|

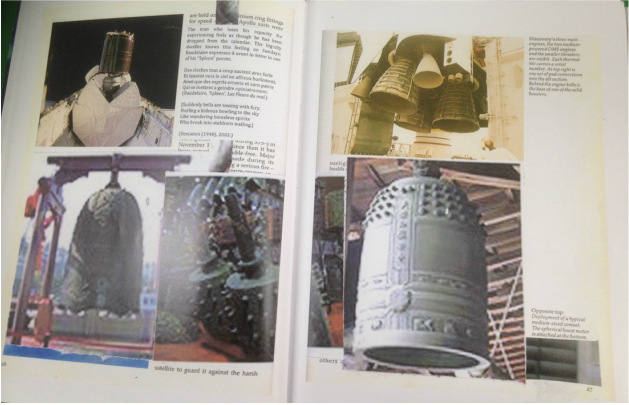

Read SPUTTOR 5 here In my post on ‘human anticipation’ I noted that history in SPUTTOR is associated early on with blue and a sense of the ‘intangible’. This is against the irretrievable history in Richter earlier. There is hope to be squeezed out of contemporary conditions, but this hope is not something that is easily located. In “Complexity Manifold 2” Fisher writes of ‘the aesthetic swerve’ as fundamental in this context. This is a phrase taken from Joan Retallack’s The Poethical Wager (2003) who in turn borrowed it from Epicurus[1]. For Retallack aesthetic swerves are necessary devices to jolt readers out of complacency. During “Complexity Manifold 2” Fisher quotes Retallack defining a ‘poethics’ as ‘what we make of events as we use language in the present’, or ‘how we continuously create an ethos of the way in which events are understood’. ‘Swerves’ are necessary because they ‘dislodge us from reactionary allegiances and nostalgias’. History is only ‘retrievable’ if formal concessions are made towards recognizing this situation. Otherwise poetry remains just another form of ‘self deceit’, something resistant to interpreting the conditions that surround it. Indeed, there seems little point in writing if the goal is to simply reassert a reality that has a chokehold on the truth. But the medium of poetry seems especially resistant to attempts at ‘innovation’ in the popular mind. It must be a region of comforting traits where language conforms to preconceived notions of what poetry is. Retallack contrasts this view with commonly accepted perspectives on the role of science in public life. ‘There are numerous versions of these qualms about the efficacy of experimental thought’, she writes, ‘except in the sciences, where it is seen as the nature of the enterprise’ (5). These arguments are well-rehearsed. ‘Give up the poem’, as William Carlos Williams famously put it in Paterson, ‘give up the shilly-shally of art’. The parallels to Fisher’s own work are immediately striking. ‘He had become the subject of the manifestation of truth’, writes Fisher of his own predicament, ‘when and only when he disappeared or he destroyed himself as a real body or a real existence’. But this isn’t the immediately recognizable ‘death of the author’. Instead of ‘disappearing’ completely any tyrannical hand is rendered diffuse over a greater area. As Retallack insists, ‘agency’ must be seen in ‘the context of sustained projects’, where ‘swerves occur, but which one guides with as much awareness as possible’ (3). These ‘alternative kinds of sense’ result in an entirely different order of perception. ‘Control isn’t bad’, as Fisher once explained in reference to the scientist Arthur Eddington, ‘if it’s your own control over your own self’ (51). With this knowledge the blue in SPUTTOR stands for the unknowable qualities of meaning beyond human perception. The mark of the author, in opposition, will always be red. Any trace of personality is embargoed from the start. The author is not erased, but ‘damaged’ from the outset. On pages 26 to 27 the guide is Walter Benjamin, who famously examined the possibility of interrupting monolithic historical narratives through what he termed aesthetic ‘shocks’. ‘The present’, as Benjamin had it, ‘is an enormous abridgement’. ‘The history of civilized mankind’, as he paraphrased the words of a “modern biologist” during his “Theses on the Philosophy of History”, ‘would fill one fifth of the last second of the last hour’ (255). As already made clear, such a ‘revisioning’ is a major focus of SPUTTOR itself. As Fisher writes of the current epoch, we are at the very end point at which a plan for the resuscitation of human history will ever emerge: This period of stability, the Holocene (entirely recent stability) is almost certainly now under threat. A new era has arisen, the Anthropocene (human recent, coined by Paul Crutzen) in which human actions have become the main driver of global environmental change since the industrial revolution in Europe. Johan Rockström and 28 colleagues (including Crutzen) from the Stockholm resilience centre, propose a framework based on “planatery boundaries”. These boundaries define the safe operating space for humanity with respect to the earth system, and are associated with the planet’s biophysical subsystems or processes. By drawing our attention to such a time line Fisher aims to displace the anthropocentricity of ‘universal history’. Leaving the planet in SPUTTOR is an attempt to gain a new perspective on this distinctly human dilemma. The shrill, and conceited, trajectory of human ‘progress’ has to realise its limitations if the human race is to survive. The melioristic conception of time that makes manufactured ecological ‘boundaries’ necessary is responsible for the ‘self deceit’ that currently burdens human thinking. In the light of these extreme conditions, and in the same manner that Benjamin had attempted, it is impossible to conceive of history in the first place without acknowledging the duplicitous state narratives informing it. ‘The concept of the historical progress of mankind cannot be sundered from the concept of its progression through a homogeneous, empty time’, as Benjamin put it long ago, ‘[a] critique of the concept of such progression must be the basis of any criticism of the concept of progress itself’ (252). At this stage in SPUTTOR the main textual element switches from poetry to the juxtaposition of fragments much like in Benjamin’s own work. On page 26 Fisher includes quotations from Benjamin during “On Some Motifs in Baudelaire”. Here, the writer comments on one of Baudelaire’s Spleen poems which describes ‘bells’ ‘tossing with fury’ amongst ‘homeless spirits’ ‘break[ing] into stubborn wailing’. What Benjamin was interested in identifying in Baudelaire was the alienation of a human race that has ‘los[t] its capacity for experiencing’. This is experience of time in the city as it has been wrenched from reality. ‘Although chronological reckoning subordinates duration to regularity’, wrote Benjamin in the original sentences preceding Fisher’s isolated text, ‘it cannot prevent heterogeneous, conspicuous fragments from remaining within it’ (336). No matter how hard the dominant historical narrative imposes itself on the idea of human progress, glimpses of alternatives emerge. The bells in Baudelaire’s poem – ‘tossing’ with ‘fury’ – are juxtaposed in Fisher’s ‘damaged’ text with the ‘engine bells’ on Challenger. On pages 26 and 27 it is possible to see two aspects of the space shuttle design mirroring a bell shape common in fractal geometry. The bells in Baudelaire’s poem clearly hold some as yet unknown affinity with the ‘engine bells’ on Wilson’s photo of the shuttle. This is a relationship that sees the trajectory of bell design as something interpreted over and over again outside of human history with different modifications each time. Rather than viewing time as progressing in a teleological fashion towards an inevitable ‘human improvement’, rocketry is seen in terms of an expanding series of which it is an inevitable part. The idea of the shuttle is simply a modified version of a shape that occurs somewhere in nature. Human appropriation of this design refers to no innate genius in the species. According to Fisher’s ‘Image Resources’ section the bells in SPUTTOR include the JINGYUN bell, and the Xi’an bells from ‘the warring states in the Hubei provincial museum’, but also the ‘Ryoan Ji’ bell contained in the ‘Temple of the Dragon of Peace’ in Kyoto (127). Unlike in Wilson’s text, these fractal shapes have been put to numerous uses throughout human history rather than being appropriated within the terms of shuttle design. Bells such as these escape tribal boundaries or affiliations synonymous with state power. Used in war, and times of peace, such bells also exist in cultures with cyclical understandings of time the very antithesis of the linear model informing the Challenger mission. On pages 26 and 27 of SPUTTOR Wilson’s original text takes on another transformation. Rocketry is glimpsed from within the prism of an ever-expanding complexity. Technology is separated from its violent origins in the west and revealed as part and parcel of a much wider condition. Kyoto – the location of the ‘peace bell’ – opens up a further series of connotations when considered within the context of the nuclear bombs that where dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki in the closing stages of the Second World War[2]. As the ultimate manifestation of the indefatigable belief in rocketry, the erasure of entire cities points to an imbalance in how technology is perceived at this ‘human colloquium’. Instead of ‘a bumper year for space achievements’, its cynical use has become simply another way of ‘perpetuat[ing] the state machine’. On pages 28 -29 of SPUTTOR this reading of history is confirmed via another section from Benjamin’s essay. The first day in November, the Day of the Dead, is seen as absent from western narratives of progress like that enshrined in the Challenger mission. ‘The duree from which death has been eliminated has the affinity of a bad ornament’, writes Benjamin of Baudelaire’s poem, ‘[t]radition is excluded from it’ (29). ‘The melancholy man sees the earth revert to a state of nature’, the theorist continues, ‘[n]o breath of prehistory surrounds it – no aura’ (29). But Fisher juxtaposes across from Benjamin’s new quotation a section from Adorno that criticizes the theorist’s method. There is an element of self-reflexivity here aiming to comment on the formal progression of Fisher’s own text. The chosen quotation is taken from a well known exchange between Adorno and Benjamin that has come to define all future work aiming to proceed by the juxtaposition of text and image. In the quotation from SPUTTOR Adorno criticizes some lines from the Arcades Project when Benjamin refers to the dialectical image as ‘utopia’ or ‘dream’[3]. As George L. Dillon has made clear in his essay “Montage/ Critique: Another Way of Writing Social History” (2004), which draws heavily on John Berger and others who have attempted to use Benjamin’s procedure in their own work: [Benjamin’s example] points to certain practical issues about writing by juxtaposition and constellation of fragments (montage). The fragment, or more broadly the constellation, must speak for itself: this means not only that a single definitive authorial perspective must be removed, but also that the fragment/ constellation must remain open to further seeing. Adorno feared that by this evacuation of subjectivity (of the interpreter), Benjamin had inadvertently presented a view of the world as mere uninterpreted fact – of material, observable things, and unique, unanalyzable events – which the reader would have no reason to connect to theory at all.” (3) Benjamin’s dialectical image, in this sense, could represent a stopping of the processes that are so important to Fisher. Adorno’s critique continues to have major ramifications when considering text and image in alignment in this manner. The author cannot simply ‘vanish’ from the text, and leave interpretation open to a small circle of ‘true believers’ who are able to ‘get’ the references put forward. ‘Benjamin could not resolve the contrary objectives of author-evacuated montage presentation’, writes Dillon, ‘and the need to provide theoretical, ethical guidance for the reader’ (3). If Fisher is ‘guiding… with as much awareness as possible’, to use Retallack’s words earlier, ‘then it seems obvious that SPUTTOR is attempting something contrary to the usual ‘author evacuated montage’. Perhaps this is why page 28 shows Fisher’s automatic writing with that ‘screwed up’ piece of paper resting on top of it. To avoid Benjamin’s own predicament, the ‘damage’ in SPUTTOR is an element that attempts to rectify these fundamental difficulties in composition. SPUTTOR is not dialectics ‘at a standstill’, as Benjamin put it, but a genuine attempt to interfere with any idea of ‘utopia’ or ‘dream’ that might come from the constellation itself. The authorial red in the text has been focussed from the outset upon disrupting precisely such claims. Fisher’s text, then, is not ‘parrhesia’ in the sense of rhetoric. On page 31, for example, it is clear that this ‘truth telling’ is itself subject to a kind of ‘double damage’. ‘PEAR EASIER’, as Fisher mockingly reorders this vital word, will not escape scrutiny. ‘Truth telling’ will emerge independently in SPUTTOR, there can never be the kind of ‘uninterpreted fact’ of which Adorno accused Benjamin. The ‘parrhesiast’, as Foucault explained in The Courage of Truth, ‘is not a professional’ (14). By the same token it would be wrong to situate SPUTTOR as an attempt at rhetoric plain and simple. To use Foucault’s description of the term, parrhesia is more like a ‘stance’ or ‘mode of action’. The parrhesia in SPUTTOR comes not from what kinds of things are said, as much as the way they become articulated in the first place. On the bottom left of page 29, for example, Fisher reappropriates the words of the Invisible Committee, to give a sense of precisely why such strategies are necessary. In Fisher’s ‘found poem’ different sections of the Committee’s text are presented in a collage that defines our contemporary SPUTTORings. ‘Certain words’, a section of Fisher’s Invisible Committee collage reads, are like battlegrounds, their meaning, revolutionary or reactionary, is a victory to be torn from the jaws of struggle’ (28). The word the Committee is referring to at this point – “communism” – is precisely the kind of concept it is almost impossible to utter in the present. At the time of writing, when a Conservative government has once again taken the reins of power in Britain, a word such as this will be further suffocated beneath a self congratulatory discourse that sees it as something abandoned within the liner progression of time. But writing like SPUTTOR is necessary because without the method of the parrahesiast there can be no attempt to picture language outside of the universal history within which it has become embedded. In Fisher’s found poem The Committee writes of a ‘drone’ that was discovered in the suburbs of Paris ‘unarmed’, which ‘gives a clear indication of the road we’re headed down’ (28). Rocketry isn’t simply a benign historical ‘spectacle’ at the culmination of human progress, in this sense, but something that has spread out to encompass all aspects of everyday life. The drones may not be armed in this time of relative ‘peace’, but you can be certain that they will be once the interests of the state are threatened. The beauty of Fisher’s poem comes in how urgently it speaks from within the gaps of the sanctioned, and sanctimonious, discourse of the present, without abandoning himself to the ‘stand still’ of the ‘dream’ that haunted Benjamin. To do otherwise would be to replace one form of ‘self deceit’ with another, an authorial imposition that does nothing to heal the fissures that blight the anthropocene itself. [1] 'Epicurus posited the swerve (aka clinamen) to explain how change could occur in what early atomists had argued was a deterministic universe that he himself saw as composed of elemental bodies moving in unalterable paths', writes Retallack, 'Epicurus attributed the redistribution of matter that creates noticeable differences to the sudden zig zag of rogue actions. Swerves made everything happen yet could not be predicted or explained' (2) [2] The location of the ‘peace bell’ in Kyoto is interesting to consider. The original target for the first A-bomb, Kyoto was taken off the list of targets after the obliteration of Dresden had caused such controversy. The bombing of Nagasaki and Hiroshima, then, could be seen as an early attempt at twisting the narrative of rocket technology within the terms of state propaganda. This is without even considering the mind boggling rumours that the US Secretary of War Henry S Stimson was reticent about targeting Kyoto as he had been a regular traveler to this area of Japan before the war even enjoying his honeymoon there [3] ‘Ambiguity is the figurative appearance of the dialectic, the law of the dialectical at a stand still’, to quote Benjamin exactly, ‘this standstill is utopia, and the dialectical image is therefore a dream image’ (Arcades 171). |

Categories

All

Archives

April 2023

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed