|

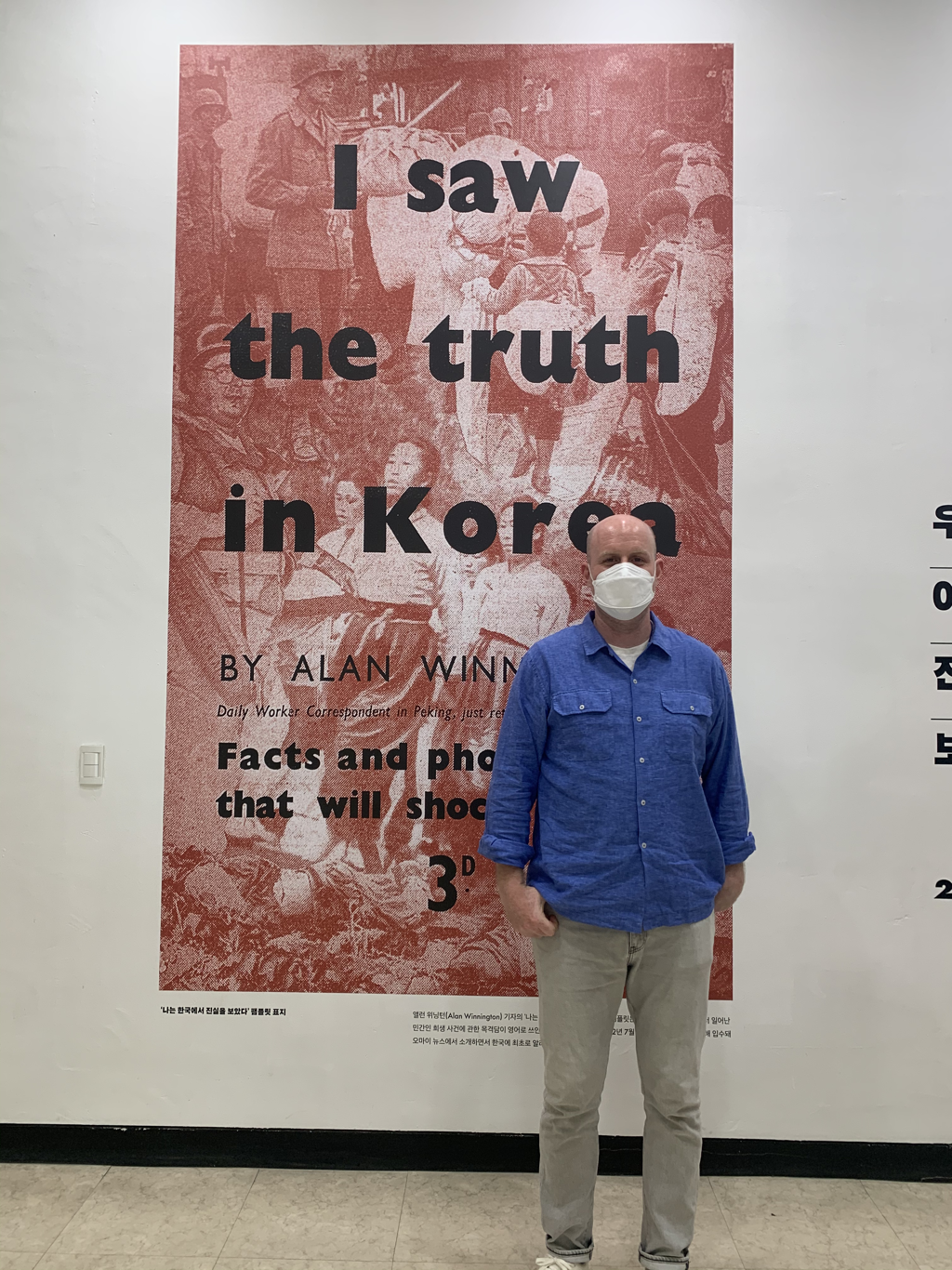

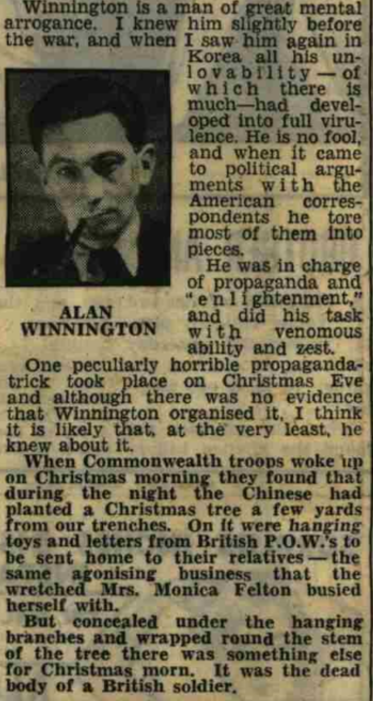

“Facts cannot be hidden forever... all we have to do is our share of getting the truth known” The above quote is taken from a letter from Winnington to the POW Andrew Condron in 1952. It still stands. So much is left over from the Korean War that is little understood or appreciated. This is why I wanted to be involved so much in this exhibition of Winnington’s photographs that opened today in Daejeon. It wouldn’t have been possible without the local council, and the amazing knowledge of local activists Shim Gyu Sang and Im Jaegeun. I could only contribute to the Winnington aspects of everything there. This was “my share”. I will continue to contribute for the same reasons wherever possible. Both because it is so necessary for a lasting peace in Korea. But also because Winnington himself is so misunderstood. Everyday there is new information that astounds me - and every day I am shocked by the consequences of what he witnessed. This excerpt from a “Cassandra” article in the Daily Mirror in 1955 is indicative when we consider the lies and misinformation that was spread around at the time. Not an attempt to “get the truth known” but to obscure it further. This is one of the main reasons we can only “s[ee] the truth” today. The exhibition will be open for ten days in Daejeon this week. At the 전통나래관 behind Daejeon Station (if anyone is reading this in Korea) One thing that has always struck me about this valley in Daejeon is the way the story always finds itself either expressed in, or involved with, poetry in both its private and public manifestations. As someone who has spent the last twenty years thinking of poetry as one way to foster an engagement -or different attention - to the world surrounding us I find this encouraging. It is something that I recognize perhaps, among so many experiences that I can only fail to come to terms with otherwise.

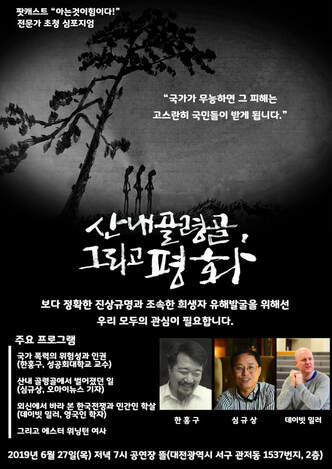

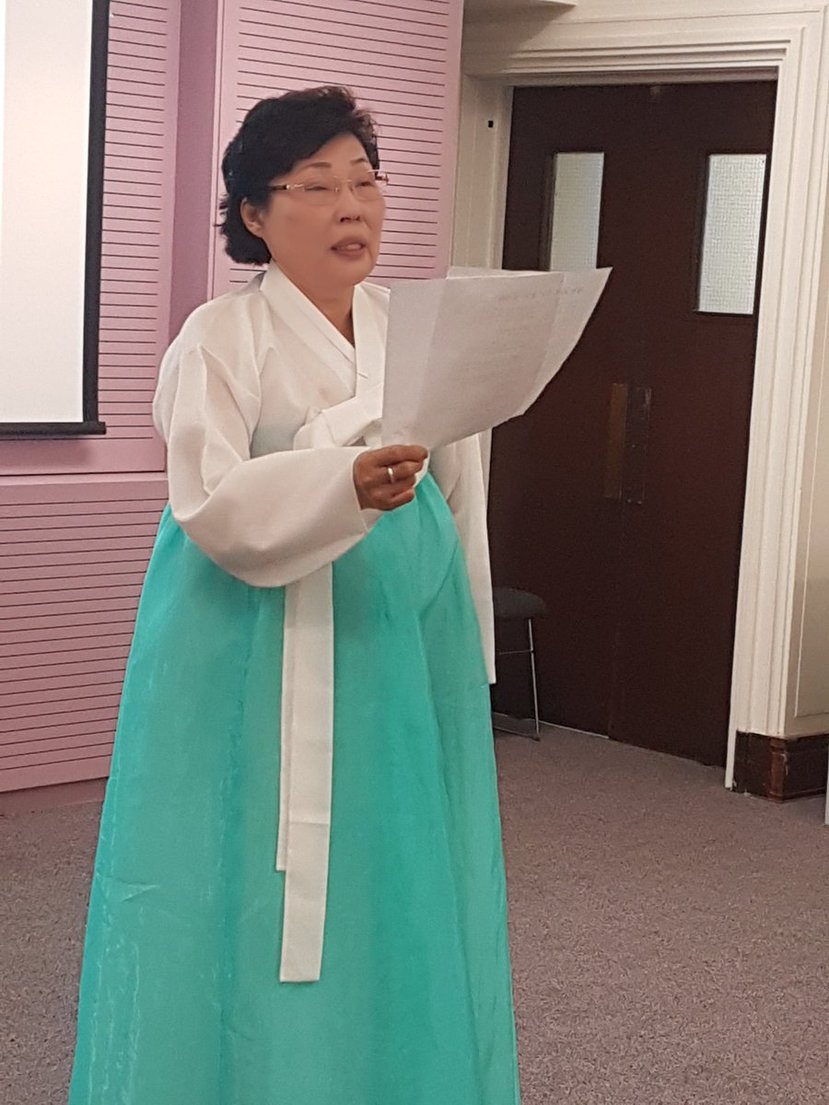

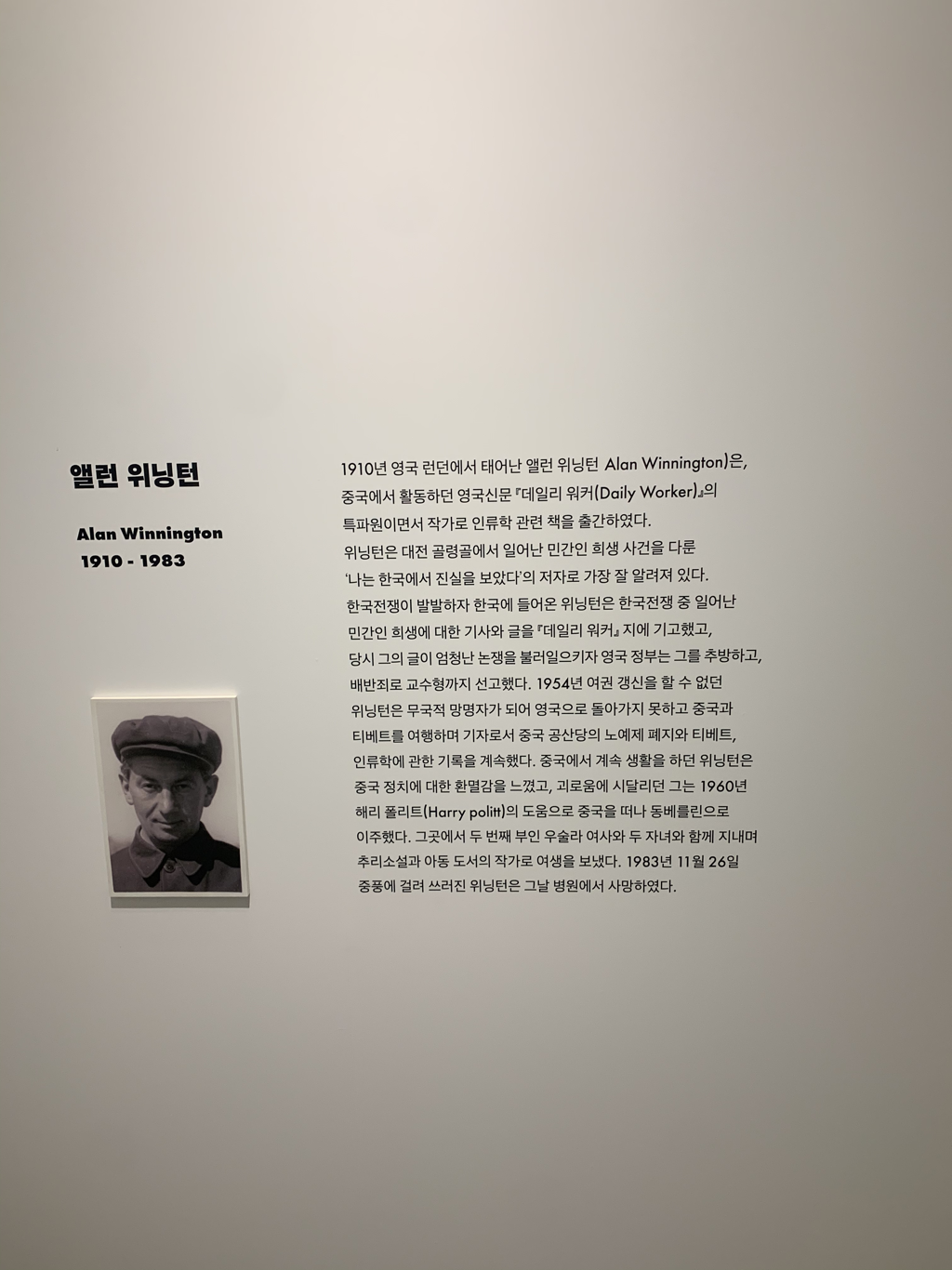

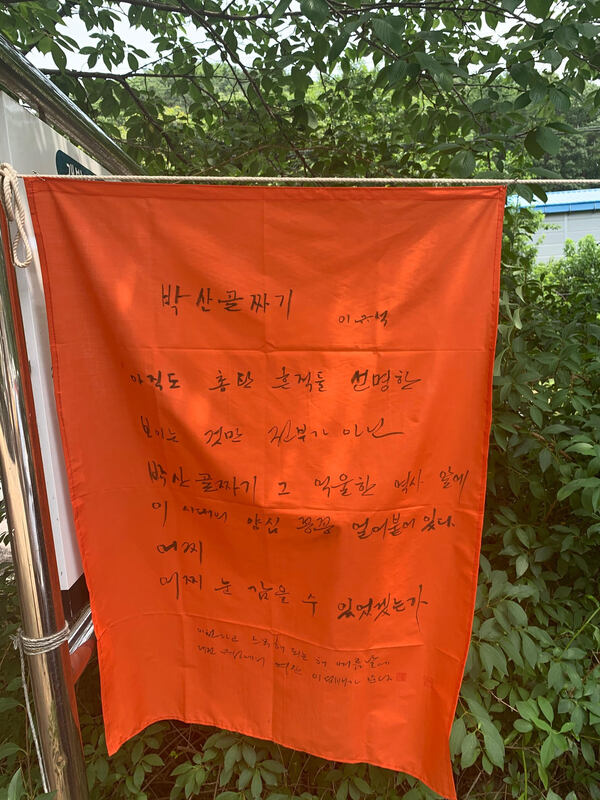

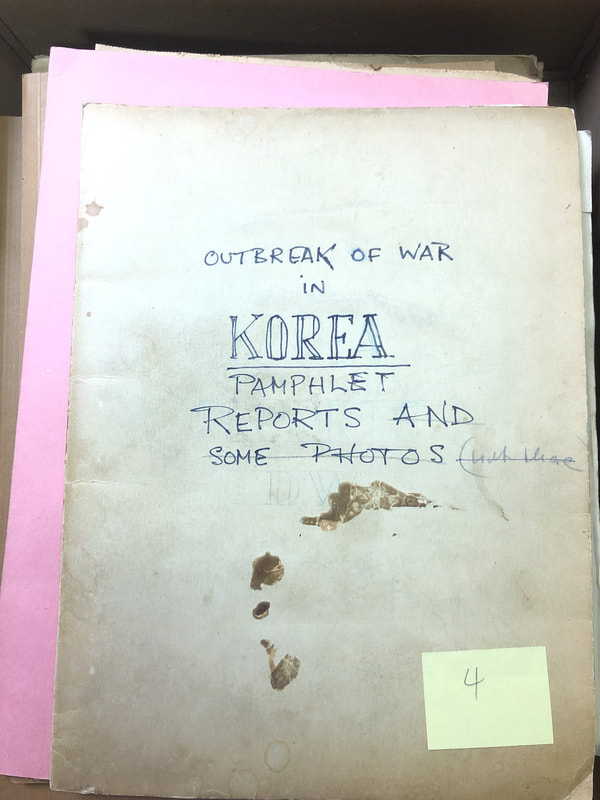

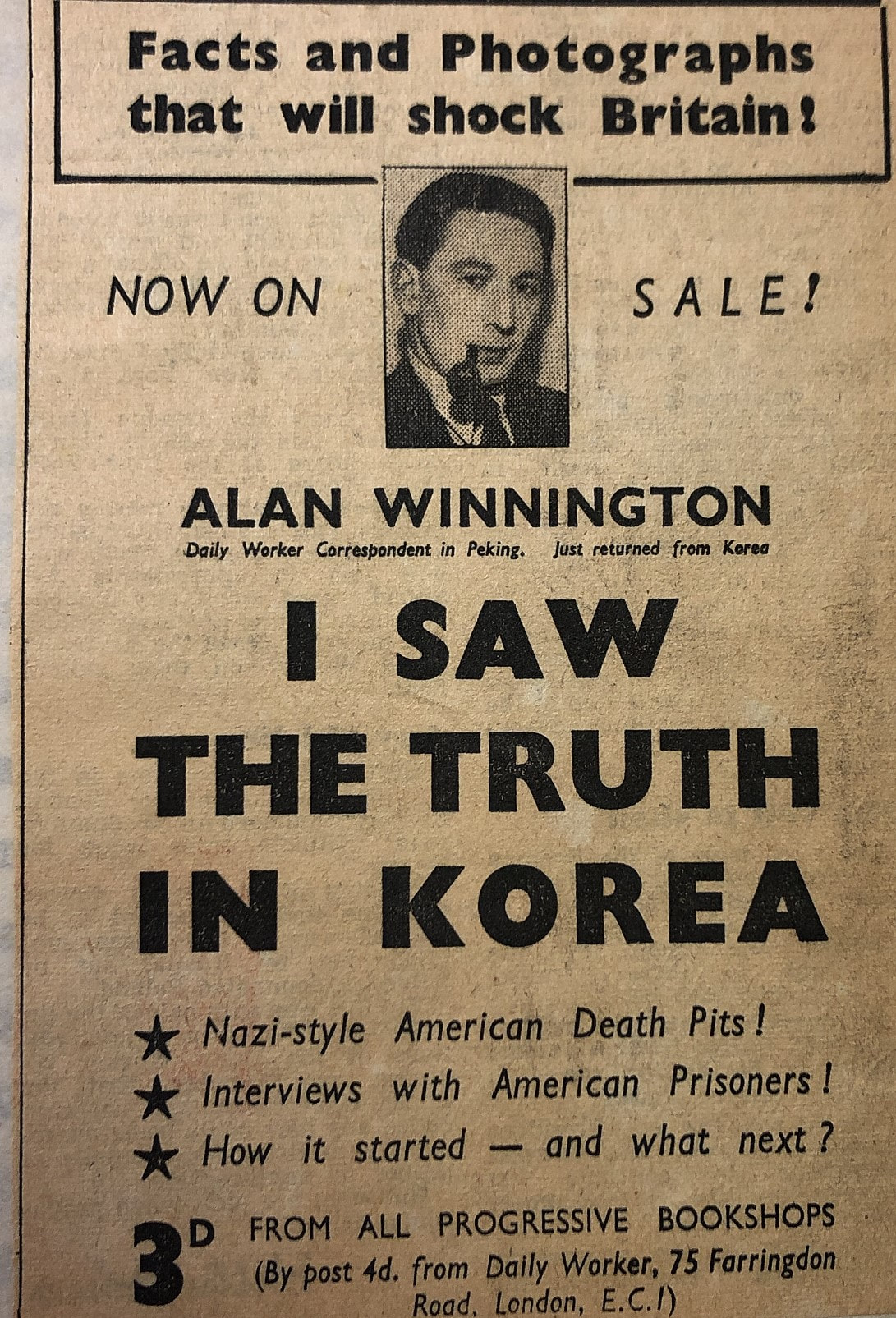

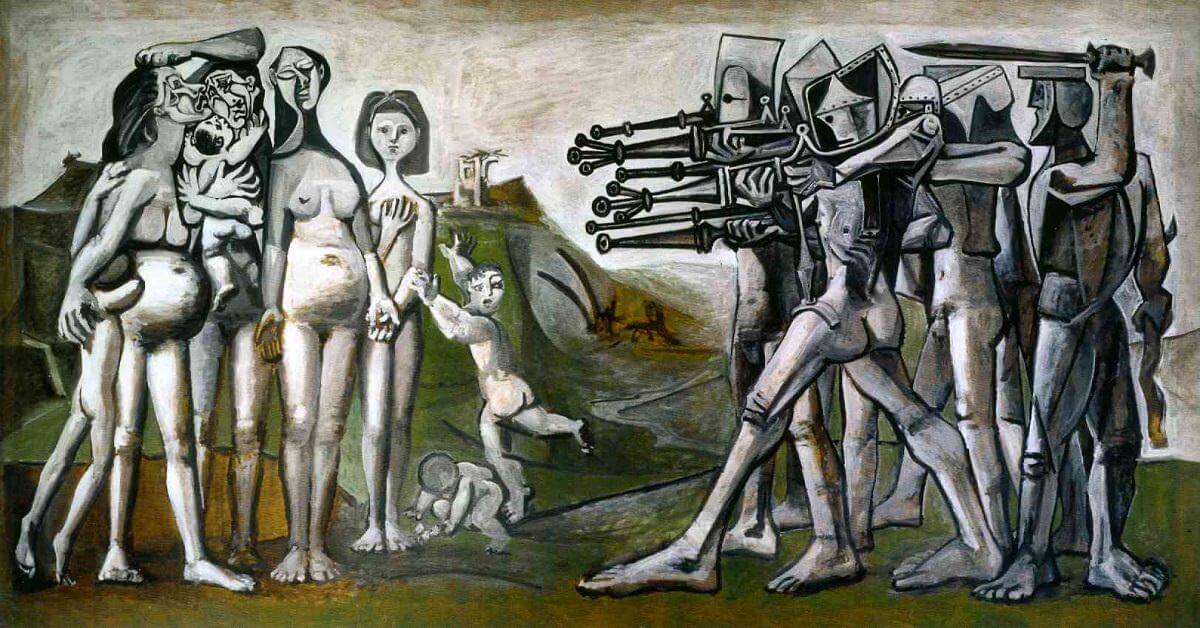

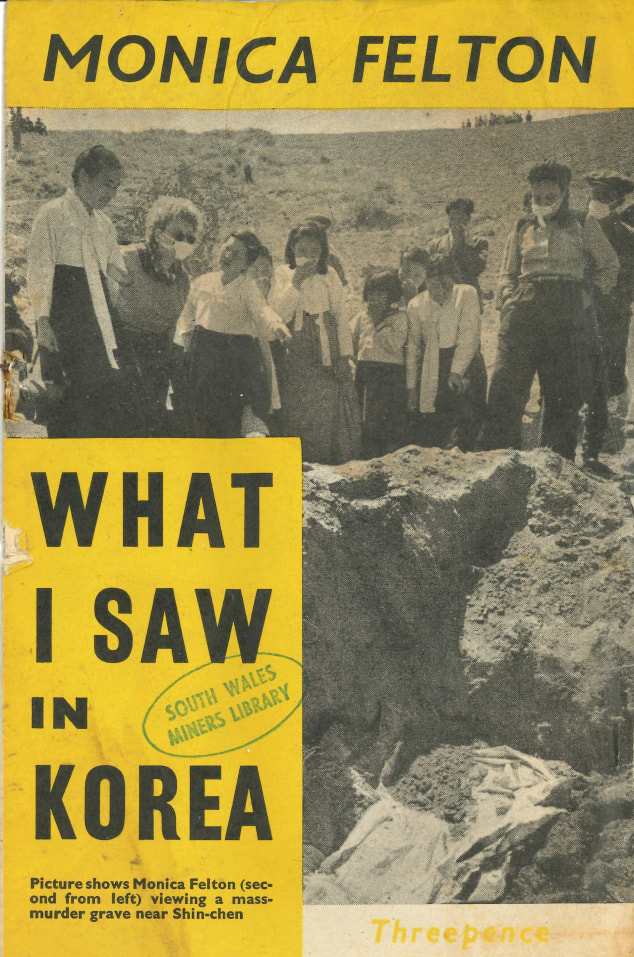

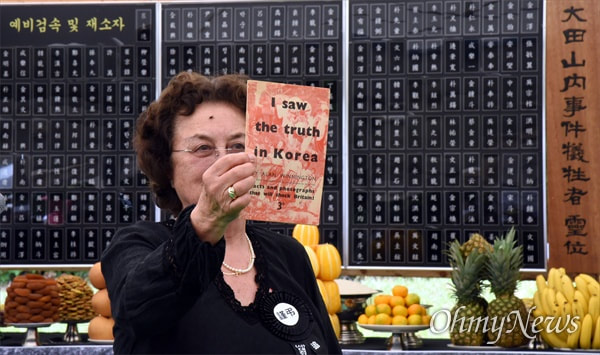

There is much to be written - and there will be shortly on this site - about the poet Jeon Sukja for whom poetry is a form of catharsis, or an extremely private and confessional way of dealing with what happened to her Father. Her story reveals one of these "untranslatable" experiences, and to see it written down and performed (always saturated with the pain of these memories) provides us with a unique and moving record of what continued to happen at this place long after fighting in the Korean War came to an end. But there are also many public expressions of poetry here initiated by the Daejeon Writers Group who I was extremely privileged to accompany to a conference on the Jeju 4.3 incident a couple of years ago. At this time of year the whole valley is usually covered in poetry banners in different colours, expressing what this history means to these writers and how it connects to other more recent historical events in South Korea. At Saturday's memorial I met the poet Park Soyoung for the second time who gave me a reading of her poem. I took my picture with her and talked about future collaborations with poets in the UK because of the Winnington connection. I hope that something meaningful can be arranged in the future.  Last years symposium on the Daejeon Massacre. Last years symposium on the Daejeon Massacre. Over the next couple of years I will be working for the local government in Daejeon in order to research the Daejeon Massacre before the building of a Peace Park here in 2024. Given the current state of the global pandemic this is proving more difficult than expected, but the goal is to have an International Conference in Daejeon at the end of this year, as well as a variety of other events that I aim to remind people of sporadically. Please get in touch if you would like to contact me about Winnington or the site in Daejeon where new information is emerging on an almost daily basis. The following posts are my first attempt to explain the work I have become involved in in South Korea. This is a project I have been part of for over three years now, but it is only at this point that I feel confident enough to speak of it as someone who knows “the facts”. As the constantly-reoccurring Tory government in the UK makes the possibility of an eventual home-coming increasingly unlikely it is about time I threw my full energy and commitment towards exploring and uncovering the reality of what happened here. Over the last few years my hometown has been Daejeon, South Korea. Whilst living here I have become heavily involved in truth-seeking work at a place where it is said 7,000 people were murdered by their own government with American supervision at the beginning of the Korean War in 1950. I will explain more about this in my next post, but for now it should be understood that this is an absolutely devastating event in Korean history that it is almost impossible to explain the gravity of to those on the outside. There are few historical parallels that can be adequately talked about in the west outside of World War Two anyway. The historian Bruce Cumings has rightly pointed to how little is known about this massacre when compared to something like Screbrinica in Bosnia. But as someone living in the vicinity it has been my goal over the past three years to find out everything I can. This is because I am adamant that it concerns not just Korea but the entire world. These tragedies result from the same mendacity by politicians, from the same warmongering and apathy, wherever they take place. That is why the more that is found out here - and we still know very little - the more I am drawn into the difficult process of discovering the truth. Let’s start with what facts there are. These are curious for me because they are at once local and global in affect. What happened here was witnessed by the English journalist Alan Winnington in his pamphlet “I Saw The Truth in Korea”. The shock waves accompanying this history extend way beyond what is immediately visible at this one place.In our recent film on this subject at Ahim Media this is clearly visible. It is a story with no closure, an attempt at truth telling shrouded in propaganda from both sides. This is because Alan’s account was dismissed as an untrustworthy source. He was exiled from the UK for fourteen years and accused of “treason”. His sincere attempt at journalism struck from the record he lived the rest of his life in East Berlin. But his pamphlet has remained for the last seventy years successfully interred in antique left wing bookshops. It’s value not in the words on the page, but a kind of ‘Communist kitsch” torn from context and unaware of the pain still existing half way across the world. But this is no longer the case. Alan has has now been front page news in South Korea thanks to the joint efforts of our organization Ahim and the journalist Im Hyoin. What is important to understand is that Alan’s report is merely the tip of the iceberg. Monica Felton - councillor for West Pancras in London and a tireless campaigner for feminism and peace during the war - was another person on the left who tried to report on massacres at Sincheon in the North. This is the place that inspired Picasso to paint an extremely powerful picture around the same time (maybe he'd been reading Alan and Monica’s reports)! But she was also investigated by the UK authorities, expelled from the Labour Party and fired from the council, with phony charges of “treason” applied to her reporting much as it was with Winnington. Her pamphlet and book “Why I Went” is similar to Alan’s. Available in the same bookshops, divorced from the reality that has always existed on the ground in Korea. For various reasons this censorship was particularly noticeable in the UK and much of it is covered in great detail within Ian McLaine's text "A Korean Conflict: The Tensions Between Britain and America" (2016). What is clear is that Winnington’s pamphlet was something that worried the state so much even mildly critical accounts of what was happening began to be censored in its wake. Apart from Monica Felton's later pamphlet, one of these instances concerns the famous UK journalist James Cameron, who wrote articles on the outbreak of war in Korea for the Picture Post. In a special edition Cameron and a photographer called Bert Hardy attempted to publish an article called “An Appeal to the UN” with images and text carefully arranged to favour neither side in the conflict. There were pictures of prisoners in Busan being treated terribly, but there were also pictures like this one of American troops in the North made to parade around dressed like Hitler with Stars and Stripes trailing behind them. In his autobiography Cameron talks about the care with which he had written and edited this article before it was published, as well as the ways in which he tried to strip it of all emotion and just present the ‘facts’: “Finally we agreed on a layout which in the circumstances was the most tactful and unsensational possible. We used only those pictures of the prisoners which would establish their dire condition without unnecessary shock; my article was written and re-written over and over again until it became almost bleak in its austerity” The Times and The Telegraph newspaper in England had already written similar articles on the Korean War at this time. Even the conservative papers in the UK were critical of the brutality with which prisoners were being treated. ‘My article amounted to a vigorous plea that if our ally Dr Synghman Rhee saw fit to use methods of totalitarian oppression and cruelty’, Cameron explains in his autobiography, ‘it should not be done under a UN flag”. This issue of the Picture Post was never printed. The press was turned off before it could reach the public. It’s editor – Tom Hopkinson – had to leave the magazine after its Conservative owner Sir Edward Hulton feared he would be breaking the law. These pictures and opinion pieces were never actually published at all. Even though they are often used in discussions of the Korean War they are torn from any context and people seem largely unaware of their origin. The only reason they even exist today is once again because of the Daily Worker who leaked some of the pictures and published them under the headline “KOREA EXPOSURE SUPPRESSED – PICTURE POST EDITOR SACKED”. The Picture Post was eventually taken out of circulation in England completely. It became a shadow of its former self, desperate to avoid any hint if opprobrium from the state. These images on the road to Gongju were also included in the suppressed version: The picture above was one of a series quickly snapped by an Australian photographer as he passed by the scene at the beginning of the war. It's power rests in how it captures a moment that otherwise would be lost in time. Photographs like these speak a truth that needs no accompanying words and it is easy to see why the decision was made never to print them. In 2008 The Truth and Reconciliation Commission of South Korea used the photo above and witness accounts to find the exact place in which these people were so cruelly slaughtered. In South Korea there are likely many places like this that have since disappeared under apartment blocks, or simply have no living witnesses able to reconstruct the story of what went on. This doesn't even take into account the terror with which any surviving family members were subjected to under successive dictatorships. For a bold and compassionate look at this see Hwang Sukyoung's text "Korea's Grevious War" (2016). It is important to know that these events did not exist in isolation and were deliberately suppressed. They were part of a series of state sanctioned killings - often referred to as the Bodo League Massacres - that took place all over Korea at the beginning of the war. These massacres peaked thanks to the brutality of the first South Korean President Synghman Rhee, but continued in a wave of revenge killings and cycles of violence until the end of the war. The Korean War may have ended in a stalemate, but the civilian toll suggests the complete opposite of a draw. From the killing of suspected communist prisoners at the beginning of the war, to the awful treatment of North Koreans after the Incheon Landings, the eventual death toll of civilians is 2,730,000 even when relying on the most conservative estimates. This includes deliberate strafing of refugee columns by aircraft, the endless bombing of cities, as well as the senseless massacres already covered above. That is why I was so glad to find an archive of Alan Winnington’s notes and journals at Sheffield University earlier this year with the help of his eldest son Joe. Thanks to the mayor of Daejeon - Hwang In Ho’s - letter, we were able to visit and find some incredible primary sources about what happened at this time. The archive is still uncatalogued, so it was incredibly generous of the person in charge (Chris Loftus) to allow us access. The Winnington archive - from my own experience - will be able to provide much needed information that either refutes or backs up both first hand accounts and official versions of the narrative around these civilian deaths. Further to this on the seventieth anniversary of the Korean War critically evaluating these sources has the potential to genuinely contribute to research that will inform the curation of information and exhibitions in a peace park that will be built on the site that Winnington visited in 2023. This is why the search for truth is so necessary, even when on the ground in Daejeon it seems long overdue. The word repeated by those in charge of the museum project is an English one: "healing". All information can only add to this important goal. I will be visiting Sheffield regularly in the future and hope even more of interest can be discovered. Read these three articles by the journalist Im Hyoin (In Korean) if you want to get a sense of our trip, including an excursion to Cable Street and Marx’s Grave at Highgate (both places associated with the beginning and end of the political journey of Winnington himself): http://www.joongdo.co.kr/main/view.php?key=20191118010007506&fbclid=IwAR3ApkfAXayJWEXOwRbu7LWLXObHWzSHrltprWBjkKSbpY-aSapRVmJTWro http://www.joongdo.co.kr/main/view.php?key=20191119010008052&fbclid=IwAR16wtt_K-uY2uwrtEoNv4Qh5g42LKD97KGjGluYLKfs7o9bp0fHdvZjQWo http://www.joongdo.co.kr/main/view.php?key=20191124010010053&fbclid=IwAR09z6ZwdWFEM_nT2FuDiNsg1mGaDaatGZkyYKQuA3pihqTCZhRcGs6qIAQ In 2019 our production company Ahim Media (with the help of the donations from Daejeon citizens) invited the widow of Alan Winnington (Esther Samson) to South Korea. In all of the posts that follow I think nothing speaks with more wisdom, conviction and clarity than the words of Esther herself who gave a short speech at the memorial where she held aloft Alan’s pamphlet (the subject of my next post) in a gesture of defiance that moved me greatly. It is to the Bereaved Families Association of Daejeon, Esther, her son Joe, and Alan's grandsons Thomas and Jonathon to whom I dedicate these series of posts on Korea. As time passes I am confident we will find out much more together. A MEMORY OF ALAN WINNINGTON

I first met Alan in Beijing in 1949 when he was a foreign correspondent covering the civil war in China for his English Newspaper. I was his interpreter and assistant. When the Korean war broke out in June 1950 he was sent by his paper to cover a war that he thought would be over in weeks. He stayed until in the end of the war in 1953 and on one of his rare visits back to recuperate from the dreadful conditions in Korea, we married. He witnessed unspeakable horrors - indiscriminate bombing of innocent civilians, and the use of napalm dropped on the population. Alan described a five year old boy, his face and body horribly burnt, with no eyelids and his weeping mother saying “who will marry him”? not realizing her son would not survive. It affected Alan for the rest of his life and he could never get over the pain and misery he saw because of the war. But the most horrifying description was when he visited the mass grave in Rangwul near Daejeon of thousands of intellectuals slaughtered by the authorities with bodies barely covered with soil. He wrote a pamphlet likening it to the Nazi slaughter in the concentration camps. His report of what he witnessed was suppressed by the warring parties and Alan was branded a traitor by the British Government, his passport confiscated and if he returned to Britain he would of faced charges of treason. Not a single British or American journalist paid a visit to Rangwul to investigate and Alan was exiled from his country for twenty years for exposing the truth. He died in 1983 too late to realize his sacrifices for exposing the crimes against humanity had not been in vain and acknowledged by those thousands of intellectuals massacred by the warmongers. Esther 27/06/2019 In the first half of 2018 I was privileged to be involved in The Longest Tomb, the first documentary on a politicide in Daejeon aided and abetted by the US military in 1950. We took the film to SOAS with Mr Lee and Ms Jeon at the end of May this year. Ms Jeon read two poems, which I then explained to the audience. There was also a lively discussion at the end of the event. I truly hope I can find a copy of Ms Jeon's reading to put on this site. I will add a link to this post if one emerges. In the meantime please watch the above film, another version of which we hope to premiere in the US (Washington DC) in 2019.  Ms Jeon reads from her poem "A Wood Pigeon On The Pylon" Ms Jeon reads from her poem "A Wood Pigeon On The Pylon" There is one review of the event on Tongil news in Korea (In Korean, obviously). Click the following link: http://www.tongilnews.com/news/articleView.html?idxno=125044 There is also a similar review of the Korean premiere here: http://www.joongdo.co.kr/main/view.php?key=20180519010007868 |

Categories

All

Archives

April 2023

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed