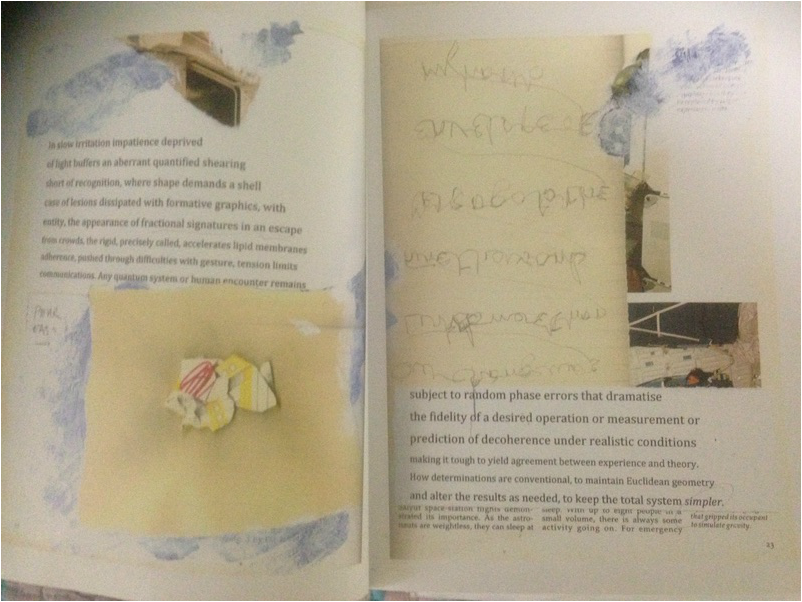

The first pages of 'human colloquium' (22-23) The first pages of 'human colloquium' (22-23) Read SPUTTOR 4 here One way to approach Fisher’s texts is through the open field that informs them. In the case of SPUTTOR this process has become far easier than it would have been for an earlier text like Place. To get a sense of SPUTTOR I downloaded what I could from the website bookzz.org, which I have found to be an excellent short cut for obtaining resources in the past. But it is also possible to approach SPUTTOR without these materials. Reference to a dictionary, for example, identifies colloquium as both ‘seminar’ and ‘hymn’. This section is identifying what is at stake in the poem, whilst conceptually justifying what will follow. SPUTTOR is human reflection. The text is a well-calibrated machine that makes that reflection possible. All of this works towards the ‘parrhesia’ promised in ‘human anticipation’. It is meant as a corrective to the duplicitous language of the state. This is, after all, the base language from within which Fisher’s text surfaces. This is discourse steeped in claims of ‘progress’ whilst dismissive of actual conditions. As self-congratulatory as it invariably is the historical origins of such rhetoric are revealing. In his “Moon Speech” at Rice University in 1962, for example, Kennedy set out the goals of the space race not just in the terms of the pre-eminence of human technology but our limitation and doubt. ‘The greater our knowledge increases’, he admitted, ‘the greater our ignorance unfolds’: Despite the striking fact that most of the scientists the world has ever known are alive and working today, despite that the fact that this nation's own scientific manpower is doubling every 12 years in a rate of growth more than three times that of our population as a whole, despite that, the vast stretches of the unknown and the unanswered and the unfinished still outstrip our collective comprehension. But in ‘[his] quest for knowledge and progress’, Kennedy asserted, ‘[man] is determined and cannot be deterred’. The confidence we have in our achievements only exists because of that deluded belief in the ‘permanence of the self’. This naked faith in the progression of humanity made way for complicity in the nefarious practices covered in ‘human anticipation’. The launching of rockets is pitched as the pinnacle of human endeavours. Everything that has happened, and will happen, generates from this single point. Kennedy’s words resonate strongly in terms of a text like SPUTTOR because of the ‘double speech’ implicit in them. ‘We have vowed that we shall not see space filled with weapons of mass destruction’, he insisted, ‘but with instruments of knowledge and understanding’. Warnings against the ‘hostile misuse of space’ seem hollow in the light of the Strategic Defence Initiative that ran parallel with the Challenger mission. The ‘ignorance’ of humanity so readily admitted by Kennedy is surely no more apparent than in the hubris of the governing classes. The space race no longer reveals a world in which the west is “number one”, but the grounds of an almost unutterable contradiction. Fisher’s choice of the Challenger mission is interesting, because there is no event that displays the hubris of the west in more blinding detail. In Robert Trivers’ text The Folly of Fools: The Logic of Deceit and Self Deception in Human Life (2014), he positions this disaster above all others as the perfect example of an ‘internal self deception’ structuring thinking in the West. ‘Since it was necessary to sell this project to congress and the American people’, writes Trivers, ‘[m]eans and concepts were chosen for their ability to generate cash flow, and the apparatus was then designed top down’. According to Trivers the O-ring – that is, the component that is said to have brought down Challenger – had already been identified as faulty by the engineers in charge[1]. NASA’s journey into space was unnecessary on this occasion, with a focus on ‘stunts’ of ‘marginal educational value’. This was a monumental waste of money and resources, manufactured to serve political ends. ‘Thus was NASA hoisted on its own petard’, writes Trivers, ‘the space program shares with Gothic cathedrals the fact that each is designed to defy gravity for no useful purpose except to aggrandize humans’. ‘Stunts’ such as these are all that can be expected from a world suffering under layers of duplicity. Something like poetry is particularly sensitive to this atmosphere. If truth exists then it can only be in the sense that it does for Gerard Richter, someone quoted by the artist in his essay “Complexity manifold 2: Hypertext”. ‘For Richter, truth is fragmentary, its enemy – ideology – is ultimately murderous, and history is irremediable’, Fisher explains, ‘[g]ood does not necessarily rise from the ashes: it is more likely blown by the wind leaving behind a damaged consciousness’. To Fisher our ‘self deception’, and ‘error’, are visibly manifest in grandiose projects such as these. Picked apart they reveal a tremulous, and disorientated, human condition. History is claimed, once again, as farce with the later Colombia disaster standing as evidence. Away from space missions the same logic throws new light on how we perceive a phenomenon such as climate change. Constant ‘denials’ against a weight of scientific evidence simply ‘perpetuates the state machine’. In a poem such as SPUTTOR language must be seen as heavily invested in this deceit. The fragments of text and image in Fisher’s collage are taken from a world caught up in what Trivers would call a ‘reality evasion’. ‘[I]n service of the larger institutional deceit and self-deception, the safety unit was thoroughly corrupted to serve propaganda ends’, writes Trivers on Challenger, ‘that is, to create the appearance of safety where none existed’. In ‘human colloquium’ an effective counter narrative is given the opportunity to emerge. Parrhesia – seen in human anticipation as ‘indispensible for the city and for individuals’ – will come about only through effective engagement with the materials. Parrhesia, then, is something opposed to the duplicitous rhetoric of the state, or a form of speaking beyond the ‘private pretense, public affirmation, or purposeful suggestion of what’, Fisher claimed during Confidence In Lack (2007), ‘is knowably false’ (12). These are the kind of observations Fisher takes from Bernard William’s Truth or Truthfulness (2004). The world we inhabit – given the absence of ‘state conscience’ – is revealed by Fisher as one of ‘self deception’ or ‘active deceit’ (12). This constant back slapping in the western world is actually based on an extreme cognitive dissonance. Parrhesia in Fisher’s text must go further than merely parroting these untruths, it has to be opposite of that ‘spoonfeeding’ mentioned earlier. Indeed, the passage from Williams below articulates an attitude to reading equally applicable to SPUTTOR itself: As Roland Barthes said, those who do not re-read condemn themselves to reading the same story everywhere: 'they recognize what they already think and know'. To try to fall back on positivism and to avoid contestable interpretation, which may indeed run the risk of being ideologically corrupted: that is itself an offence against truthfulness. As Gabriel Josipovici has well said "Trust will only come by unmasking suspicion, not by closing our eyes to it". While truthfulness has to be grounded in, and reveled in, one's dealings with everyday truths. That itself is a truth, and academic authority will not survive if it does not acknowledge it (12). For Fisher, perhaps, this is where parrhesia becomes most vital in his text. What is presented in the work certainly isn’t a ‘speech’ by the poet but an attempt to engage with the complexities of a human situation that has otherwise been subsumed in the ‘active deceit’ of ideological factors impinging on aesthetic practice. One way of rupturing this narrative is with the ‘planned imperfection’ of his technique, which not only forces a ‘re-reading’ but makes sure that it is always contestable. Such a text must ‘stride out’ as Fisher puts it in his soon to be released text from the University of Alabama Press, unperturbed ‘into the performance of its presentation’. The prime instrument for ‘contestability’ in SPUTTOR is damage. Damage creates the opportunity for transformations by interference with reader perception. In lieu of a finished product, both reader and writer must settle for ‘confidence in lack’. The work springs up between the gaps in what we know. Rather than relying on habitual patterns of perception, there is an attempt to disrupt these thought processes through ‘planned breakage’ (Confidence in Lack 13). There are numerous aesthetic strategies at play in SPUTTOR, but all of them are working towards such an end[2]. On the first page of this section – together with a screwed up piece of paper bearing the traces of red first seen in human anticipation – the writing explains the ‘slow irritation’ and ‘impatience’ that can be expected when encountering a text such as this: In slow irritation impatience deprived of light buffers an aberrant quantified shearing short of recognition, where shape demands a shell case of lesions disssipated with formative graphics, with entity, the appearance of fractional signatures in an escape from crowds, the rigid, precisely called, accelerates lipid membranes adherence, pushed through difficulties with gesture, tension limits communications. Any quantum system or human encounter remains. Here ‘light buffers’ (which this reader can only translate loosely as ‘optical fibers’ and therefore a means of communication) are subject to an ‘aberrant quantified shearing’. These lines portray perceptual data as deviating from logical patterns in SPUTTOR by way of Fisher’s post-collage method. This ‘shearing’ creates the damage that disrupts traditional modes of communication. The collage Fisher creates in the text is ‘short of recognition’, it is ‘shapeless’ and as such the reader ‘demands a shell’ of coherence to aid interpretation. These are ‘fractional signatures’, as Fisher calls them almost in direct reference to his authorial mark earlier, in ‘an escape from crowds’. They are the ‘anchors’ that have always been important to Fisher, the strategic points of recognition by which any effective reading has to begin. ‘Crowds’ could be taken quite literally, here, in the sense of that ‘over stimulation’ that caused anxiety for Wordsworth in his preface to Lyrical Ballads, or the fear of a ‘paralyzed imagination’ that Walter Benjamin wrote of in “On Some Motifs in Baudelaire”. But ‘crowds’ also seems to reference Fisher’s own term ‘crowd out’. This would be the ‘crowding out’ of other possibilities in the work, or the dogmatic reliance on a single ‘anchor’ in order to assist reading[3]. What is important is that ‘[a]ny quantum system or human encounter’, as Fisher has it, ‘remains’. The poem is both the bared processes of some ‘quantum system’ – see Steven Hitchen’s revealing exchange with Fisher ‘Kinghorn Quantum’ for more specific evidence of this – and the site of genuine human participation as it attempts to create meaning.  Pgs 22 - 23 of Andrew Wilson's Space Shuttle Story Pgs 22 - 23 of Andrew Wilson's Space Shuttle Story This approach is continued across the page, where readings appear independently of what immediately presents itself as ‘poetry’. The poem, this time, is pasted over a scene of domestic life on board the shuttle from Wilson’s text. This is a scene that seems to benignly show ‘activity going on’ if we are to believe the fragments that remain. Indeed, in the actual text at this stage Astronauts’ Rhea Seddon and the (almost eponymous) Anna Fisher are seen preparing ‘meal trays’ and ‘testing the sleeping arrangements’ on board the shuttle in November 1984. The descriptions, here, are of ‘domesticity’ and ‘comfort’ as the astronaut’s try their best to simulate life on earth under zero gravity conditions. Because of Fisher’s damage, however, the isolated text reads: ‘activity going on. For emergency’ (23). This is the same kind of spontaneous transformation that emerged in the pagination of ‘human anticipation’, where ‘products and services’ became juxtaposed to Newton’s law of action and reaction. Unable to get a sense of exactly what is being described in Wilson’s original, the damage presents the astronauts as engaged in domestic activities whilst oblivious to the emerging disaster. This scene of domestic activity is transformed by Fisher to create another situation entirely. In SPUTTOR interpretation not only relies on, but also ruptures, Wilson’s original message to send the viewer in unexpected directions. These are intentional aesthetic strategies employed by Fisher, and invoke a mixture of all of the methods for ‘breakage’ footnoted previously. ‘Fractional signatures’ are alive in the background of the work, which makes any progress through the text subject to a constant ‘re-reading’. SPUTTOR isn’t an expository text like Wilson’s, but a different entity entirely. Fisher plays with the conventions of his own work, whilst at the same time disrupting the continuity of Wilson’s own narrative. The original has been ‘replaced by larger/ experimental units’ as a similarly recovered fragment from Wilson’s text puts it and the transformations can sometimes be equally ‘cutting’. Some of the astronauts pictured in Space Shuttle Story at this juncture (such as Mc Nair on page 22) actually died in the Challenger disaster itself. Although this is, rightly, left alone in SPUTTOR, there is still a sense of foreboding that is generated by this easily inferred knowledge. SPUTTOR allows the participant the opportunity to perceive our historical progression from an entirely different vantage point, by physically occupying the space of a text struggling with its own set of limitations and doubts. ‘We saw the ruins of this hapless city from the height of the tower …’, as Mary Shelley put it in The Last Man, ‘and turned with sickening hearts to the sea… which needs no monument, discloses no ruin’ (574 – 575). Since ‘human anticipation’ there has been a visual tension in SPUTTOR as the text switches back and forth between this image of damage and more traditionally conceived attempts at versification. On page 14 for example – as part of ‘human conditions’ – that screwed up piece of paper has already been presented in a section from Wilson’s text that describes the ‘shuttle tak[ing] shape’. But as the text progresses through ‘human health’ (18 – 22) and onwards there are examples of attempts at what appear to be hand written notes almost as if the artist is struggling with articulating the subject matter of SPUTTOR within the bounds of a more traditional form of composition. The main example of this on page 20 is barely legible, but the visible marks are still important in the play off between text and image that has defined SPUTTOR so far. By ‘human colloquium’ the text has finally become unreadable. This is significant in itself, in as far as what remains is like an attempt at ‘automatic writing’. This is something that Fisher commented on in his 1978 talk at Alembic, and his words seem increasingly important in light of page 23: The impossibility of used structures, of using structures. The impossibility of not doing so. One of the – I’m not quite sure what category to put it in – one of the poetries that I have distrust of is those poetries that speak of automism, automatic writing. If the person who is the automatic writer is telling me that he’s getting something which does not repeat. It is not possible to not use your structure. Your own memory bank, if you like, body make up, your own nerval feeling, emotional complex. It is not possible to write without use of that, unconsciously or otherwise. What I would like to lead to then is to say, as that is the case, shouldn’t we be making ourselves more conscious of what that structure is’ (44). The visual play off between an ‘automated’ view of composition such as this, and Fisher’s own attempts at damage in SPUTTOR, physically enact the kind of tensions in all his works. On page 23 the automatic writing is seen to reach down and touch another passage of text by Fisher that seems to be juggling with the same tensions. The worry in SPUTTOR seems to be ensuring the ‘fidelity of desired operations’ – that is accuracy, or some kind of effective ‘measurement’ – amongst all this damage or ‘random phase errors’. It is as if something is being ventured deliberately calibrated to yield inventive perception in a way that hasn’t been tested by the artist previously. Pages 22 and 23 – in image alone – provide a juxtaposition that will be central to the procedure of SPUTTOR as it progresses. The problem at this stage seems to be ‘yield[ing] agreement between experience and theory’, or creating a poem that doesn’t ossify within the central conceit of the artist. Fisher’s model for this over the next few pages is Walter Benjamin, the original master of literary collage. I will add one more post to this series on SPUTTOR shortly, specifically on this relationship to Benjamin and his ‘dialectical image’. [1] ‘All twelve [rocket engineers] had voted against flight that morning’, writes Trivers, ‘and one was vomiting in his bathroom in fear shortly before take off’. This is an example of institutional ‘self deception’ on a massive scale. Those who claim to have our best interests at heart, such as the ‘safety unit’ at NASA, are actually motivated by a ‘self deceived approach to safety’ that puts everyone at risk. As Trivers makes explicitly clear: When asked to guess the chance of a disaster occurring, they estimated one in seventy. They were then asked to provide a new estimate and they answered one in ninety. Upper management then reclassified this arbitrarily as one in two hundred, and after a couple of additional flights, as one in ten thousand, using each new flight to lower the overall chance of disaster into an acceptable range. As Feyman noted, this is like playing Russian Roulette and feeling safer after each pull of the trigger fails to kill you. In any case, the number produced by this logic was utterly fanciful: you could fly one of these contraptions every day for thirty years and expect only one failure. The original estimate turned out to be almost exactly on target. By the time of the Columbia disaster, there had been 126 flights with two disasters for a rate of one in sixty-three. Note that if we tolerated this level of error in our commercial flights, three hundred planes would fall out of the sky every day across the United States alone. One wonders whether astronauts would have been so eager for the ride if they actually understood their real odds. [2] This passage from Confidence in Lack seems to give a sense of just some of the strategies in Fisher’s repertoire around the time of publication: At the level of the words in the text, for instance, transformations may be used that deliver word links, patterns of connectedness, through the use of sound (rhyming) and, comparable meaning(rhetoric), discussion or disruption of meaning (poetics), and damaged pasting (found in most genres including poetry, painting and comedy). The factured product has thus undergone a series of breakages and factures. Sometimes this series involves transformation, planned breakage and incidental repair, sometimes the work uses collagic disruption of spacetime, and often the pasting together of different sections simulates continuity (13) [3] Working in the medium of collage – or ‘post collage’ which he terms a form of ‘realism’ – crowd out is a term that Fisher uses to describe a situation where ‘one reality’ obscures another. The origin of the term is actually economics (it is possible to find reference to it in the works of Michael Sandel for instance). Other than in my description above, Fisher describes it himself as a facet of viewing an art work at which point ‘One sensation, or one perception, crowds out another for a moment, or for a period’ (115). |

Categories

All

Archives

April 2023

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed