|

This is the trailer for a new KBS documentary premiering next week in South Korea. As an account of the massacre it focuses on Daejeon and the key stories that need to be considered when accessing the truth of what Winnington witnessed.

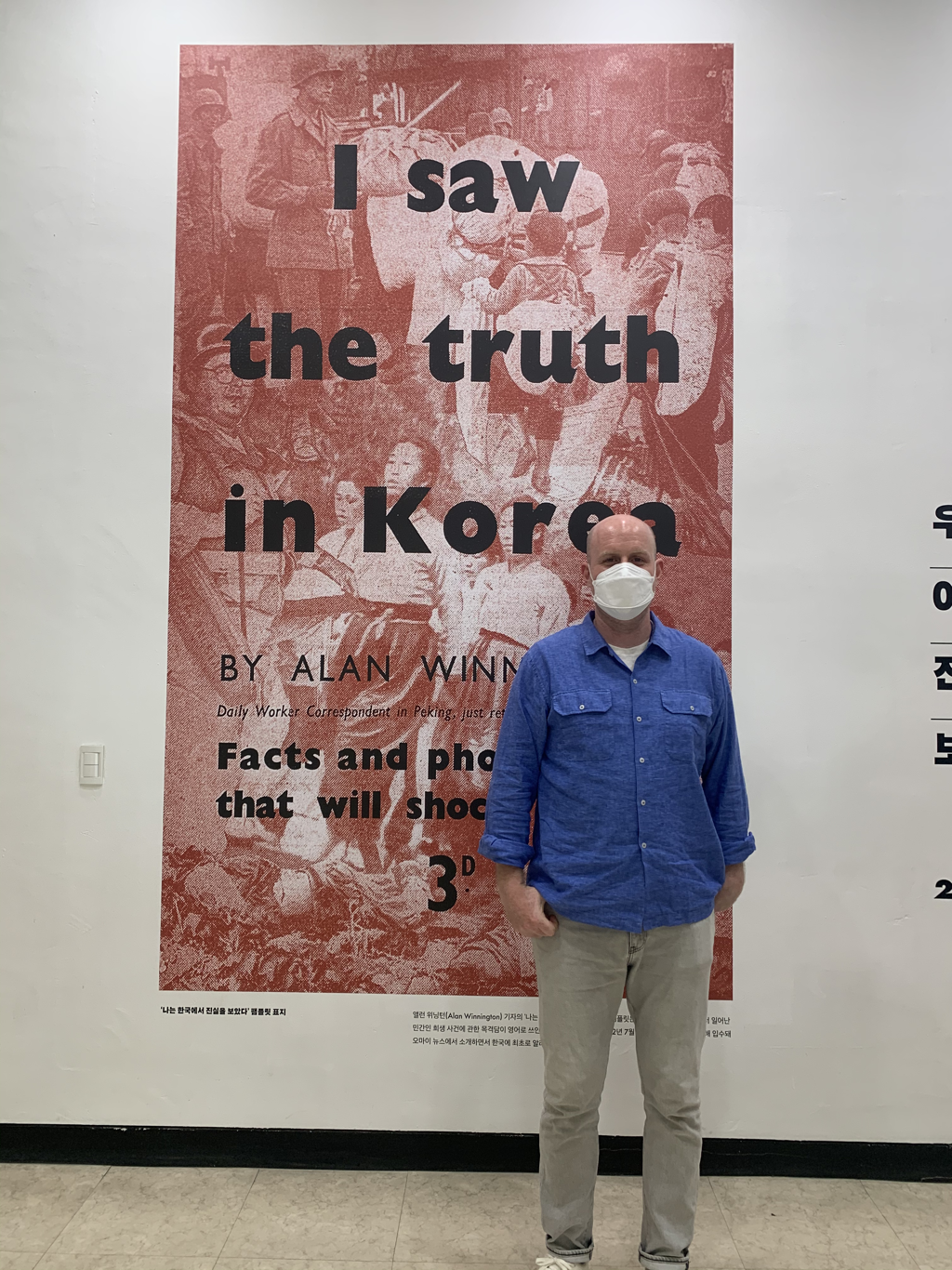

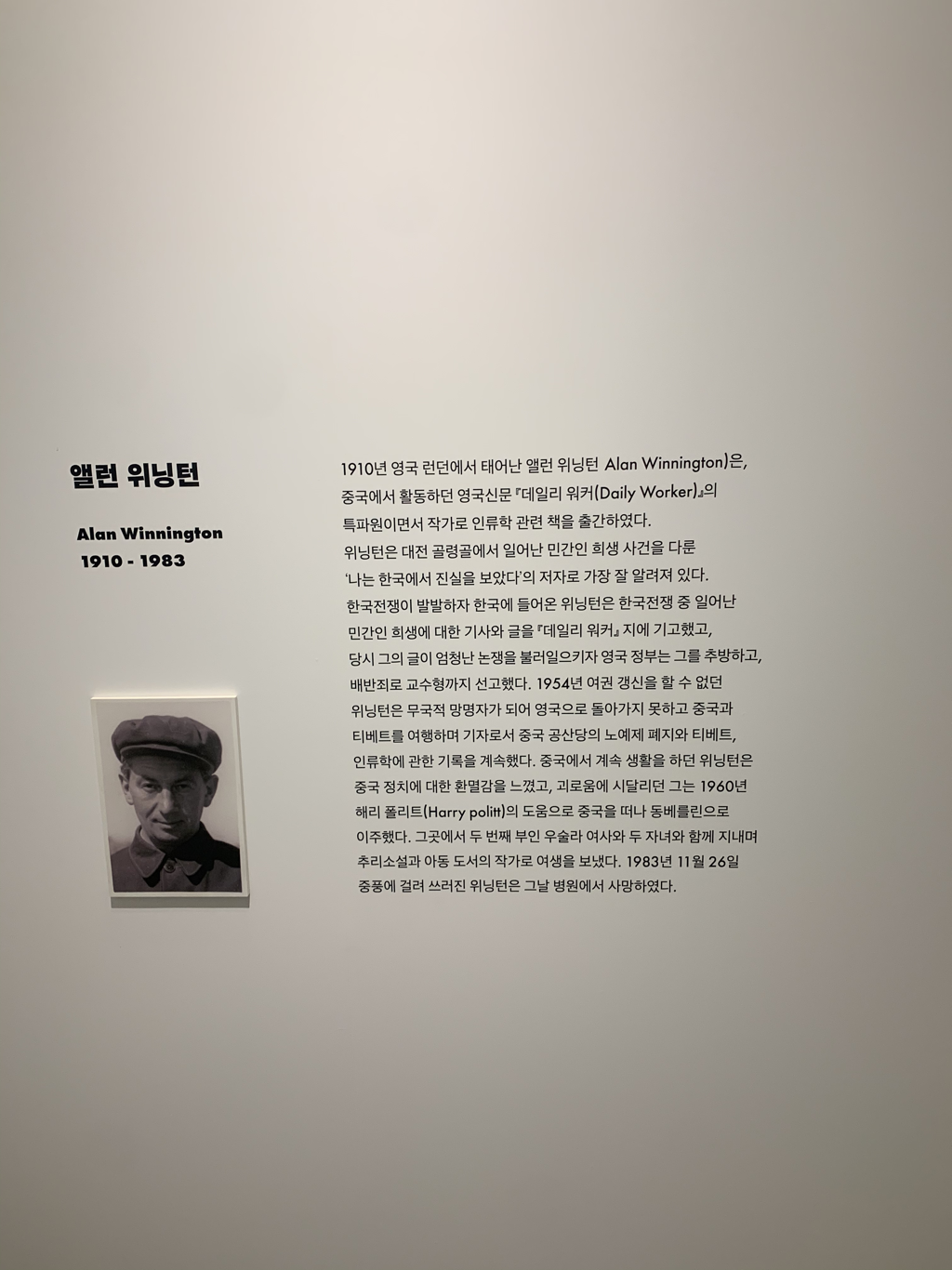

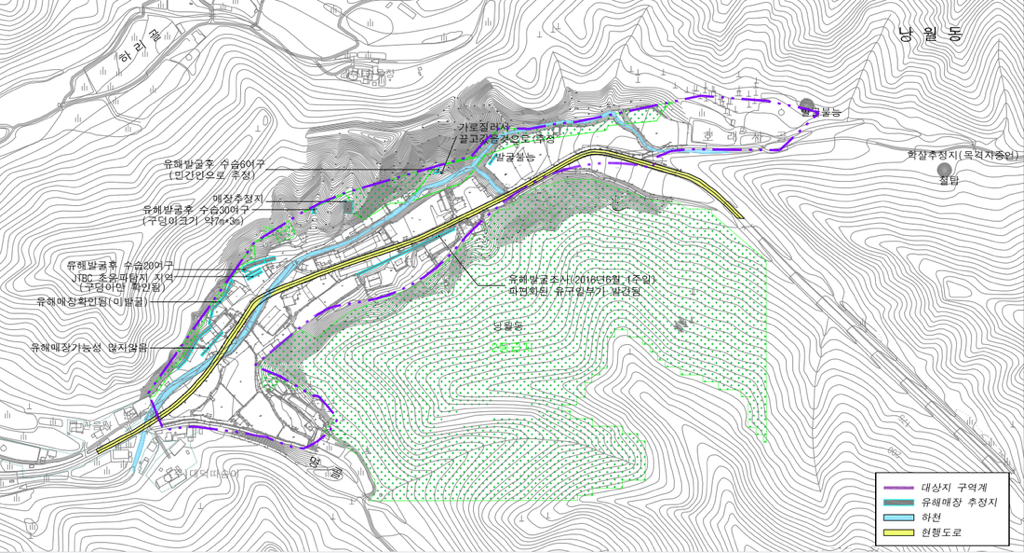

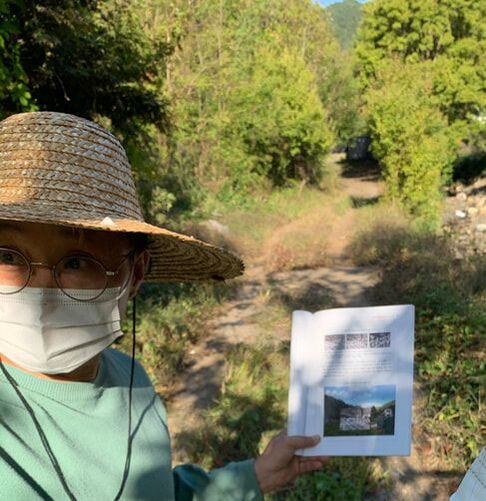

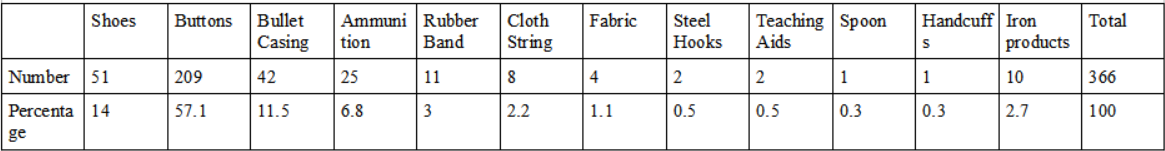

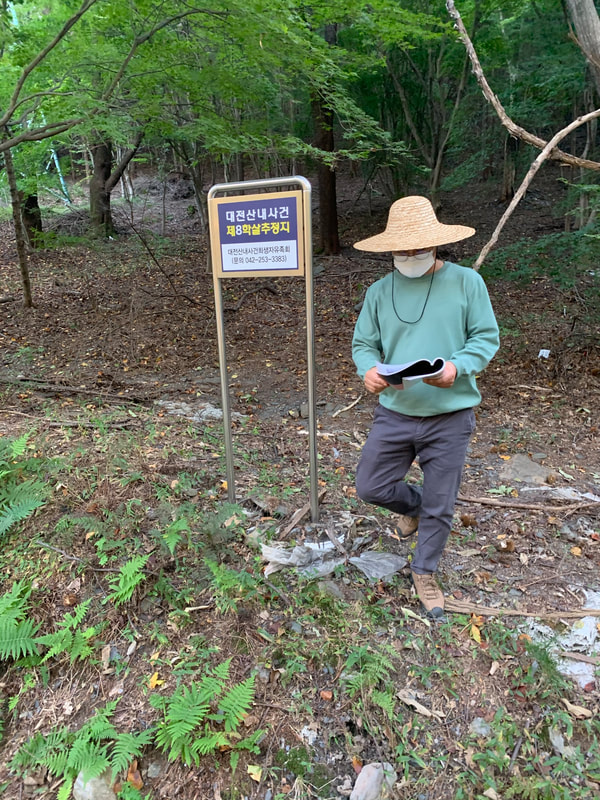

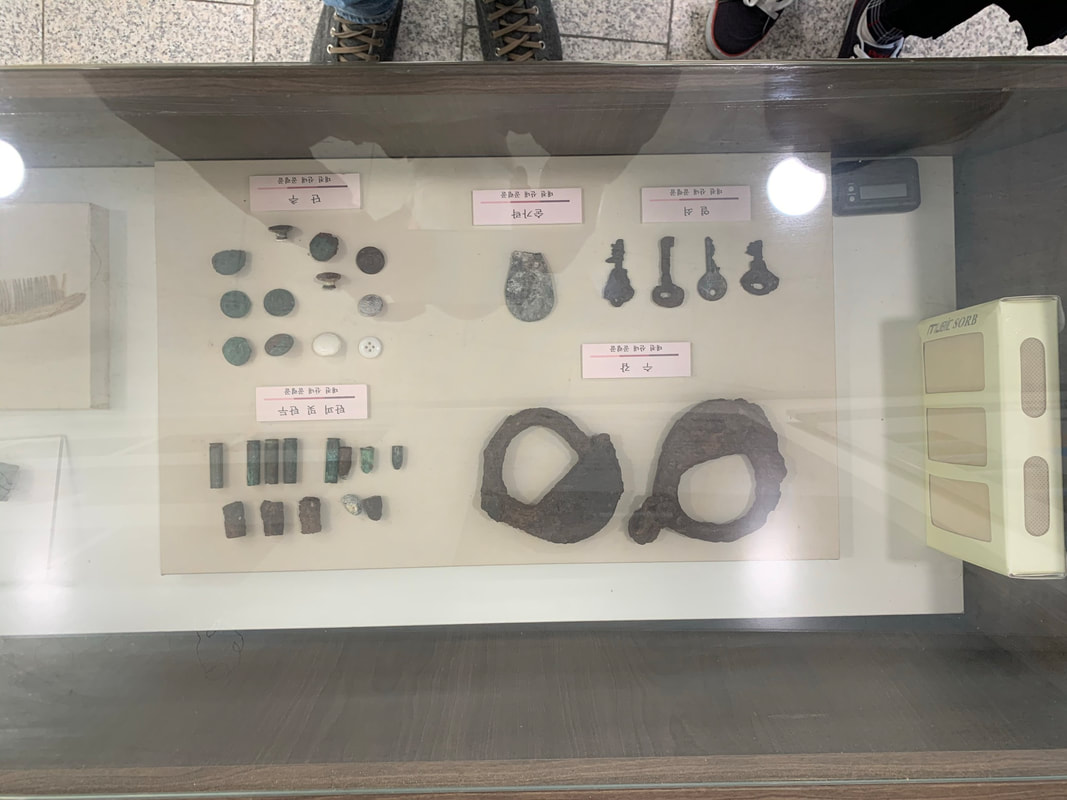

There is also a series of Newstapa documentaries focussing on these massacres at some point this year. Rather than just focussing on Daejeon these look at massacres throughout South Korea committed at the same time. I will definitely link to those in the future. One of these - in Gongju - is something I have been looking at in detail relatively recently. “Facts cannot be hidden forever... all we have to do is our share of getting the truth known” The above quote is taken from a letter from Winnington to the POW Andrew Condron in 1952. It still stands. So much is left over from the Korean War that is little understood or appreciated. This is why I wanted to be involved so much in this exhibition of Winnington’s photographs that opened today in Daejeon. It wouldn’t have been possible without the local council, and the amazing knowledge of local activists Shim Gyu Sang and Im Jaegeun. I could only contribute to the Winnington aspects of everything there. This was “my share”. I will continue to contribute for the same reasons wherever possible. Both because it is so necessary for a lasting peace in Korea. But also because Winnington himself is so misunderstood. Everyday there is new information that astounds me - and every day I am shocked by the consequences of what he witnessed. This excerpt from a “Cassandra” article in the Daily Mirror in 1955 is indicative when we consider the lies and misinformation that was spread around at the time. Not an attempt to “get the truth known” but to obscure it further. This is one of the main reasons we can only “s[ee] the truth” today. The exhibition will be open for ten days in Daejeon this week. At the 전통나래관 behind Daejeon Station (if anyone is reading this in Korea) In what follows I will recount a journey I made to the valley in Daejeon with the local journalist Shim Gyu Sang. I am making these posts to fill in the gaps for people who might be interested in the story of Alan Winnington, but also in the narrative that surrounds the Korean War in a much wider sense. Both are important because they are largely “inchoate” accounts that have accrued much complexity and misunderstandings over time. It makes sense to choose this particular word, because it is not that they are just “unfinished” but “unfufilled”. By which I mean these accounts lack context and closure. These posts are part of a collective attempt to truly understand what happened in the war and its aftermath. As a result they require attention to detail, and - as I've discovered recently - a spatial awareness that can evoke a sense of scale and experience. Similar things are true of Alan's “posthumous” autobiography published three years after his death. Both are narratives to which new information and context is constantly being added, and both are victim to prejudice and ignorance where the human element is rarely perceived in its full complexity. This is not about ideology, even if politics is inextricably bound up in what must be told. Instead these are stories about cruel cycles of history that care very little for political affiliation. As always it is people themselves who are disappeared in these partial attempts at retelling. So, again, I want to point to the “inchoate” status of these stories and events. At the moment it might be said that we are carefully assembling a mosaic, one of the most important parts of which is the oral histories that have been suppressed for so long. This comes with all the trauma these events still uncover, but also a curiosity at new discoveries. In the next few years I hope that this place, and the wider history surrounding it, genuinely promotes discussion. We have made much progress since looking into this in detail this year (most of which I will have to explain in the future), but every day brings new information it is hard to keep up with. At that level be aware that some of the things below may well be superseded in the future. We are continuing the excavations well into 2022 so this will inevitably be the case. In order to make this post I was taken on a tour of the site by Mr Shim in October. He is a genuinely inspiring person having written on this issue for over twenty years now. He has actually been following it for much longer, even when it wasn't safe to talk about it properly. Mr Shim is now an inextricable part of the discovery and reporting. His story is bound up with any goings on here along with those of another local journalist and academic Im Jaeguen. The enthusiasm and detail that Mr Shim provided me with during the exploration of the site was utterly boundless. His hospitality, and curiosity, are something I hope I can replicate albeit under much more favourable conditions. My mosquito scarred scalp and sunburnt body in October attested to the level of attention and effort that is still required to explore this site in full. I still smile when I think of Mr Shim squatting away snakes from site number three with a stick he had broken off a nearby tree. I hope that what is detailed below encourages more people to embark on a similar journey. Even if it is only with the information I have provided. The following, then, is a synopsis of the eight sites in the Daejeon Valley as they stand today. It must be remembered that these are only the ones that we know about. This does not mean that there aren't others. One of the most incredible things about dealing with Alan's primary sources is that the smallest detail can have huge implications for things on the ground in South Korea. Having seen primary sources by Winnington recently, as well as examining in detail his original reports, it is clear that much more could exist at this place that is simply unknown. All of the witnesses who lived here during the war have now passed on, and even Shim Gyu Sang had trouble getting them to explain their stories ten years ago. The only way it was possible – so he tells me – was to buy them makkolli and dinner and then drive them to the site where they would point through a closed car window at the mountain in the distance. This was out of a genuine, and completely understandable, fear of retribution by the authorities. I have included pictures of Mr Shim on our journey in the explanations. I should also mention that he soused me liberally in makkolli beforehand as well. Site One: Emmanuel ChurchThis is the site in Daejeon at which they are currently digging, although it will be extended to other areas in the future. Some recent discoveries confirm that people as young as fifteen were killed there, but also that (as Winnington stated in his original newspaper reports, and as has been confirmed since by witness testimony) many of them were women too. Both these facts are often omitted from official accounts, and it is important to restate them as often as possible. The distinctive aspect of site number one is the Emmanuel Church that exists on the site itself. Rather than being a longstanding construction it was actually built in 2001 illegally on land that should have been protected . This was simply an oversight by the local administration at the time, but it led to a protracted battle with the church that has only just ended through the compulsory purchase of the land. A lot of remains were discovered by the Bereaved Family Association as they stood by and watched outraged as the foundations were dug at the time. Shim Gyu Sang collected these in an old kimchi pot and buried them under the memorial stone that existed on site. At the moment of writing Park Sunju and his team have discovered 200 complete skeletons here, and this is only the very beginning of the process. In 2015 a test pit was completed where 20 bodies were found. After this excavation a raised earthwork was constructed on site in the shape that the pit is believed to follow, both as a memorial but also to point to the urgency of future diggings. It is at this place the final set of excavations will be ending this month. I am not sure it has been deemed wise to dig below the Emmanuel Church at the moment, but it is certainly being discussed as a possibility. Site Two: The Longest TombThis site is the one that gives the valley the name of The Longest Tomb in local mythology. In the two photos attached – I simply circled the camera from left to right where i was standing at the time – you can see the supposed extent (200 yards long according to Winnington) of the trench as it runs parallel with the new road built in the Sixties. It was thought to run from the pylon in the far distance to the house with the blue roof on the other side. New data, however, has shown us that this might not actually be the case. It seems that the residents of the valley confused the new road with the old one that existed at the time. I can't say much more about this at the moment, but the new excavations should be able to find the exact place of this trench due to the discovery of important photographic evidence This is the place where it was also assumed the construction company discovered a lot of remains when they were digging the road. Actually, Shim Gyu Sang traced this company a few years ago and they denied all knowledge of what went on at the time. It's only speculation, but it is most likely that rather than being “government interference” it was more to do with avoiding paperwork and delays to the project than anything else. But whatever happens, this place is a key area for excavations because of the size of the pit. Now that it has been located expect much more news in the future. Site Three: Truth and Reconciliation Commission ExcavationSite three is supposed to be the place where people in the collage made by Shim Gyu Sang earlier were killed after the two main massacre sites were filled in. This suggests that their killing was something of an afterthought, and they may have come from outside of Daejeon or were people who were captured further away. Because of the small size of this place it is quite unique. Apart from the identity of the people killed here lots of information has been found out. In fact, in the councils own list of excavations in the valley it is the only site that is labelled “done”. These days it is extremely inaccessible and is the place that Mr Shim used his stick to remove unwanted snakes and spiders. As can be seen from Mr Shim's demonstration below the way in which these people were killed was extremely methodical: All 29 of prisoners were forced to sit in an interlocking position in a trench and then buried were they fell. At the time of excavation in 2007 handcuffs, keys and various other things were found. You can see them in this post I made previously on the Sejeong Mausoleum. During this excavation enough items were found to prove that the people killed were prisoners as can be seen from the table I have included below:

This is the most inaccessible of the sites and in 2007 it was impossible to discover anything. The site is located on a forest trail in the mountain, and witness testimonies say that people were taken to this place from the second massacre site to be killed. There was nothing found by investigators in 2007, but it is said that there is indeed a small burial site by the stream where another excavation will take place in the future. At this place 5 people were found in an excavation in 2007, but Shim Gyu Sang is certain that there must be more. These people weren't prisoners as could be easily discerned at site 3 for example and what happened here seems to be most likely down to a personal or political grudge. Four of the people found here appear to be ordinary people but there is a curious aspect to one of the burials in as far as he is a high status person with leather bottomed shoes and expensive watch somewhere in his Forties buried much further away from the others. Also this person was not killed with an M1 cartridge like the other four, but a pistol instead. The main problem with excavations in this area had to do with the soil quality itself, which was full of slab stones and clay and extremely precarious to dig through. Site 6: FloodSite number six is also by the roadside in the valley close to a stream. In 2015 there was a huge storm, however, and local people say that many of the remains were washed away downstream into the city centre. There has never been an excavation at this place, but a skull was found in a Raccoon's nest in 2002 during the filming of a documentary about the Jeju Massacre. Site 7: Farm LandThis massacre site has never been excavated. It exists at the bottom of the mountain, on farm land, where the owners have been told never to disturb the ground. There will definitely be excavations here in the future, but whether or not the land owners have kept their promise has yet to be discovered. As we were standing here talking about the land owners, and the long fight against apathy here, Mr Shim turned to me and gave his riposte to those who shrug their shoulders and proclaim they “don't care”. 'This happened to innocent people', he railed as heavy trucks charged past us on the extremely narrow road, “it could just as easily be your family, or yourself'. To Mr Shim this isn't just the apathy of the landowners either. 'This war was ratified by the UN', he told me, 'it was a global event. We have to tell the world” Site 8: Pylon As Mr Shim took me to this place two hikers passed us and asked what was going on. Mr Shim told them that we were reporting on the valley, and one of them (a man in his Seventies) told us that we shouldn't call these people "ppalgenies" (the slang word for "communist" , literally meaning "red") as they were just ordinary people. That was indicative to me of a sea change in public opinion in South Korea over the last ten years or so, and it would be rare to hear such a thing in the past.

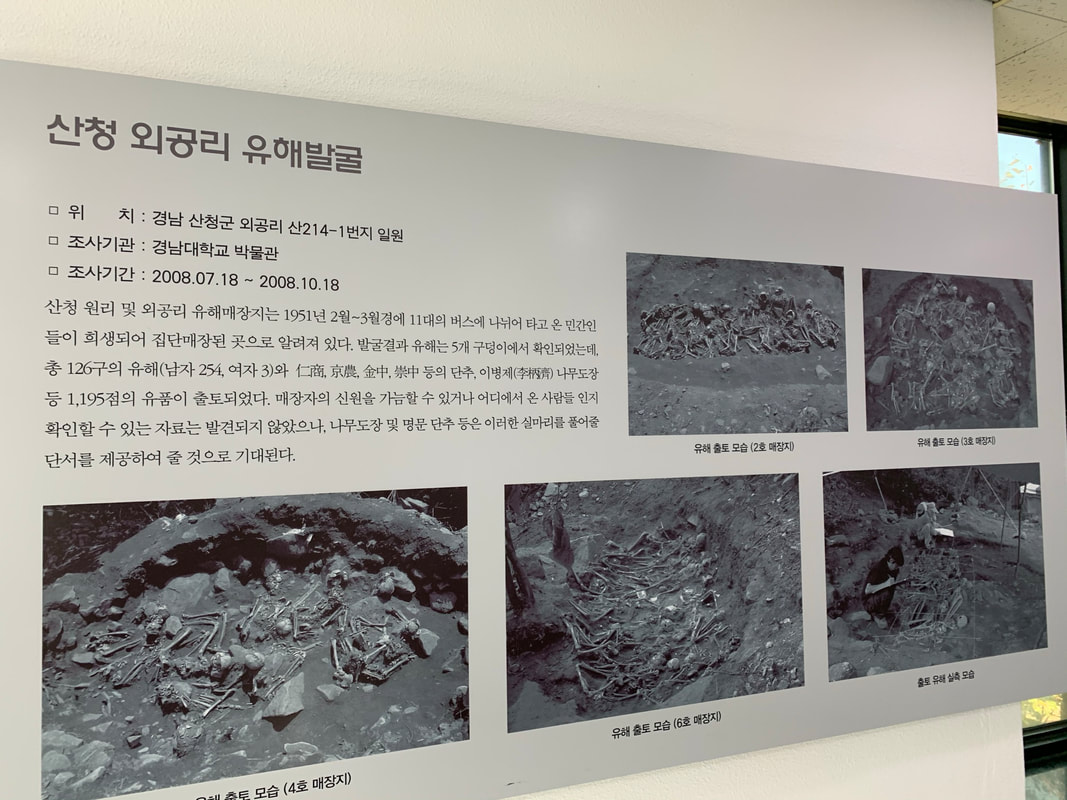

At the time the killings were witnessed by Park Song Ha from Okcheon who hid behind a tree as truckloads of prisoners were killed here when he was 15 years old. They attempted to dig here in 2007 among the trees behind an electric pylon because of another witness account, but Park Song Ha said that this was the wrong place. The bodies are buried, he tells us, underneath the actual pylon, about 10 meters to the left of where the digging commenced in 2007. When he saw them install the pylon years ago he shuddered, suddenly remembering what he had witnessed all those years ago. There is much to be written about what happened here, especially in terms of what the families suffered at this time. This place has been the subject of a poem by the local poet Jeon Sukja who's own father was killed in the valley. On the outskirts of Sejeong City this morning I accompanied Park Sunjoo to the Mausoleum where remains from the Daejeon Massacre are currently stored. This isn't just a resting place for those so cruelly murdered at this time, but also a storage facility that allows future testing of the bones. The reason for our visit today was precisely for that reason. As I arrived samples of the bones were being split into bags for a trip to Seoul where they can hopefully be identified at a later date. Once this process has been completed the families will be notified of the results, and if they want to bury the remains after all this time they will have the opportunity. When we eventually open the Peace Park in Daejeon the remains currently being excavated will also be stored on site. Hearing about all this DNA testing and how this complicated process is designed to end made me think of all of the remains that will never be identified throughout the Korean Peninsula. There will be many places like this in the North, but usually families were able to identify and bury the dead after a short period of time had passed. I would recommend people read Monica Felton's pamphlet for evidence of this. In the South, however, there was only ever an extremely small window for burials before the territory was back in control of the the American and South Korean militaries. I remember accounts of people who travelled to the site in Daejeon to recover the bodies of their loved ones at the time, only to find it impossible because of their condition. Often these people never returned to the mountain valley. It existed instead as a forbidden place at the edge of the city, a site of confluence where opposing narratives led only to a mutually agreed (or “enforced”) silence. This was a place spoken of in hushed terms by both the victors and the victims. Pain, guilt, or even ignorance, leading to a strange and terrifying omerta across the spectrum. When we were testing for DNA at the mausoleum today Professor Park showed me all of the other places that he had so far excavated for remains. One of these was the place in Gongju that originally drew my attention to this history, but there were also many others of which I had no knowledge at all. To end this post it might be worth drawing attention to one of these in particular. The ramifications of what happened at this place are instructive for many sites in South Korea, where unlike in Daejeon evidence is extremely thin on the ground. The picture above shows an excavation in a place called Oegong-ri, quite a remote area even today. The specificity of this place comes from the massacre that took place here in 1951. Nobody seems to know why these people were killed, or even where there came from. There were buttons found at the time from "Incheon Commercial School" amongst others (suggesting that many of the victims were children), but they were certainly not local people and no one seems to have come forward to claim they knew exactly who they were. All that is known is that maybe 11 buses came to this place at that time and the killing commenced soon after. Six pits were excavated in 2008.

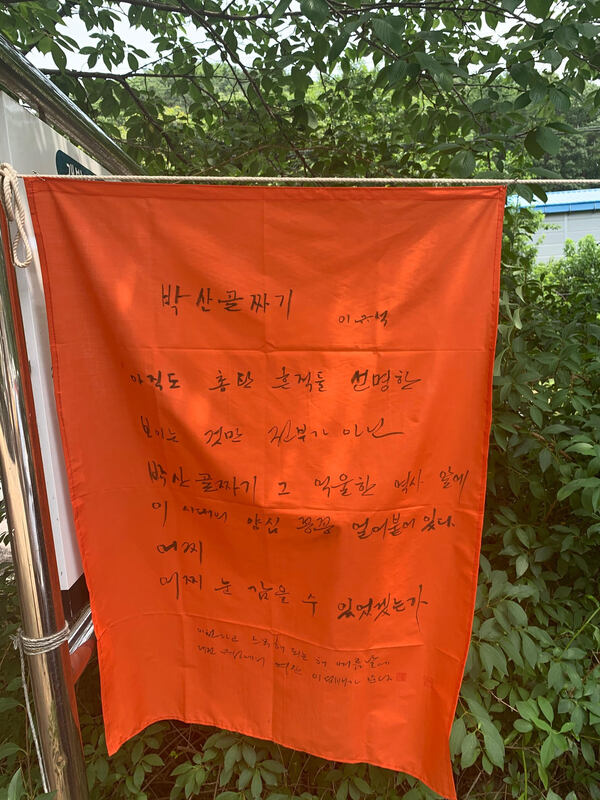

It is these kind of places that define the Korean War I think. We must focus not just on the families that received some kind of closure, but all of the people who suffered through knowing absolutely nothing about what happened to their good friends and relatives. Even the act of searching became a crime in itself, especially if the name of the person they were seeking had once been on a blacklist. The future Peace Park in Daejeon draws attention well to these unknown stories. It could bring speech and light to a place previously identified with silence and darkness. I hope in design terms that consists of a space that encourages conversation about the multiple ways in which people suffered at this time. Not just what is known as historical fact, but what could be unknown still. Which means cultivating a curiosity about the past and the future. Imagining the things that human beings have been, and could be, capable of again. One thing that has always struck me about this valley in Daejeon is the way the story always finds itself either expressed in, or involved with, poetry in both its private and public manifestations. As someone who has spent the last twenty years thinking of poetry as one way to foster an engagement -or different attention - to the world surrounding us I find this encouraging. It is something that I recognize perhaps, among so many experiences that I can only fail to come to terms with otherwise.

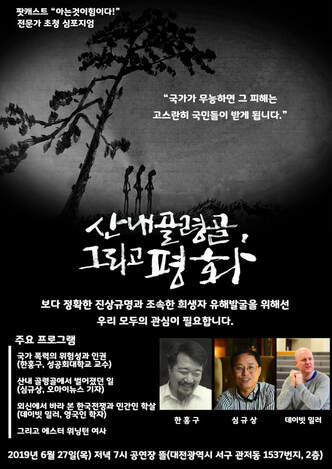

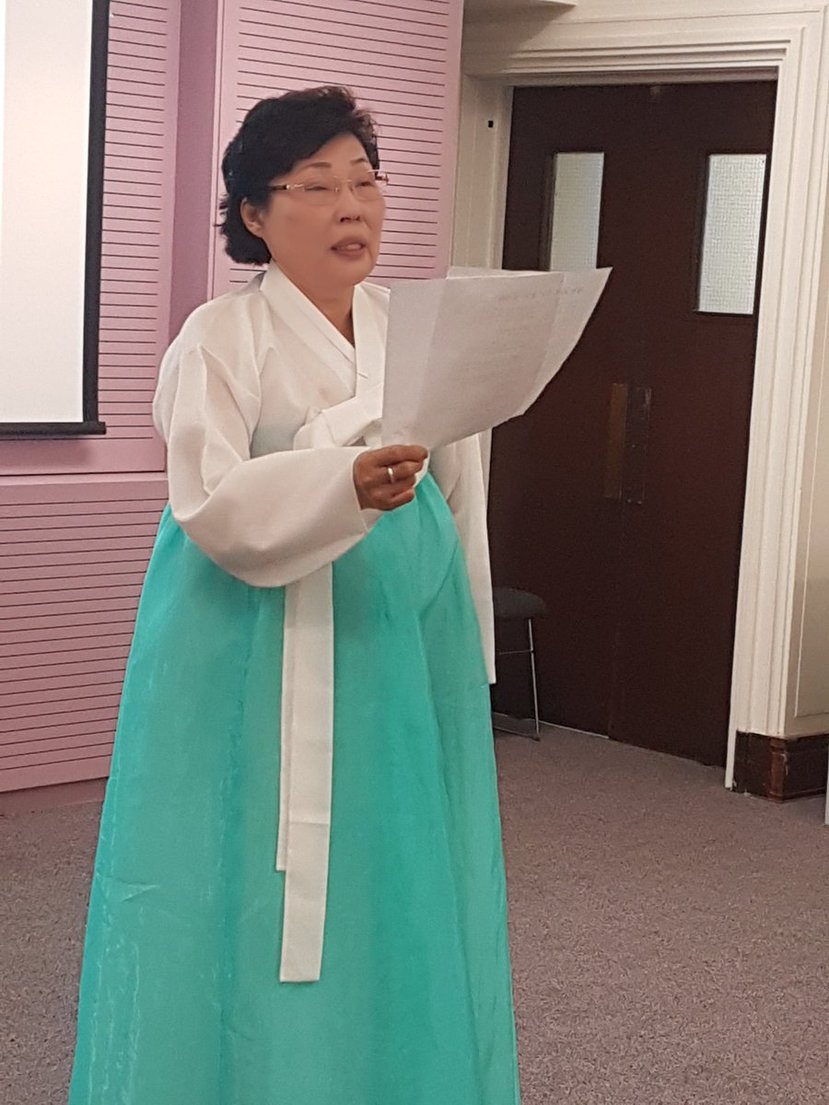

There is much to be written - and there will be shortly on this site - about the poet Jeon Sukja for whom poetry is a form of catharsis, or an extremely private and confessional way of dealing with what happened to her Father. Her story reveals one of these "untranslatable" experiences, and to see it written down and performed (always saturated with the pain of these memories) provides us with a unique and moving record of what continued to happen at this place long after fighting in the Korean War came to an end. But there are also many public expressions of poetry here initiated by the Daejeon Writers Group who I was extremely privileged to accompany to a conference on the Jeju 4.3 incident a couple of years ago. At this time of year the whole valley is usually covered in poetry banners in different colours, expressing what this history means to these writers and how it connects to other more recent historical events in South Korea. At Saturday's memorial I met the poet Park Soyoung for the second time who gave me a reading of her poem. I took my picture with her and talked about future collaborations with poets in the UK because of the Winnington connection. I hope that something meaningful can be arranged in the future.  Last years symposium on the Daejeon Massacre. Last years symposium on the Daejeon Massacre. Over the next couple of years I will be working for the local government in Daejeon in order to research the Daejeon Massacre before the building of a Peace Park here in 2024. Given the current state of the global pandemic this is proving more difficult than expected, but the goal is to have an International Conference in Daejeon at the end of this year, as well as a variety of other events that I aim to remind people of sporadically. Please get in touch if you would like to contact me about Winnington or the site in Daejeon where new information is emerging on an almost daily basis. In the first half of 2018 I was privileged to be involved in The Longest Tomb, the first documentary on a politicide in Daejeon aided and abetted by the US military in 1950. We took the film to SOAS with Mr Lee and Ms Jeon at the end of May this year. Ms Jeon read two poems, which I then explained to the audience. There was also a lively discussion at the end of the event. I truly hope I can find a copy of Ms Jeon's reading to put on this site. I will add a link to this post if one emerges. In the meantime please watch the above film, another version of which we hope to premiere in the US (Washington DC) in 2019.  Ms Jeon reads from her poem "A Wood Pigeon On The Pylon" Ms Jeon reads from her poem "A Wood Pigeon On The Pylon" There is one review of the event on Tongil news in Korea (In Korean, obviously). Click the following link: http://www.tongilnews.com/news/articleView.html?idxno=125044 There is also a similar review of the Korean premiere here: http://www.joongdo.co.kr/main/view.php?key=20180519010007868 |

Categories

All

Archives

April 2023

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed