|

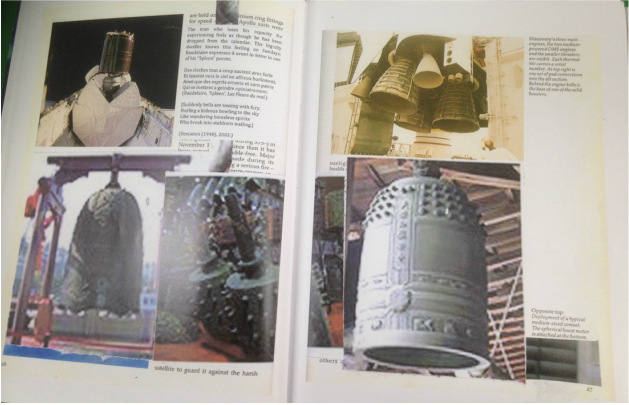

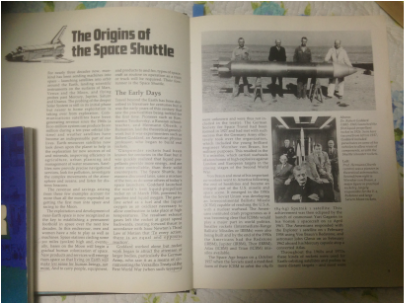

Read SPUTTOR 5 here In my post on ‘human anticipation’ I noted that history in SPUTTOR is associated early on with blue and a sense of the ‘intangible’. This is against the irretrievable history in Richter earlier. There is hope to be squeezed out of contemporary conditions, but this hope is not something that is easily located. In “Complexity Manifold 2” Fisher writes of ‘the aesthetic swerve’ as fundamental in this context. This is a phrase taken from Joan Retallack’s The Poethical Wager (2003) who in turn borrowed it from Epicurus[1]. For Retallack aesthetic swerves are necessary devices to jolt readers out of complacency. During “Complexity Manifold 2” Fisher quotes Retallack defining a ‘poethics’ as ‘what we make of events as we use language in the present’, or ‘how we continuously create an ethos of the way in which events are understood’. ‘Swerves’ are necessary because they ‘dislodge us from reactionary allegiances and nostalgias’. History is only ‘retrievable’ if formal concessions are made towards recognizing this situation. Otherwise poetry remains just another form of ‘self deceit’, something resistant to interpreting the conditions that surround it. Indeed, there seems little point in writing if the goal is to simply reassert a reality that has a chokehold on the truth. But the medium of poetry seems especially resistant to attempts at ‘innovation’ in the popular mind. It must be a region of comforting traits where language conforms to preconceived notions of what poetry is. Retallack contrasts this view with commonly accepted perspectives on the role of science in public life. ‘There are numerous versions of these qualms about the efficacy of experimental thought’, she writes, ‘except in the sciences, where it is seen as the nature of the enterprise’ (5). These arguments are well-rehearsed. ‘Give up the poem’, as William Carlos Williams famously put it in Paterson, ‘give up the shilly-shally of art’. The parallels to Fisher’s own work are immediately striking. ‘He had become the subject of the manifestation of truth’, writes Fisher of his own predicament, ‘when and only when he disappeared or he destroyed himself as a real body or a real existence’. But this isn’t the immediately recognizable ‘death of the author’. Instead of ‘disappearing’ completely any tyrannical hand is rendered diffuse over a greater area. As Retallack insists, ‘agency’ must be seen in ‘the context of sustained projects’, where ‘swerves occur, but which one guides with as much awareness as possible’ (3). These ‘alternative kinds of sense’ result in an entirely different order of perception. ‘Control isn’t bad’, as Fisher once explained in reference to the scientist Arthur Eddington, ‘if it’s your own control over your own self’ (51). With this knowledge the blue in SPUTTOR stands for the unknowable qualities of meaning beyond human perception. The mark of the author, in opposition, will always be red. Any trace of personality is embargoed from the start. The author is not erased, but ‘damaged’ from the outset. On pages 26 to 27 the guide is Walter Benjamin, who famously examined the possibility of interrupting monolithic historical narratives through what he termed aesthetic ‘shocks’. ‘The present’, as Benjamin had it, ‘is an enormous abridgement’. ‘The history of civilized mankind’, as he paraphrased the words of a “modern biologist” during his “Theses on the Philosophy of History”, ‘would fill one fifth of the last second of the last hour’ (255). As already made clear, such a ‘revisioning’ is a major focus of SPUTTOR itself. As Fisher writes of the current epoch, we are at the very end point at which a plan for the resuscitation of human history will ever emerge: This period of stability, the Holocene (entirely recent stability) is almost certainly now under threat. A new era has arisen, the Anthropocene (human recent, coined by Paul Crutzen) in which human actions have become the main driver of global environmental change since the industrial revolution in Europe. Johan Rockström and 28 colleagues (including Crutzen) from the Stockholm resilience centre, propose a framework based on “planatery boundaries”. These boundaries define the safe operating space for humanity with respect to the earth system, and are associated with the planet’s biophysical subsystems or processes. By drawing our attention to such a time line Fisher aims to displace the anthropocentricity of ‘universal history’. Leaving the planet in SPUTTOR is an attempt to gain a new perspective on this distinctly human dilemma. The shrill, and conceited, trajectory of human ‘progress’ has to realise its limitations if the human race is to survive. The melioristic conception of time that makes manufactured ecological ‘boundaries’ necessary is responsible for the ‘self deceit’ that currently burdens human thinking. In the light of these extreme conditions, and in the same manner that Benjamin had attempted, it is impossible to conceive of history in the first place without acknowledging the duplicitous state narratives informing it. ‘The concept of the historical progress of mankind cannot be sundered from the concept of its progression through a homogeneous, empty time’, as Benjamin put it long ago, ‘[a] critique of the concept of such progression must be the basis of any criticism of the concept of progress itself’ (252). At this stage in SPUTTOR the main textual element switches from poetry to the juxtaposition of fragments much like in Benjamin’s own work. On page 26 Fisher includes quotations from Benjamin during “On Some Motifs in Baudelaire”. Here, the writer comments on one of Baudelaire’s Spleen poems which describes ‘bells’ ‘tossing with fury’ amongst ‘homeless spirits’ ‘break[ing] into stubborn wailing’. What Benjamin was interested in identifying in Baudelaire was the alienation of a human race that has ‘los[t] its capacity for experiencing’. This is experience of time in the city as it has been wrenched from reality. ‘Although chronological reckoning subordinates duration to regularity’, wrote Benjamin in the original sentences preceding Fisher’s isolated text, ‘it cannot prevent heterogeneous, conspicuous fragments from remaining within it’ (336). No matter how hard the dominant historical narrative imposes itself on the idea of human progress, glimpses of alternatives emerge. The bells in Baudelaire’s poem – ‘tossing’ with ‘fury’ – are juxtaposed in Fisher’s ‘damaged’ text with the ‘engine bells’ on Challenger. On pages 26 and 27 it is possible to see two aspects of the space shuttle design mirroring a bell shape common in fractal geometry. The bells in Baudelaire’s poem clearly hold some as yet unknown affinity with the ‘engine bells’ on Wilson’s photo of the shuttle. This is a relationship that sees the trajectory of bell design as something interpreted over and over again outside of human history with different modifications each time. Rather than viewing time as progressing in a teleological fashion towards an inevitable ‘human improvement’, rocketry is seen in terms of an expanding series of which it is an inevitable part. The idea of the shuttle is simply a modified version of a shape that occurs somewhere in nature. Human appropriation of this design refers to no innate genius in the species. According to Fisher’s ‘Image Resources’ section the bells in SPUTTOR include the JINGYUN bell, and the Xi’an bells from ‘the warring states in the Hubei provincial museum’, but also the ‘Ryoan Ji’ bell contained in the ‘Temple of the Dragon of Peace’ in Kyoto (127). Unlike in Wilson’s text, these fractal shapes have been put to numerous uses throughout human history rather than being appropriated within the terms of shuttle design. Bells such as these escape tribal boundaries or affiliations synonymous with state power. Used in war, and times of peace, such bells also exist in cultures with cyclical understandings of time the very antithesis of the linear model informing the Challenger mission. On pages 26 and 27 of SPUTTOR Wilson’s original text takes on another transformation. Rocketry is glimpsed from within the prism of an ever-expanding complexity. Technology is separated from its violent origins in the west and revealed as part and parcel of a much wider condition. Kyoto – the location of the ‘peace bell’ – opens up a further series of connotations when considered within the context of the nuclear bombs that where dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki in the closing stages of the Second World War[2]. As the ultimate manifestation of the indefatigable belief in rocketry, the erasure of entire cities points to an imbalance in how technology is perceived at this ‘human colloquium’. Instead of ‘a bumper year for space achievements’, its cynical use has become simply another way of ‘perpetuat[ing] the state machine’. On pages 28 -29 of SPUTTOR this reading of history is confirmed via another section from Benjamin’s essay. The first day in November, the Day of the Dead, is seen as absent from western narratives of progress like that enshrined in the Challenger mission. ‘The duree from which death has been eliminated has the affinity of a bad ornament’, writes Benjamin of Baudelaire’s poem, ‘[t]radition is excluded from it’ (29). ‘The melancholy man sees the earth revert to a state of nature’, the theorist continues, ‘[n]o breath of prehistory surrounds it – no aura’ (29). But Fisher juxtaposes across from Benjamin’s new quotation a section from Adorno that criticizes the theorist’s method. There is an element of self-reflexivity here aiming to comment on the formal progression of Fisher’s own text. The chosen quotation is taken from a well known exchange between Adorno and Benjamin that has come to define all future work aiming to proceed by the juxtaposition of text and image. In the quotation from SPUTTOR Adorno criticizes some lines from the Arcades Project when Benjamin refers to the dialectical image as ‘utopia’ or ‘dream’[3]. As George L. Dillon has made clear in his essay “Montage/ Critique: Another Way of Writing Social History” (2004), which draws heavily on John Berger and others who have attempted to use Benjamin’s procedure in their own work: [Benjamin’s example] points to certain practical issues about writing by juxtaposition and constellation of fragments (montage). The fragment, or more broadly the constellation, must speak for itself: this means not only that a single definitive authorial perspective must be removed, but also that the fragment/ constellation must remain open to further seeing. Adorno feared that by this evacuation of subjectivity (of the interpreter), Benjamin had inadvertently presented a view of the world as mere uninterpreted fact – of material, observable things, and unique, unanalyzable events – which the reader would have no reason to connect to theory at all.” (3) Benjamin’s dialectical image, in this sense, could represent a stopping of the processes that are so important to Fisher. Adorno’s critique continues to have major ramifications when considering text and image in alignment in this manner. The author cannot simply ‘vanish’ from the text, and leave interpretation open to a small circle of ‘true believers’ who are able to ‘get’ the references put forward. ‘Benjamin could not resolve the contrary objectives of author-evacuated montage presentation’, writes Dillon, ‘and the need to provide theoretical, ethical guidance for the reader’ (3). If Fisher is ‘guiding… with as much awareness as possible’, to use Retallack’s words earlier, ‘then it seems obvious that SPUTTOR is attempting something contrary to the usual ‘author evacuated montage’. Perhaps this is why page 28 shows Fisher’s automatic writing with that ‘screwed up’ piece of paper resting on top of it. To avoid Benjamin’s own predicament, the ‘damage’ in SPUTTOR is an element that attempts to rectify these fundamental difficulties in composition. SPUTTOR is not dialectics ‘at a standstill’, as Benjamin put it, but a genuine attempt to interfere with any idea of ‘utopia’ or ‘dream’ that might come from the constellation itself. The authorial red in the text has been focussed from the outset upon disrupting precisely such claims. Fisher’s text, then, is not ‘parrhesia’ in the sense of rhetoric. On page 31, for example, it is clear that this ‘truth telling’ is itself subject to a kind of ‘double damage’. ‘PEAR EASIER’, as Fisher mockingly reorders this vital word, will not escape scrutiny. ‘Truth telling’ will emerge independently in SPUTTOR, there can never be the kind of ‘uninterpreted fact’ of which Adorno accused Benjamin. The ‘parrhesiast’, as Foucault explained in The Courage of Truth, ‘is not a professional’ (14). By the same token it would be wrong to situate SPUTTOR as an attempt at rhetoric plain and simple. To use Foucault’s description of the term, parrhesia is more like a ‘stance’ or ‘mode of action’. The parrhesia in SPUTTOR comes not from what kinds of things are said, as much as the way they become articulated in the first place. On the bottom left of page 29, for example, Fisher reappropriates the words of the Invisible Committee, to give a sense of precisely why such strategies are necessary. In Fisher’s ‘found poem’ different sections of the Committee’s text are presented in a collage that defines our contemporary SPUTTORings. ‘Certain words’, a section of Fisher’s Invisible Committee collage reads, are like battlegrounds, their meaning, revolutionary or reactionary, is a victory to be torn from the jaws of struggle’ (28). The word the Committee is referring to at this point – “communism” – is precisely the kind of concept it is almost impossible to utter in the present. At the time of writing, when a Conservative government has once again taken the reins of power in Britain, a word such as this will be further suffocated beneath a self congratulatory discourse that sees it as something abandoned within the liner progression of time. But writing like SPUTTOR is necessary because without the method of the parrahesiast there can be no attempt to picture language outside of the universal history within which it has become embedded. In Fisher’s found poem The Committee writes of a ‘drone’ that was discovered in the suburbs of Paris ‘unarmed’, which ‘gives a clear indication of the road we’re headed down’ (28). Rocketry isn’t simply a benign historical ‘spectacle’ at the culmination of human progress, in this sense, but something that has spread out to encompass all aspects of everyday life. The drones may not be armed in this time of relative ‘peace’, but you can be certain that they will be once the interests of the state are threatened. The beauty of Fisher’s poem comes in how urgently it speaks from within the gaps of the sanctioned, and sanctimonious, discourse of the present, without abandoning himself to the ‘stand still’ of the ‘dream’ that haunted Benjamin. To do otherwise would be to replace one form of ‘self deceit’ with another, an authorial imposition that does nothing to heal the fissures that blight the anthropocene itself. [1] 'Epicurus posited the swerve (aka clinamen) to explain how change could occur in what early atomists had argued was a deterministic universe that he himself saw as composed of elemental bodies moving in unalterable paths', writes Retallack, 'Epicurus attributed the redistribution of matter that creates noticeable differences to the sudden zig zag of rogue actions. Swerves made everything happen yet could not be predicted or explained' (2) [2] The location of the ‘peace bell’ in Kyoto is interesting to consider. The original target for the first A-bomb, Kyoto was taken off the list of targets after the obliteration of Dresden had caused such controversy. The bombing of Nagasaki and Hiroshima, then, could be seen as an early attempt at twisting the narrative of rocket technology within the terms of state propaganda. This is without even considering the mind boggling rumours that the US Secretary of War Henry S Stimson was reticent about targeting Kyoto as he had been a regular traveler to this area of Japan before the war even enjoying his honeymoon there [3] ‘Ambiguity is the figurative appearance of the dialectic, the law of the dialectical at a stand still’, to quote Benjamin exactly, ‘this standstill is utopia, and the dialectical image is therefore a dream image’ (Arcades 171).  The first pages of 'human colloquium' (22-23) The first pages of 'human colloquium' (22-23) Read SPUTTOR 4 here One way to approach Fisher’s texts is through the open field that informs them. In the case of SPUTTOR this process has become far easier than it would have been for an earlier text like Place. To get a sense of SPUTTOR I downloaded what I could from the website bookzz.org, which I have found to be an excellent short cut for obtaining resources in the past. But it is also possible to approach SPUTTOR without these materials. Reference to a dictionary, for example, identifies colloquium as both ‘seminar’ and ‘hymn’. This section is identifying what is at stake in the poem, whilst conceptually justifying what will follow. SPUTTOR is human reflection. The text is a well-calibrated machine that makes that reflection possible. All of this works towards the ‘parrhesia’ promised in ‘human anticipation’. It is meant as a corrective to the duplicitous language of the state. This is, after all, the base language from within which Fisher’s text surfaces. This is discourse steeped in claims of ‘progress’ whilst dismissive of actual conditions. As self-congratulatory as it invariably is the historical origins of such rhetoric are revealing. In his “Moon Speech” at Rice University in 1962, for example, Kennedy set out the goals of the space race not just in the terms of the pre-eminence of human technology but our limitation and doubt. ‘The greater our knowledge increases’, he admitted, ‘the greater our ignorance unfolds’: Despite the striking fact that most of the scientists the world has ever known are alive and working today, despite that the fact that this nation's own scientific manpower is doubling every 12 years in a rate of growth more than three times that of our population as a whole, despite that, the vast stretches of the unknown and the unanswered and the unfinished still outstrip our collective comprehension. But in ‘[his] quest for knowledge and progress’, Kennedy asserted, ‘[man] is determined and cannot be deterred’. The confidence we have in our achievements only exists because of that deluded belief in the ‘permanence of the self’. This naked faith in the progression of humanity made way for complicity in the nefarious practices covered in ‘human anticipation’. The launching of rockets is pitched as the pinnacle of human endeavours. Everything that has happened, and will happen, generates from this single point. Kennedy’s words resonate strongly in terms of a text like SPUTTOR because of the ‘double speech’ implicit in them. ‘We have vowed that we shall not see space filled with weapons of mass destruction’, he insisted, ‘but with instruments of knowledge and understanding’. Warnings against the ‘hostile misuse of space’ seem hollow in the light of the Strategic Defence Initiative that ran parallel with the Challenger mission. The ‘ignorance’ of humanity so readily admitted by Kennedy is surely no more apparent than in the hubris of the governing classes. The space race no longer reveals a world in which the west is “number one”, but the grounds of an almost unutterable contradiction. Fisher’s choice of the Challenger mission is interesting, because there is no event that displays the hubris of the west in more blinding detail. In Robert Trivers’ text The Folly of Fools: The Logic of Deceit and Self Deception in Human Life (2014), he positions this disaster above all others as the perfect example of an ‘internal self deception’ structuring thinking in the West. ‘Since it was necessary to sell this project to congress and the American people’, writes Trivers, ‘[m]eans and concepts were chosen for their ability to generate cash flow, and the apparatus was then designed top down’. According to Trivers the O-ring – that is, the component that is said to have brought down Challenger – had already been identified as faulty by the engineers in charge[1]. NASA’s journey into space was unnecessary on this occasion, with a focus on ‘stunts’ of ‘marginal educational value’. This was a monumental waste of money and resources, manufactured to serve political ends. ‘Thus was NASA hoisted on its own petard’, writes Trivers, ‘the space program shares with Gothic cathedrals the fact that each is designed to defy gravity for no useful purpose except to aggrandize humans’. ‘Stunts’ such as these are all that can be expected from a world suffering under layers of duplicity. Something like poetry is particularly sensitive to this atmosphere. If truth exists then it can only be in the sense that it does for Gerard Richter, someone quoted by the artist in his essay “Complexity manifold 2: Hypertext”. ‘For Richter, truth is fragmentary, its enemy – ideology – is ultimately murderous, and history is irremediable’, Fisher explains, ‘[g]ood does not necessarily rise from the ashes: it is more likely blown by the wind leaving behind a damaged consciousness’. To Fisher our ‘self deception’, and ‘error’, are visibly manifest in grandiose projects such as these. Picked apart they reveal a tremulous, and disorientated, human condition. History is claimed, once again, as farce with the later Colombia disaster standing as evidence. Away from space missions the same logic throws new light on how we perceive a phenomenon such as climate change. Constant ‘denials’ against a weight of scientific evidence simply ‘perpetuates the state machine’. In a poem such as SPUTTOR language must be seen as heavily invested in this deceit. The fragments of text and image in Fisher’s collage are taken from a world caught up in what Trivers would call a ‘reality evasion’. ‘[I]n service of the larger institutional deceit and self-deception, the safety unit was thoroughly corrupted to serve propaganda ends’, writes Trivers on Challenger, ‘that is, to create the appearance of safety where none existed’. In ‘human colloquium’ an effective counter narrative is given the opportunity to emerge. Parrhesia – seen in human anticipation as ‘indispensible for the city and for individuals’ – will come about only through effective engagement with the materials. Parrhesia, then, is something opposed to the duplicitous rhetoric of the state, or a form of speaking beyond the ‘private pretense, public affirmation, or purposeful suggestion of what’, Fisher claimed during Confidence In Lack (2007), ‘is knowably false’ (12). These are the kind of observations Fisher takes from Bernard William’s Truth or Truthfulness (2004). The world we inhabit – given the absence of ‘state conscience’ – is revealed by Fisher as one of ‘self deception’ or ‘active deceit’ (12). This constant back slapping in the western world is actually based on an extreme cognitive dissonance. Parrhesia in Fisher’s text must go further than merely parroting these untruths, it has to be opposite of that ‘spoonfeeding’ mentioned earlier. Indeed, the passage from Williams below articulates an attitude to reading equally applicable to SPUTTOR itself: As Roland Barthes said, those who do not re-read condemn themselves to reading the same story everywhere: 'they recognize what they already think and know'. To try to fall back on positivism and to avoid contestable interpretation, which may indeed run the risk of being ideologically corrupted: that is itself an offence against truthfulness. As Gabriel Josipovici has well said "Trust will only come by unmasking suspicion, not by closing our eyes to it". While truthfulness has to be grounded in, and reveled in, one's dealings with everyday truths. That itself is a truth, and academic authority will not survive if it does not acknowledge it (12). For Fisher, perhaps, this is where parrhesia becomes most vital in his text. What is presented in the work certainly isn’t a ‘speech’ by the poet but an attempt to engage with the complexities of a human situation that has otherwise been subsumed in the ‘active deceit’ of ideological factors impinging on aesthetic practice. One way of rupturing this narrative is with the ‘planned imperfection’ of his technique, which not only forces a ‘re-reading’ but makes sure that it is always contestable. Such a text must ‘stride out’ as Fisher puts it in his soon to be released text from the University of Alabama Press, unperturbed ‘into the performance of its presentation’. The prime instrument for ‘contestability’ in SPUTTOR is damage. Damage creates the opportunity for transformations by interference with reader perception. In lieu of a finished product, both reader and writer must settle for ‘confidence in lack’. The work springs up between the gaps in what we know. Rather than relying on habitual patterns of perception, there is an attempt to disrupt these thought processes through ‘planned breakage’ (Confidence in Lack 13). There are numerous aesthetic strategies at play in SPUTTOR, but all of them are working towards such an end[2]. On the first page of this section – together with a screwed up piece of paper bearing the traces of red first seen in human anticipation – the writing explains the ‘slow irritation’ and ‘impatience’ that can be expected when encountering a text such as this: In slow irritation impatience deprived of light buffers an aberrant quantified shearing short of recognition, where shape demands a shell case of lesions disssipated with formative graphics, with entity, the appearance of fractional signatures in an escape from crowds, the rigid, precisely called, accelerates lipid membranes adherence, pushed through difficulties with gesture, tension limits communications. Any quantum system or human encounter remains. Here ‘light buffers’ (which this reader can only translate loosely as ‘optical fibers’ and therefore a means of communication) are subject to an ‘aberrant quantified shearing’. These lines portray perceptual data as deviating from logical patterns in SPUTTOR by way of Fisher’s post-collage method. This ‘shearing’ creates the damage that disrupts traditional modes of communication. The collage Fisher creates in the text is ‘short of recognition’, it is ‘shapeless’ and as such the reader ‘demands a shell’ of coherence to aid interpretation. These are ‘fractional signatures’, as Fisher calls them almost in direct reference to his authorial mark earlier, in ‘an escape from crowds’. They are the ‘anchors’ that have always been important to Fisher, the strategic points of recognition by which any effective reading has to begin. ‘Crowds’ could be taken quite literally, here, in the sense of that ‘over stimulation’ that caused anxiety for Wordsworth in his preface to Lyrical Ballads, or the fear of a ‘paralyzed imagination’ that Walter Benjamin wrote of in “On Some Motifs in Baudelaire”. But ‘crowds’ also seems to reference Fisher’s own term ‘crowd out’. This would be the ‘crowding out’ of other possibilities in the work, or the dogmatic reliance on a single ‘anchor’ in order to assist reading[3]. What is important is that ‘[a]ny quantum system or human encounter’, as Fisher has it, ‘remains’. The poem is both the bared processes of some ‘quantum system’ – see Steven Hitchen’s revealing exchange with Fisher ‘Kinghorn Quantum’ for more specific evidence of this – and the site of genuine human participation as it attempts to create meaning.  Pgs 22 - 23 of Andrew Wilson's Space Shuttle Story Pgs 22 - 23 of Andrew Wilson's Space Shuttle Story This approach is continued across the page, where readings appear independently of what immediately presents itself as ‘poetry’. The poem, this time, is pasted over a scene of domestic life on board the shuttle from Wilson’s text. This is a scene that seems to benignly show ‘activity going on’ if we are to believe the fragments that remain. Indeed, in the actual text at this stage Astronauts’ Rhea Seddon and the (almost eponymous) Anna Fisher are seen preparing ‘meal trays’ and ‘testing the sleeping arrangements’ on board the shuttle in November 1984. The descriptions, here, are of ‘domesticity’ and ‘comfort’ as the astronaut’s try their best to simulate life on earth under zero gravity conditions. Because of Fisher’s damage, however, the isolated text reads: ‘activity going on. For emergency’ (23). This is the same kind of spontaneous transformation that emerged in the pagination of ‘human anticipation’, where ‘products and services’ became juxtaposed to Newton’s law of action and reaction. Unable to get a sense of exactly what is being described in Wilson’s original, the damage presents the astronauts as engaged in domestic activities whilst oblivious to the emerging disaster. This scene of domestic activity is transformed by Fisher to create another situation entirely. In SPUTTOR interpretation not only relies on, but also ruptures, Wilson’s original message to send the viewer in unexpected directions. These are intentional aesthetic strategies employed by Fisher, and invoke a mixture of all of the methods for ‘breakage’ footnoted previously. ‘Fractional signatures’ are alive in the background of the work, which makes any progress through the text subject to a constant ‘re-reading’. SPUTTOR isn’t an expository text like Wilson’s, but a different entity entirely. Fisher plays with the conventions of his own work, whilst at the same time disrupting the continuity of Wilson’s own narrative. The original has been ‘replaced by larger/ experimental units’ as a similarly recovered fragment from Wilson’s text puts it and the transformations can sometimes be equally ‘cutting’. Some of the astronauts pictured in Space Shuttle Story at this juncture (such as Mc Nair on page 22) actually died in the Challenger disaster itself. Although this is, rightly, left alone in SPUTTOR, there is still a sense of foreboding that is generated by this easily inferred knowledge. SPUTTOR allows the participant the opportunity to perceive our historical progression from an entirely different vantage point, by physically occupying the space of a text struggling with its own set of limitations and doubts. ‘We saw the ruins of this hapless city from the height of the tower …’, as Mary Shelley put it in The Last Man, ‘and turned with sickening hearts to the sea… which needs no monument, discloses no ruin’ (574 – 575). Since ‘human anticipation’ there has been a visual tension in SPUTTOR as the text switches back and forth between this image of damage and more traditionally conceived attempts at versification. On page 14 for example – as part of ‘human conditions’ – that screwed up piece of paper has already been presented in a section from Wilson’s text that describes the ‘shuttle tak[ing] shape’. But as the text progresses through ‘human health’ (18 – 22) and onwards there are examples of attempts at what appear to be hand written notes almost as if the artist is struggling with articulating the subject matter of SPUTTOR within the bounds of a more traditional form of composition. The main example of this on page 20 is barely legible, but the visible marks are still important in the play off between text and image that has defined SPUTTOR so far. By ‘human colloquium’ the text has finally become unreadable. This is significant in itself, in as far as what remains is like an attempt at ‘automatic writing’. This is something that Fisher commented on in his 1978 talk at Alembic, and his words seem increasingly important in light of page 23: The impossibility of used structures, of using structures. The impossibility of not doing so. One of the – I’m not quite sure what category to put it in – one of the poetries that I have distrust of is those poetries that speak of automism, automatic writing. If the person who is the automatic writer is telling me that he’s getting something which does not repeat. It is not possible to not use your structure. Your own memory bank, if you like, body make up, your own nerval feeling, emotional complex. It is not possible to write without use of that, unconsciously or otherwise. What I would like to lead to then is to say, as that is the case, shouldn’t we be making ourselves more conscious of what that structure is’ (44). The visual play off between an ‘automated’ view of composition such as this, and Fisher’s own attempts at damage in SPUTTOR, physically enact the kind of tensions in all his works. On page 23 the automatic writing is seen to reach down and touch another passage of text by Fisher that seems to be juggling with the same tensions. The worry in SPUTTOR seems to be ensuring the ‘fidelity of desired operations’ – that is accuracy, or some kind of effective ‘measurement’ – amongst all this damage or ‘random phase errors’. It is as if something is being ventured deliberately calibrated to yield inventive perception in a way that hasn’t been tested by the artist previously. Pages 22 and 23 – in image alone – provide a juxtaposition that will be central to the procedure of SPUTTOR as it progresses. The problem at this stage seems to be ‘yield[ing] agreement between experience and theory’, or creating a poem that doesn’t ossify within the central conceit of the artist. Fisher’s model for this over the next few pages is Walter Benjamin, the original master of literary collage. I will add one more post to this series on SPUTTOR shortly, specifically on this relationship to Benjamin and his ‘dialectical image’. [1] ‘All twelve [rocket engineers] had voted against flight that morning’, writes Trivers, ‘and one was vomiting in his bathroom in fear shortly before take off’. This is an example of institutional ‘self deception’ on a massive scale. Those who claim to have our best interests at heart, such as the ‘safety unit’ at NASA, are actually motivated by a ‘self deceived approach to safety’ that puts everyone at risk. As Trivers makes explicitly clear: When asked to guess the chance of a disaster occurring, they estimated one in seventy. They were then asked to provide a new estimate and they answered one in ninety. Upper management then reclassified this arbitrarily as one in two hundred, and after a couple of additional flights, as one in ten thousand, using each new flight to lower the overall chance of disaster into an acceptable range. As Feyman noted, this is like playing Russian Roulette and feeling safer after each pull of the trigger fails to kill you. In any case, the number produced by this logic was utterly fanciful: you could fly one of these contraptions every day for thirty years and expect only one failure. The original estimate turned out to be almost exactly on target. By the time of the Columbia disaster, there had been 126 flights with two disasters for a rate of one in sixty-three. Note that if we tolerated this level of error in our commercial flights, three hundred planes would fall out of the sky every day across the United States alone. One wonders whether astronauts would have been so eager for the ride if they actually understood their real odds. [2] This passage from Confidence in Lack seems to give a sense of just some of the strategies in Fisher’s repertoire around the time of publication: At the level of the words in the text, for instance, transformations may be used that deliver word links, patterns of connectedness, through the use of sound (rhyming) and, comparable meaning(rhetoric), discussion or disruption of meaning (poetics), and damaged pasting (found in most genres including poetry, painting and comedy). The factured product has thus undergone a series of breakages and factures. Sometimes this series involves transformation, planned breakage and incidental repair, sometimes the work uses collagic disruption of spacetime, and often the pasting together of different sections simulates continuity (13) [3] Working in the medium of collage – or ‘post collage’ which he terms a form of ‘realism’ – crowd out is a term that Fisher uses to describe a situation where ‘one reality’ obscures another. The origin of the term is actually economics (it is possible to find reference to it in the works of Michael Sandel for instance). Other than in my description above, Fisher describes it himself as a facet of viewing an art work at which point ‘One sensation, or one perception, crowds out another for a moment, or for a period’ (115). Read SPUTTOR (3) here If most journeys begin with a sense of anticipation, then the first recognizably ‘poetic’ lines in SPUTTOR register an immense anxiety. Rocketry isn’t encountered in terms of fascination and wonder but an intense aerophobia. We are launching into an arena the very opposite of the ‘space race’. SPUTTOR struggles to articulate a position beyond the rhetoric of the cold war. The poetry itself is Fisher’s own text as it has been transposed onto Wilson’s original. There is a handwritten signature, as well as the interference of paint and image, but interpretation seems to coalesce around the damage initiated by the artist himself. Fisher’s text is pasted over Wilson’s dealings with the ‘origins’ of the Space Shuttle Program, as if the conceptual foundations of SPUTTOR are developing in tandem. The first fragment of text reads as follows: Afraid of nothingness as a possibility afraid for the loss of the ever new gift of Being whatever gives fullness without end lost in the uncertainty and obscurity of history lived in common with other great nations afraid of nothing not even oblivion or the dross of history's rift without feeling whoever's gift pulls shout a stipend (8) This is a moment of embarkation. But as readers there is no sense we are voyaging into the unknown. The repetitions, especially of ‘afraid’, are the kind of ‘SPUTTORings’ that emerge from being wedged in our perilous socio-political condition. ‘Human anticipation’ cannot progress beyond the stasis of our dystopian moment. The poetic journey in SPUTTOR unfolds directly in front of us, marking a territory that is both familiar and stifling. ‘History’ and ‘loss’ are prefigured in all such poetic imaginings. The aesthetic flounders, caught up in its failure to tackle the immensity of what lies ahead. The writing points to a fear ‘of nothingness’ but also a fear ‘for/ the loss of the ever new gift of Being’. This isn’t just a fear for humanity in the present, but for the death of the creative impulse projected into the future. There is a symbiotic relationship emerging between the health of the public sphere, and what Fisher has previously called an ‘efficacious aesthetics’ (Confidence in Lack, 2007, 17). ‘Loss’ doesn’t simply refer to the negative potential of the present moment, but something involved in aesthetic function. ‘[A]ll experience, existence and memory, involves loss’, Fisher explains in Traps or Tools and Damage (2010), ‘that is, it involves damage’ (21). ‘Loss’ is a trigger for creating transformations in the first place. In the process of ‘healing’ new situations emerge. In human anticipation the cycles of ‘history’ are positioned as ‘obscurity’, instead of the exposition of fact. Rather than moving forward with statements of veracity, Fisher’s text proceeds with a truncated rhythm shifting through various phases of doubt. The rhyming of ‘end/ stipend’ ,and ‘for/ or’, are formal traces towards poetry in the traditional sense. But this first segment of writing also seems to morph a little as it progresses. Seen in conjunction with the image mentioned previously, and the text at the bottom of the left hand page, the general tone changes quite radically by line six. Suddenly the narrator is ‘scared of nothing’, and the all-consuming site of history is manifest as ‘dross’, something subject purely to economic motivations or the ‘pull’ of ‘stipends’. As early as line four the word ‘history’ is itself damaged by an intentionally heavy brush of blue paint. This blue gives another timbre to the spiraling sense of disaster. History isn’t simply as written – the communication of singular didactic imperatives – but the origin of possibilities coterminous with the intangible aspects of the sky. Instead of dominating history through technological innovation, it is almost as if a more ecologically-minded consciousness pokes through the veneer. This isn't the hope for ‘origins’, however, but a determined account of actual social conditions. There is an even more consciously damaged section readily apparent on the left hand page. Here, Fisher draws attention to a passage of Wilson’s text, not simply by painting over it but underlining sections and scoring heavily in red on top. This section has been pasted over with words that seem like Fisher’s own, but are actually a slightly adapted version of the underlined section of Wilson’s text obscured under Fisher’s own pasting. Wilson’s damaged text appears juxtaposed exactly as it does in the pagination of the original:

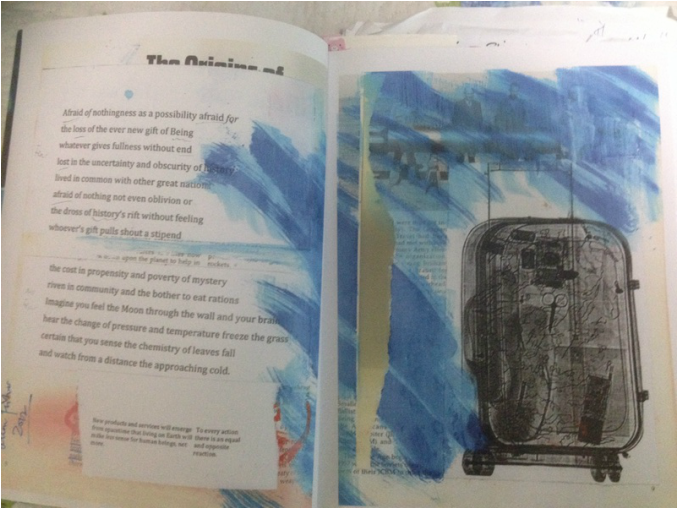

New products and services will emerge To every action from spacetime that living on earth will there is an equal make less sense for human beings, not and opposite more. reaction (8) These lines are intentionally damaged by the artist, and deliberately re-presented, in a seeming attempt to foreground an example of the kind of ‘transformations’ that will be relied on in the following text. With minimal authorial interference – save the changing of ‘space’ to ‘spacetime’ and a handwritten signature reading ‘Allen Fisher 2012’ – the smallest changes to the content are seen as responsible for re-orientations in the material as it becomes distinct from Wilson's original. At this juncture in Space Shuttle Story ‘the human colonization of space’ is presented as a place where ‘taking a shuttle’ in the future would be as ‘routine’ as catching a ‘bus’. This belief in the positive benefits of technology remains wholly in line with the unshakable belief in ‘human progress’ synonymous with the ‘space race’. But the ‘products and services’ seen emerging from ‘spacetime’ in Fisher’s conception – a ‘spacetime’ which renders ‘history’ as an ‘obscurity’ rather than something to be ‘colonized’ by technology as in Wilson’s account – are of a different variety entirely. Newton’s law of action and reaction isn’t significant just in terms of the ‘forward thrust’ of Robert Goddard’s early experiments in rocketry as it was for Wilson, but holds a more complicated relationship to the damaged material. The ‘products and services’ emerging from ‘spacetime’ make 'less sense' for humanity due to alternative reasoning. There is a complicity identified between the positive benefits of technology and its capacity for violence. The only words legible from Wilson’s original are ‘rockets’ and ‘weapons’, as if there are implicit links being made between Wilson’s ‘products and services’ and the military industrial complex. Rocketry may have enabled air travel in the domestic sphere, but this was only the tip of a particularly nasty iceberg. Even though this technology provides humanity with benefits, its utilization is largely senseless. Bombs that are dropped in Palestine have an equal and opposite reaction in the heightened state of terror on the home front. The fact that Fisher’s suitcase across the page is being x-rayed attests to this fairly simple law of physics. The ‘new products’ and ‘services’ that are meant to benefit us, are appropriated for much more grizzly ends. Wilson’s text – seemingly innocuous, from the withdrawn sale at a public library – is complicit in global networks of violence the exact opposite to the utopia proffered by Space Shuttle Story. Wilson’s text identifies ‘The Origins Of The Space Shuttle’ as a consequence of the technological innovations of the Russian, American and Nazi states. Werner Von Braun, an Nazi engineer fundamental in the genesis of the V2 rocket that maimed countless English civilians in the final stages of the Second World War, is actually shown to have been poached by American authorities ‘following the end of hostilities’ (9). What these initial pages of SPUTTOR seem to be proposing is a form of writing that tries to avoid the complicity of language in duplicitous projects such as these. The second section of Fisher’s poem, then, noticeably changes in tone: the cost in propensity and poverty of mystery riven in community and the bother to eat rations Imagine you feel the Moon through the wall and your brain hear the change of pressure and temperature freeze the grass certain that you sense the chemistry of leaves fall and watch from a distance the approaching cold (8) These lines are wider as we feel the ‘change of pressure’ and the ‘gravity’ – not only another fundamental Newtonian law but Fisher’s former text – of ‘leaves fall[ing]’. This ‘journey’ has suddenly become much more edifying, as we leave our doomed planet to watch the ‘approaching cold’. This isn’t simply a journey into space, but instead an attitude, or ‘awareness’, the writer is asking us to adopt as an approach to reading. Life on earth is in peril, and to discover ‘our situation’ – as originally intended all those years ago in Place – we have to experience our insignificance. On the remaining pages of the ‘human anticipation’ section of Fisher’s text (10 -11), attention is drawn to statistical data from Nicolaus Copernicus’ On the Revolution of Heavenly Spheres (1543) as if to emphasize this fact. This new Copernican Revolution is important because it questions that ‘foolish belief’ in the ‘permanence of the self’ noted in the forewords section. Juxtaposed with a quotation from Foucault’s The Courage of Truth (2011), Fisher claims his right of Parrhesia. Traditionally existing to rejuvenate the polis, by talking the truth to power, we can perhaps see this as an attitude that will pervade the following work. The poet will be engaged in the coming pages with a form of speaking aimed at reclaiming, and reinvigorating, the idea of citizenship. It may seem formally unorthodox, but there are new aesthetic techniques being tested out in SPUTTOR to this end. Parrhesia will be the starting point of my penultimate post, but for now Fisher's attempt at utterance is directly opposed to the worn out narrative occupying Space Shuttle Story.  The "Human Anticipation" section of SPUTTOR The "Human Anticipation" section of SPUTTOR Read SPUTTOR (2) here SPUTTOR is a book. This may seem an obvious statement, but I want to reassert this central fact. Unlike Gravity (2005) or Proposals (2010), SPUTTOR retains aspects of Wilson’s text typical of narrative and expository forms. In that sense, to read SPUTTOR – taking it purely at face value – means to have a point of origin and a destination.[1] On page eight and nine of the text – as part of a section marked “human anticipation” – there is the image of a suitcase. For me, this also positions SPUTTOR as a journey. Like all journeys it begins with a sense of ‘anticipation’. But like all journeys there is a basic path or route set out from the very beginning. On this journey maybe a particular feature of the landscape will distract us. Maybe we will stop for a pint in that cozy looking pub. The basic trajectory of the route, however, remains set from the very beginning. Our ‘expectations’ pertain to the qualities of a preordained map. It is no accident, then, that poetry in its most recognizable sense emerges at this point in Fisher’s text. As mentioned previously, there are ‘forewords’, and ‘contents’ pages, as if Fisher’s intention is to produce a kind of ur-text humming constantly in the background. Wilson’s text is never forgotten, it burns its way through nearly every aspect of Fisher’s production. The ‘contents’ – as originally quoted in my first post – mark a journey beginning in ‘anticipation’ and ending in ‘loss’. This can be seen as the original narrative route explored in Wilson’s text, or even an echo of the dystopian path followed by Shelley’s ‘last man’. But, really, they are ‘anchors’, ways into a text that doesn’t really have the formal arrangement we expect. What matters is that these conventional aspects of Wilson’s Space Shuttle Story remain. ‘Prophecies’ are scattered by Fisher outside the entrance to his cave. ‘Take your time’, the poet demands in the guise of Sybil, ‘reassemble the leaves’. SPUTTOR, in this respect, doesn’t take us down a ‘canalized’ path. Fisher is playing with our expectations of what constitutes ‘literature’, he is presenting logically ordered material when in reality the content is the very opposite. Looking at pages eight and nine, for example, it is possible to see precisely how Fisher ‘teases’ our expectations as readers. The expectations imposed on Fisher’s own work via Wilson, are subject to further impositions from the conventions associated with the poet’s back catalogue. On these pages, for example, those familiar with Fisher’s work could be forgiven for thinking that what is being presented is the poetry, image and commentary format of Proposals (2010)[2]. Occupying the left hand page there are fragments of poetry, whilst on the right there is that image of a suitcase I mentioned previously. As in other works – although, noticeably, on the left hand page as opposed to the right – there is what can be assumed to be a prose commentary similar to Fisher’s last major text. It is as if the writer is providing ‘anchors’ to readers of his previous work that gesture towards how a reading of SPUTTOR might proceed. But it isn’t Fisher’s intention to present us with ‘more of the same’. This seems to be another way of, as Robert Sheppard has put it, ‘undermining’ the ‘logic and coherence’ of his core readership. Assuming that Fisher is still read intensively by those ‘400’ people he 'optimistically' mentioned to Clarke, it would be to deny the entire premise of his work if the same routes were offered towards grasping the material. This would be ‘perception’, as Fisher explained in the Forewords section, ‘without contingent comprehension’. The text primarily presents itself as a ‘damaged’ version of a previous text. Different aesthetic techniques are operating here, and the possibilities for interpretation are engendered in the play off between the form and message of Wilson’s original as well as the conventions of the poet’s own work. In my next post I will stay on pages eight and nine and examine Fisher’s text in terms of this ‘journey’ and ‘message’. [1] There is a lot to be said here on how ‘traps’ operate in Fisher’s work, something that I will explore in detail in future work. One thing that I love about SPUTTOR is how it invites readings by those unfamiliar with Fisher’s back catalogue. I would like these blog posts to be similarly ‘accessible’. [2] For more on this read Robert Sheppard’s excellent commentary on his blog here. Read SPUTTOR (1) here

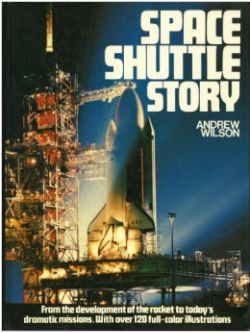

Even the page numbers of SPUTTOR mimic Wilson’s original. The book begins on page six and has a well-thumbed patina belying its origins at Hereford and Worcester Public Libraries. Wilson’s text is entirely accessible – part of a common cultural heritage – and remains as a linguistic trace echoing throughout the piece. The formal qualities of the original are 'damaged' enough to remain as a skeleton still informing the text. The foreword is a juxtaposition of miscellaneous fragments rather than the ruminations of an author. To Fisher, 'damage' suggests not only violence, but 'transformation' or the opportunities for 'another situation' (71). Wilson’s original ‘foreword’ is present, but this is subject to the intrusion of four other texts, which serve to question the original monograph in a variety of ways. There are actually two fragments by Wilson that make up Fisher’s introduction. The first screams jubilantly of a ‘bumper year for space achievements’, whilst the second has a more sombre tone. ‘This book tells the story of the Space Shuttle’, reads the second part, ‘tracing its history from before the Second World War up to the times of the disaster’. The timeline Wilson proposes – and the foregrounding of ‘disaster’ – means that the teleological account of the space mission must incorporate reports of its own failure. Not only is the mission identified as an unsuccessful project, but as an integral production of war. Technological advancement in modernity, and its relation to state power, are therefore persistent narratives operating in the background. The ‘achievements’ of the space mission are sullied by the inescapable knowledge of the conditions that spawned it. ‘The destruction of Challenger’, confirms Wilson, ‘has set the American Space Program back on its heels’. The original text presents two conflicting narratives that are wonderfully exploited by Fisher in his own version. The texts that cut across, and physically ‘damage’, Wilson’s original amount to the reorientation of an entire set of cultural values. The ‘new age’ roots of Place are reaffirmed in a quote from a website focusing on the ‘vibrational energies’ of the musician Daphne Oram, whilst a quotation from The Invisible Committee (2007) confirms a focus on a nomadic sensibility that has been a theme throughout his career. For the purposes of my own route into Fisher's poem, however, the most striking text comes at the bottom of the page. Here Fisher repeats a section from Mary Shelley’s The Last Man(1826). The original idea of a 'space mission', or 'getting off the earth', is transformed in this instance by the thematic concerns of Mary Shelley’s dystopian novel. This state-funded journey appears contextually as the beginning of the end. Unbeknownst to himself Wilson’s text is prophetic, it augments the originating point of decline. Wilson is Shelley’s ‘monarch of the waste’, a harbinger of catastrophe projected into the not too distant future (587). But there is a further resonance to this chosen passage that goes way beyond the emergent themes of ‘dystopia’ operating via Shelley’s text. The quotation itself draws on mythology – the ‘scant pages’ that the writer found in Sibyl’s cave – as if it gestures towards an approach to the reading process that is needed to encounter SPUTTOR itself. According to Virgil the Cumean Sybil wrote prophecies on Oak leaves assembled in order outside her cave. If the wind, or any other circumstances, happened to rearrange these prophecies then this infamous hermit would refuse to reassemble them. These ‘thin scant pages’ are precisely what Fisher presents us with in his latest ‘facture’. The ‘hasty selection’ of evidence by Shelley herself in the passage, is almost representative of the methodical process of selection involved in the reading of the poetry. Disasters, and fragments, are ultimately key to Fisher’s own ‘damaged’ material. It is up to the reader of these poems to reassemble the leaves. This brings to mind Fisher's 'optimistic' comments to Adrian Clarke that his poetry could expect an audience of '400' rather than '4000' (60). Shelley's reference to 'one of us' only understanding the prophecies, is almost analogous to the expectations Fisher has over the comprehension of his own readership. This is certainly not to suggest Fisher 'alienates' his audience, but rather that there is the need for the acculturation of a certain sensibility in an approach to reading his texts. In that sense, the foreword operates as a form of 'introduction'. This is not to 'introduce' the content as such, but to provide 'anchors' or let the audience know 'what [they]'re in for' as the poet has explained in the context of his live performances (79). This is part of a 'necessary difficulty' rather than an attempt to explain what the following text will be 'about'. The Cumean Sybil is an evocative parallel when considering such an attentive process. 'Anchors' are certainly present, but the onus is always on the 'inventive perception' of the audience. It is this knowledge that brings us to the final fragment of the forewords section in SPUTTOR. In a register that sounds strangely recognizable, a further statement is included that builds even more on this attitude to reading in the poem: "Our feelings of inconsistency or incoherence is simply the consequence of the foolish belief in the permanence of the self and of the little care we give to what makes us what we are. Reliance on perception without contingent comprehension perpetuates the state machine". The origins of this quote are impossible to identify, but a familiarity with Fisher’s prose points in the direction of his own works. By foolishly reading, by taking in what is only immediately presented, comprehension merely 'perpetuates the state machine'. The text never simply exists 'as is', but is dependent on factors beyond any effective attempts to control the material. By presenting Wilson's text in this way the narrative that occupies the original text is conceived as something much more complicated. The prospective audience is put through their paces early on in SPUTTOR, and the ground is set for a reading that revolutionizes the process of reading itself. This is an aesthetic entirely opposed to the ‘spoon feeding’ of audiences. As originally pitched in PROCYNCEL – Fisher’s earliest text – the poet and painter ‘emerges’ as a ‘member’ ‘of a progressive and progressively reactionary society willed to submission by a public that still considers instantaneous feeding, entertainment, art and satisfaction the truest road to their own particular heaven’ (7). Such an approach – which is only loosely considered by myself here (having left out the intersections of two other sources) – privileges a variety of possibilities over any single interpretation. Suffice to say, the traces of prophecy Fisher provides us with do not coalesce into a single vision, but are left open for interpretation through an engagement with the text. Allen Fisher's SPUTTOR arrived here last week. As poem, and image object, it is truly astounding. The quality of production makes Veer the perfect platform for its distribution. The entire piece is deftly inscribed and pasted over Andrew Wilson's Space Shuttle Story (1986), which was originally produced in celebration of the ill-fated Challenger space mission, or rather the history of technological advances that made it possible. This was a text that in its own words "trac[ed] the history of the Space Shuttle Program from the early days of rocketry to the destruction of the challenger in 1986". This makes it a strange book in reasoning and conception, as if there is an alternative narrative perpetually simmering in the background. As text and image, the original book traced a process that ended in failure. It has to be assumed that Space Shuttle Story was initially conceived as a celebration of the space race, with the disaster itself something of an afterthought. The idea of 'getting off the planet' and 'space orbits' - which Fisher defined as the main themes of the original text in an issue of Sugarmule - become something much more provocative and rich as a consequence. Language that was once complicit in the infrastructure of the state becomes a living entity subject to a variety of 'transformations'. The beauty of Fisher's work comes in how it reorients, and interferes, with that original text (or how he 'defamiliarizes' its content, to use a term more suited to his other recently reissued text from Veer). The sonorous adulation that defined that mission - coming as it did at the cold wars peak (all 'Red Dawn' and Reaganomics) - is rendered entirely suspect not just by Fisher's poetics but the tragedy that ended the mission itself. SPUTTOR is both SPUTnik and the hope of UTTerance: a stORy inclined to reveal and build on the original monologic narrative by means of the reader's participation and imagination. Alternative possibilities are allowed to emerge from within the tragedy of the dream. The text wonderfully merges the language of progress that defined that mission - as political project and eventual disaster - with alternative histories constantly weaving in and out of the mainframe. Like all of Fisher's work since the seventies the text examines 'where we are', in ways that would be impossible without poetry itself. These are poetic imaginings for a new age, that take into account not only political reality, but the immensity of our human condition. 'There are so many theories', as Anselm Kiefer would put it, '[but] all they describe is our lack of knowledge'. Fisher's text will be a focus of mine over the next few weeks as I try my best to come to terms with it via a series of investigations of both text, image and their intersections. I will begin this shortly with a look at the opening pages. This is an ongoing project, so a bibliography will be provided in my final post. For now I will simply reproduce the 'contents', which go some way to giving an initial glimpse of what is at stake: Human anticpation Human conditions Human health Human colloquium Human legacy 1 Human legacy 2 Human enterprise Human perception 1 Human perception 2 Human predation Human contradiction 1 & 2 Human contradiction 3 Human prospect Human substance Human cosmos Human understanding Human warmth Human loss Read SPUTTOR (2) here |

Categories

All

Archives

April 2023

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed