Writing of this aspect of his work Frances Presley has explained how poetry and dance coalesce. This doesn’t mean drawing parallels between each activity, or aiming for sweeping generalizations of ‘sameness’, but measuring some facets of each that make creative aesthetic practice possible. ‘Both dance and poetry are not so much about learning a discipline’, wrote Presley in 2011, ‘but about finding the discipline of form which corresponds to your desires and needs’. Poetry and dance are not classical forms to be blindly repeated and perfected, but meaning-making strategies that stand out in their capacity to privilege protean states of interaction with the world. These strategies are, firstly, improvisatory, but also socially-orientated in their recognition that both writing and dance allow those engaged in these activities to approach a new framework of thinking. ‘The tension between intention to move and moving’, as Thurston writes in Reverses Heart’s Reassembly, ‘between dancing by yourself and with others’ (33). This is an interaction I will explore in some detail using Thurston’s text Figure Detached, Figure Impermanent (2014) describing what I think are his own ‘desires and needs’. This is a language-based excursion that will leave ‘theory’ by the wayside. The writing will speak, as it were, for and beyond itself. Rather than being a text ensconced in some theory or other, this is a pamphlet that pays dividends for those who read it. Figure Detached, Figure Impermanent calls for our engagement with the other person, something that is surely part of the ‘message’. This means it does not lend itself to impositions, but a dialogic approach instead. This is because it starts from where the other texts left off. This is not a text to be picked up and read from cover to cover, but one to fall into at any point on a journey of self-discovery (where ‘self’ has been dutifully elided from the equation). Interestingly, the unnumbered pages of text point us in that direction. Nothing will be gained from what lies within if we expect the consistency of tone and voice associated with more traditional narratives. ‘Draw your efforts towards the spectacle of the line’ writes Thurston early on, ‘noting the lessons of the fowl on the land, on the water, and in the air’. Making the most of work like this involves a variety of strategies involving careful listening and attention. Edification comes not in a revelatory ‘knowledge stream’, but a consistent engagement with a language buzzing with signs of life. ‘The fowl’, after all, ‘uses different parts of its body on its own journey through space and time. The reader must be prepared to encounter the text in a similar way. Whatever we ‘know’ becomes immediately insignificant next to what another person can teach us. ‘Redemption in resistance’, writes Thurston, ‘to knowing what’? The problem always comes back to our vainglorious refusal to pay attention. All forms of knowledge, in this sense, are seen as exclusionary narratives that of necessity elide different modes of attention that should be in dialogue with each other. Rather than looking for a ‘correct path’ through the text the goal is to recognize knowledge itself as something permanently in flux. An ever-shifting nucleus of ideas, that even when they encounter resistance, must remain in constant dialogue with exteriority. Knowledge is not generated in Thurston’s text by the heroism of an individual choosing the ‘right path’ but by a more fluid attention to complexity. ‘Is a flung headlong youth’s assertion of thundering drums what breaks the bowl’, is the question posed at the very beginning of the poem, which is immediately followed by the phrase ‘let it go’ as well as more references to being ‘reassembled’. This is a ‘quest’ that must be repeated ‘over and over’. We are not involved in reading so that we can ascend to position of dominance, but as part of a continual process of knowledge acquisition instead. In that sense I am in interested in two words that appear in the initial stages of the poem. The first of these is ‘flow’. This draws my attention because it suggests the flux and change implicit in images of water, but also a sense of ‘creative flow’ or that psychological state in which creative work is said to happen. As the second isolated portion of text states: A series of trials set up like an island in a river – noticing where a current is viable even in concealment. A perfect will turns like a needle as a thread of disgust stitched through every day starts to come undone. You slip into the stream. Trials in Figure Detached are once again described using images of fluidity as ‘islands in a river’. The perceiving subject sees them as somehow separate from the water itself, even though in reality they are part of the ebb and flow. If these islands are to ‘stand for’ anything (although I’m not sure if this is Thurston’s intention) it could be a linear series of possibilities predetermined from the start. When the water shifts unpredictably around them, we follow ‘viable currents’ even though they are not visible to the naked eye. But this ‘perfect will’ we cling to is actually a ‘thread of disgust’ that can easily be ‘reassembled’ into something else. Which brings us to the final isolated line of the text: ‘you slip into the stream’. Rather than a sense of preordained ‘islands in the river’ the sense is of an accidental ‘slip’ into a ‘stream’ that overwhelms us. But as always this language creates a conflictual sense of multiple meanings. This ‘slip’ could be ‘slipping’ on a pair of socks, or ‘slippers’, something more comforting. Just like ‘slipping’ into a warm bath, this adds to the conflictual nature of the message. Either way instead of a predefined route we have an openness to experience, spontaneity or accident. But there is also another allusion here. Thurston has effectively taken apart (or ‘reassembled’) the word ‘slipstream’ to give it another meaning entirely. This slipstream, remember, is what moves us forward in time. It is propulsion, or ‘flow’, that provides the velocity for that aforementioned ‘fowl’. For the writer it is ‘creativity’ – ‘the midnight oil’ – all of the romantic clichés that saturate (and burden) accounts of how scribbling egos operate. This sense of certainty is completely disrupted to give an alternate - almost clownish – sense of stupefaction in the face of what presents itself as ‘truth’. Suddenly we flounder, fishlike, where once there was precision. It isn’t as if what we know is being mocked nihilistically in lines like these, but rather that its status is being called into question by the function of language itself. This is one of the most compelling features of Figure Detached, Figure Impermanent (2014). ‘Consenting out of fear you grasp each word as a thing’, writes Thurston, ‘trying to create your own knowledge’. The impetus is always on the other person to ‘prove.. you reflect the thoughts I think’, as Thurston puts it. This brings us to a second oft-repeated image in the text, that of ‘bowl’. From the beginning of the text the ‘bowl’ is what is broken by the ‘youth’s assertion of thundering drums’. ‘The Bowl’ at this point seems a rather random occurrence in the poem. A clue, however, comes on page ‘eight’ (unmarked) when Thurston writes: The greater the measure of virtue, the more the fungus attaches to the base of the bowl in the mind. Two fish weigh the task of care – clear and unctuous – beneath the wintering flowering plum, beneath the crazed glaze. The heart overflows the gilded rim. ‘Bowl’ is clearly associated here with the bowl of the mind, or the cup of the skull, the locus at which most ‘thinking’ happens. Moreover, it is the base of the brain that makes speech possible as the neurological stimulus for communication itself. Without it individual thought processes would be echo chambers, reflecting nothing but a monologic certainty. But ‘virtuous’ thinking is associated in Thurston’s conceptualization with the ever greater accumulation of fungus. The bowl of the mind can be a place of stagnation as much as it claims to be a righteous discourse. In a startling juxtaposition the reader immediately encounters more water-based imagery this time of two fish ‘weighing the task of care’. These fish are interesting precisely because there are two of them. ‘Clear and unctuous’ they are wonderfully juxtaposed to the fungus inflamed ‘bowl in the mind’. Their major function – in juxtaposition – is one of ‘care’. Their ‘unctuousness’ in itself opens up a whole series of possibilities. Firstly, there is the a linguistic association with ‘sheen’ or ‘oily shine’ that sets them apart from the fungus growing in the mind. But, secondly, there are connotations of ‘servility’, in as far as that word has come to stand for a sycophancy the polar opposite of the ‘virtuous’ knowledge in the fungi infested ‘bowl’. But the presence of the fish again gives a conflicting sense of a ‘goldfish bowl’, an idiom associated with being trapped or introverted. In Figure Detached this seems to be where the major aesthetic efforts lie. Language is presented as a vastly conflictual entity constantly ‘reassembling’ itself in contact with the other person. This brings us back to that curious phrase ‘redemption in resistance’. Redemption only comes in the resistance, or conflict, between ‘virtuous’ knowledge and its contact with the other person. This is enacted in the text by an attention to the connotative realm of signification, which is clearly meant to surprise in its constant twists and turns. As Thurston makes clear below: A man stands by his neighbour; opens him up to see how he works; viscera sliding out like abandoned fears. Discovering the thigh muscles he becomes fascinated – eternity’s too short. Still thinking about time, he finds it more difficult to create than destroy, as he starts to extend into the space beyond his skin. When taking apart an interlocutor Thurston finds not some gleaming mechanics, but a disappointing organic mess. This is the true essence of the human, the not so surprising fact that there is nothing that makes us unique. The ‘viscera sliding out’, interestingly, doesn’t communicate a sense of horror, but something more like ‘relief’. The abandoned fears might be that the mortality of this person is nothing to envy, or there is a seeming equality that was previously absent. The onus now must be to ‘create’ rather than ‘destroy’. The knowledge of a shared mortality should be something liberating above and beyond our most selfish instincts for domination. The key to this passage is notable the ‘thigh muscle’, which is described as ‘fascinating’. This is because the thigh muscle provides a way out of the ‘create’ or ‘destroy’ paradox. Escaping our most base intentions the thigh muscle is the part of the body that enables movement, and therefore makes another kind of consciousness possible. Next to the hip, attached to the femur by connective tissues, there would be no walking without the kinetic energy generated by it. This is the only route to what Thurston called in Reverse’s Hearts Reassembly ‘the transition world entangled in the interhuman’ (13). As readers we enact this process ourselves. Twirling back and forth through Thurston’s text, looking for linguistic clues, we become part of the dance in our explorations and engagements. This is a difficult, but liberating process. But it is one nevertheless fundamental to all attempts at ‘knowing’ and mimics the action of reading itself. [1] I am referring here to the ‘knowledge’ section of Reverses Hearts Reassembly from p. 25 onwards. |

Categories

All

Archives

April 2023

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed